Today is National POW/MIA day, honoring prisoners of war and those still missing in action.

I wore an MIA/POW bracelet for years. The name on my bracelet was Capt. John N. Flanigan, USMC. I only knew the information on the bracelet; that Flanigan was from Florida, and he disappeared Aug. 19, 1969 over North Vietnam.

MIA/POW bracelet for Capt. John N. Flanigan

I wrote to the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency, and they sent me an information sheet. I discovered that Flanigan was the Radar Intercept Officer in an F-4 “Phantom.” The pilot was Lt. Col. Robert Smith. The plane, flying out of Da Nang, disappeared on a photo reconnaissance escort mission over North Vietnam. There was no more information.

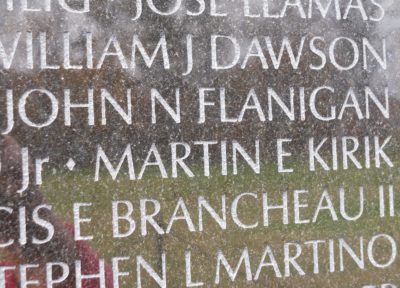

I wore my bracelet in remembrance every day for many years. When I had the opportunity, I visited the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, D.C., and found Flanigan’s name. I wished that I could find his family and tell them that I still remembered.

John N. Flanigan on the Vietnam Veteran’s Memorial in Washington, D.C. Panel W 19, Line 67

In 1995, the United States normalized relations with Vietnam. One evening that summer, I was sitting on the sofa at our house in Kansas as the news went off. The show Eye to Eye with Connie Chung came on — a show I’d never seen before (or since). Our old TV had a channel-changer knob, no remote, and I was too tired to walk across the room to turn it off.

I zoned out through the show until I heard that CBS news reporter Bill Plante and his wife, Robin, were traveling to Vietnam to learn more about her father’s disappearance. They began talking about Lt. Col. Smith, pilot of an F-4, whose RIO was named Flanigan. I jumped up off the sofa hollering “Oh my gosh! Oh my gosh! Oh my gosh!” After the broadcast, I wrote to the show, which forwarded my letter to Mrs. Plante, who forwarded my letter to Capt. Flanigan’s daughter, Audrey — who lived in the same town as my in-laws.

The next time we were visiting family, I went to meet Audrey and learned about her father. Flanigan had been a champion water-skier as a young man and had worked in an acrobatic water-skiing show at Cypress Gardens in Winter Haven, FL, as a teenager. He skiied in the Esther Williams movie Easy to Love (as did Martha, who would be Flanigan’s wife). He enlisted in the Marines as a clerk typist right after graduating from Winter Haven High School in 1952, during the Korean War. He soon trained to be a navigator, and flew in the Fairchild 119, which the Marines called the R4Q-2 and whose nickname is the “Flying Boxcar” for its ability to haul cargo.

Fairchild 119, known to Marines as the R4Q-2

Flanigan was enlisted for 9 years before he was commissioned in 1961. He served in the Florida Keys during the Cuban Missile Crisis, and overseas in Lebanon and Dominican Republic. Flanigan transitioned into the McDonnell Douglas F-4 “Phantom” as a radar intercept officer and flew his first tour in Vietnam in 1965-66.

Lt. John N. Flanigan in 1968, just before he was promoted to captain.

While in Vietnam, he also trained radar intercept officers, and continued to train them when he returned home to Naval Air Station Glynco in Georgia. He made captain in 1968, and his second tour in Vietnam began in April 1969 with VMFA 542, the Tigers, flying as RIO for Lt. Col. Smith. Flanigan was the senior RIO there, with several thousand hours of flight time.

Capt. Flanigan in the back seat of an F-4 “Phantom.” Unknown pilot.

On Aug. 19, Smith and Flanigan in their F-4 “Pigment 50-2” took off from Da Nang as photo reconnaissance escort to an area near Phu Thuy, Quang Binh, (then North) Vietnam. Smith made one run over the target, but never rendezvoused with the reconnaissance plane for a second run. Search and rescue operations continued for three weeks, but the plane, Lt. Col. Smith, or Capt. Flanigan were not found. Martha Flanigan received a telegram: “I deeply regret to confirm that your husband became missing in action … On behalf of the United States Marine Corps I extend our sincere sympathy.” Flanigan left behind Martha; two daughters – Audrey and Cynthia; and a son Russell, along with extended family and friends who had questions for many years.

Flanigan family, Easter 1967. John and Martha Flanigan, and Russell, Audrey and Cynthia.

Those questions began to be answered 20 years later in 1989, when remains believed to belong to Capt. Flanigan were repatriated. It wasn’t until the mid-1990s that mitochondrial DNA testing was available to positively identify Capt. Flanigan, and he was returned home to Florida. The family set a late summer date for an internment in the the cemetery in his home of Winter Haven, FL, and Audrey invited me to attend along with others who had worn her father’s bracelet for so long and had been in touch with his family. I was in Kansas, eight months pregnant, and the doctor wouldn’t let me travel even though I begged to go.

In August, 1997, I took off my bracelet and put it away in my jewelry box. After 28 years, Capt. Flanigan had finally come home.

I am grateful to Audrey Lowrey-Hall for her friendship over the years; for allowing me to tell “our” story, for answering my questions, and for use of her photos in this blog.

Some information came from the Library of Congress Vietnam-Era Prisoner-Of-War/Missing-In-Action Database

Photo of the Fairchild 119 is courtesy of William T. Larkins.

Melissa has been at GCMF since Fall 2019, and previously was an academic librarian specializing in history. She and her husband, John, have three grown children, and live in Rockbridge County with their large rescue dogs. Keep up with her @MelissasLibrary