- She wrote the book on code breaking for the U.S. Army, and taught the first cryptography classes to soldiers in WWI.

- In three months, she decrypted two years of backlogged Coast Guard messages, using only a pencil and paper.

- She was the only woman employed by the Coast Guard at the time.

- She served as an expert witness at several high-profile Prohibition trials.

- She created the Coast Guard’s first code-breaking office.

- She also created the first code-breaking unit for the OSS.

- She decrypted letters from a suspected spy for the U.S. Post Office.

- She decoded communications from Nazi spies in the Western Hemisphere, and the information was used by the FBI to arrest spies.

- She and her team broke the Enigma code machine, unaware that anyone else was working on it.

- And she never talked about any of it, because she knew she couldn’t. She worked in the shadows, and her great accomplishments remained classified and unknown for a long time.

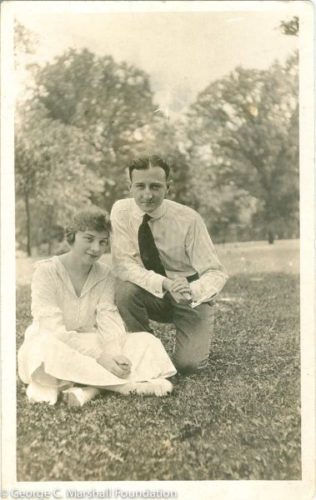

Elizebeth at Riverbank

Meet Elizebeth Smith Friedman, college-educated Midwestern girl, who in 1916 went to work for an eccentric man with a team trying to locate Baconian ciphers in Shakespeare’s writings at Riverbank Laboratories in Illinois. She couldn’t find any ciphers, but she became interested in codes; how to create them, and how to decipher them.

William and Elizebeth at Riverbank, while inventing code breaking.

She found a partner in life and cryptography in William Friedman, and with their team they deciphered all federal encrypted information for eight months prior to the United States entering World War I. The two developed the instruction of soldiers in the art of code writing and code breaking by learning for themselves in the evening and writing the next day’s lesson.

Elizebeth with daughter, Barbara, and son, John.

After the war, Elizebeth settled down to be a wife and mother, but her expertise was too valuable to the government. In 1923, she went to work for the U.S. Navy decrypting codes. This work led Elizebeth to decoding the communications of rum runners for the U.S. Coast Guard full time during Prohibition; the only woman employed by the Coast Guard at the time. She decoded 12,000 messages in three years, and her testimony sent 35 bootlegger bosses to prison in 1933.

Elizebeth leaving to testify against bootleggers.

Elizebeth later assisted Canadian officials in the arrest of opium smugglers, and helped the U.S. Post Office catch a Nazi spy in New York City.

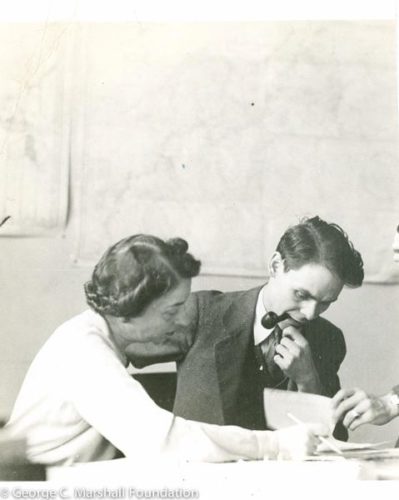

Elizebeth and a member of her team working out a code solution.

During World War II, Elizebeth and her small team of code breakers worked for the Navy, and were primarily responsible for the identification of Nazi spies and their sympathizers in South America. Credit for their work, which included solving three different Enigma machines, was purloined by J. Edgar Hoover, who claimed his FBI agents were responsible.

Elizebeth solving code with paper and pencil.

At the time that Elizebeth and her team were working to break the Enigma codes, she didn’t realize anyone else was working on the Enigma.

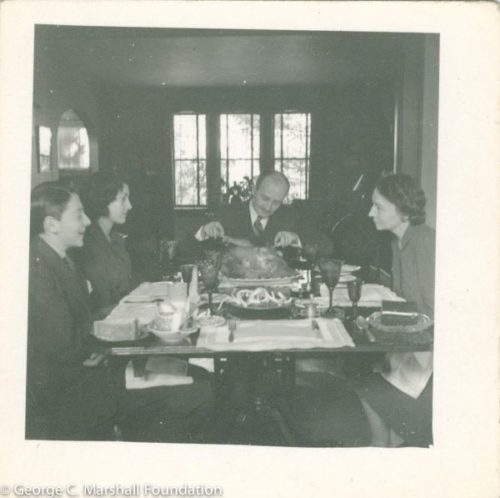

The Friedman enjoying a holiday dinner in the early 1940s.

Many are familiar with the work of Alan Turing and Bletchley Park, but do not know that as a primary codebreaker for the U.S. Army, Elizebeth’s husband, William, was doing the exact same thing with his large team at Arlington Hall. They came home from work each evening, and talked over dinner together without knowing what projects the other was working on. The Secrecy Act did not permit them to discuss work, even though they were doing the same job for different branches of the U.S. military.

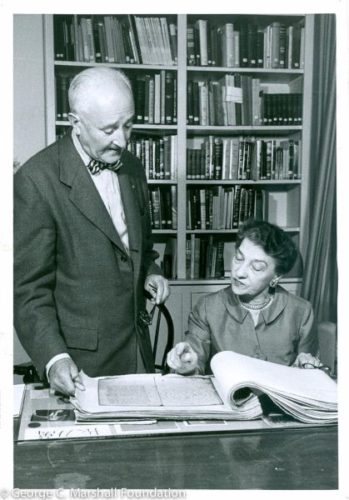

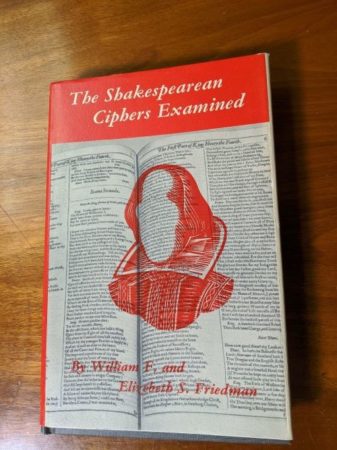

William and Elizebeth working on disproving the presence of ciphers in Shakespeare.

At the end of the war, Elizebeth was told that her skills were no longer needed, and so she and William returned to the project that first brought them together – working to prove there were not any Baconian ciphers in Shakespeare. This led to the publication of their book, The Shakespearean Ciphers Examined.

William and Elizebeth’s book

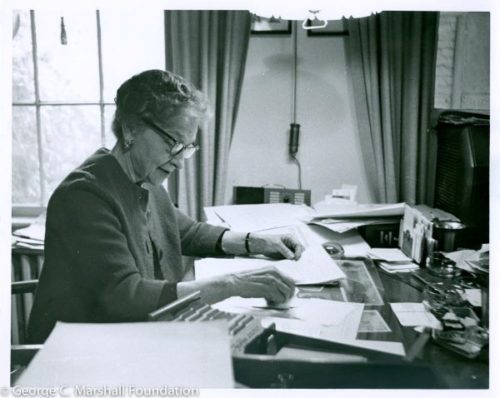

In their retirement years, William and Elizebeth decided that their personal library and papers would not go to the federal government, but to a small library that would make them available to researchers. They started working on readying their collection together, and after William’s death, Elizebeth worked tirelessly on their collection’s donation to the George C. Marshall Foundation. Elizebeth followed the truck carrying their collection from their home on Capitol Hill to Lexington, Virginia, and spent many days getting the collection organized in its new home.

Elizebeth working on the organization of the Friedmans’ personal collection in preparation for donation.

The William and Elizebeth Smith Friedman collections are available to researchers, and portions have been digitized.

For those who are interested in learning more about Elizebeth, visit her Marshall Foundation Library collection.

Elizebeth in front of her painting

The painting at the George C. Marshall Foundation

Notes:

Photos from the William F. Friedman and Elizebeth Smith Friedman collections.

Melissa has been at GCMF since Fall 2019, and previously was an academic librarian specializing in history. She and her husband, John, have three grown children, and live in Rockbridge County with three large rescue dogs. Keep up with her @life_melissas.