One hundred years ago, it became illegal to stop off at the corner bar for a beer – the Volstead Act, commonly called Prohibition, outlawed the production, importation, transportation, and sale of alcoholic beverages in the United States.

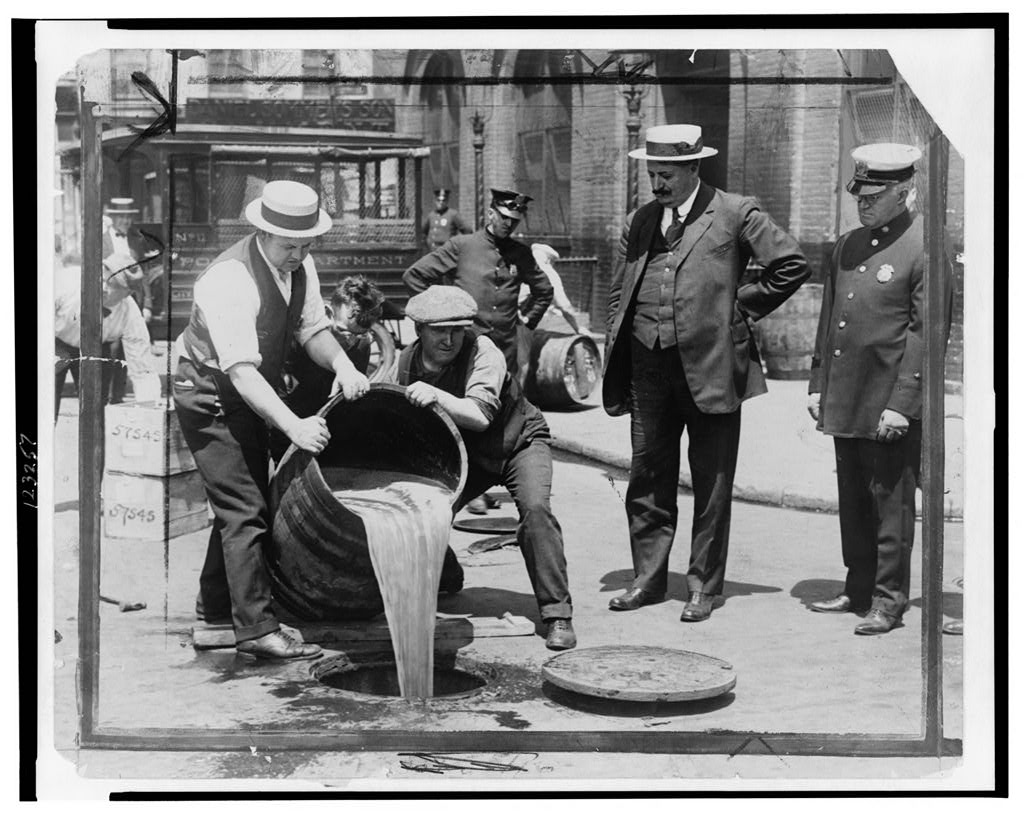

Courtesy of the Library of Congress, LC-USZ62-123257 Commissioner John A. Leach, right, watching agents pour liquor into sewer following a raid during the height of prohibition

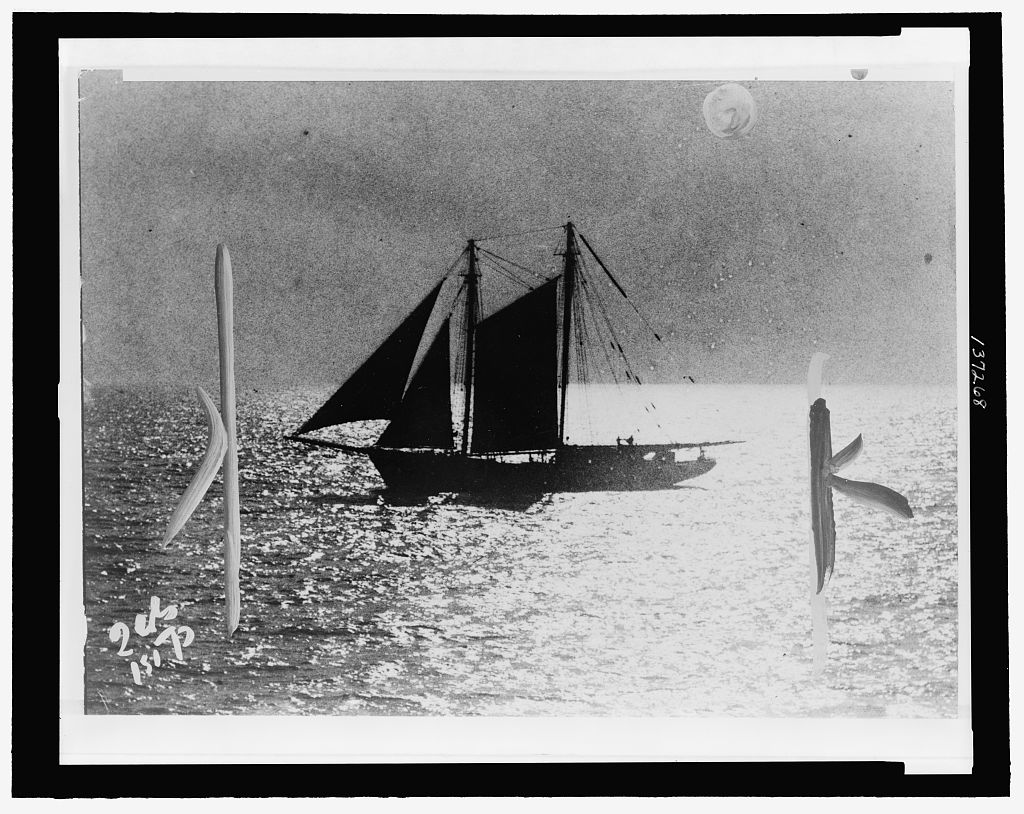

Of course, the desire for alcoholic beverages didn’t disappear simply because it was illegal. Organized crime began working with rum-runners, attempting to smuggle alcohol into the United States. The ships carrying the liquor would drop anchor close to the coast, communicate with their contacts on land, and off-load their contents to be dispersed to speakeasies (illegal drinking establishments) ashore.

Since open communication would make it easy for law enforcement to intercept these illegal deliveries, the rum-runners used codes that they thought would make their communications secure.

Courtesy of Library of Congress LC-USZ62-137268 One of the run[sic] runners of the night and its nemesis

Enter Elizebeth Smith Friedman.

Mrs. Friedman was the chief cryptanalyst for the U.S. Navy, and then the Coast Guard. In her, the smugglers’ codes met their match. She was surprised that the alcohol smugglers used simple encryptions, and she and an aide solve hundreds of messages in a couple months.

Often a keyword was associated with the subject matter of the message, which made it simpler to solve. In her memoir, Mrs. Friedman commented that “when choosing a key word, never choose one which is associated with the project with which one is engaged.” The codes became harder and more varied, but Mrs. Friedman and her aide kept solving them.

Elizebeth S. Friedman Departs from Washington for the South, to Appear in Federal Court George C. Marshall Foundation photo

While testifying against Al Capone’s liquor smuggling ring in New Orleans, Mrs. Friedman taught a lesson on the science of codebreaking and the use of mono-alphabetic ciphers right in the courtroom. Col. Amos Woodcock, director of the Bureau of Prohibition said that without the work of the cryptanalysis unit and the expert testimony of Mrs. Friedman, the case would not have been won.

Elizebeth S. Friedman working at a desk George C. Marshall Foundation photo

Mrs. Friedman and her aide solved more than 12,000 coded messages for the Coast Guard between 1928 and 1930, preventing delivery of huge amounts of illegal alcohol. They also solved messages for other government organizations, as Mrs. Friedman’s cryptanalysis unit was the only non-military codebreaking unit in the federal government.

Notes:

Elizabeth Friedman memoirs. Digital reproduction of original manuscript. 1966. Elizebeth Smith Friedman collection. George C. Marshall Foundation.

Also referenced: The Codebreakers by David Kahn