When John Hermansen was born in the early 1900s in Pennsylvania, he could have never known that he would travel and traverse continents in his lifetime. No one of his generation foresaw what turned out to be the deadliest war in mankind’s history. But the Greatest Generation did what people have always done; they overcame. They survived. They persevered.

One of the ways these warriors stayed strong was by remembering what they were fighting to protect. They kept pictures literally close to their hearts, and letters in their helmets. These momentary glimpses back home were steady reminders of what they were defending with their very lives.

As an intern here at the George C. Marshall Foundation, I have the privilege of assisting the librarian by organizing, cataloging, and preserving these cherished pieces of history. Although I have always been interested in history, holding these letters in my own hands have made these people real to me. In working at the Foundation, I have enjoyed plenty of wartime love letters; and mourned those letters with sad words informing someone of a lost loved one. By far, I prefer romantic letters, especially those written between John Hermansen serving in Greece and his wife Lois, back home in Pennsylvania.

John and Lois Hermansen in 1946; both had served in World War II.

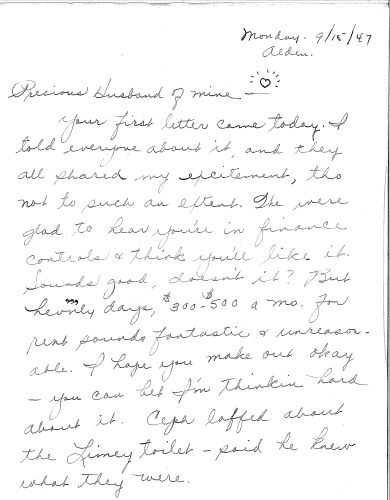

As Shakespeare wrote, “A rose by any other name would smell as sweet.” John and Lois certainly believed these words. As they wrote numerous letters to each other across the Atlantic, they hardly used the same term of endearment twice. At the end of the war, he was assigned to work in Greece as part the effort to stabilize war-torn Europe. Lois was not able to join him for several years, and so their letters were all they had of each other. I am sure the endearments they used made the other smile. Some of them are classics, such as “Darling,” “My Dearest,” or “Honey” others were timelier, like “Bright Eyes,” “Honey lo,” and “Angel-Mine”. They both waxed rather poetic as time went on. Lois calls John “Precious Husband of Mine” complete with a small heart drawn beside it.

Lois’ address to her husband

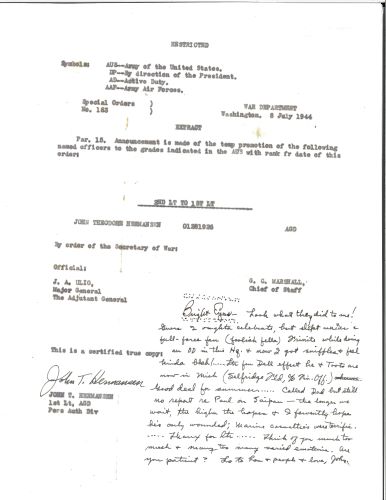

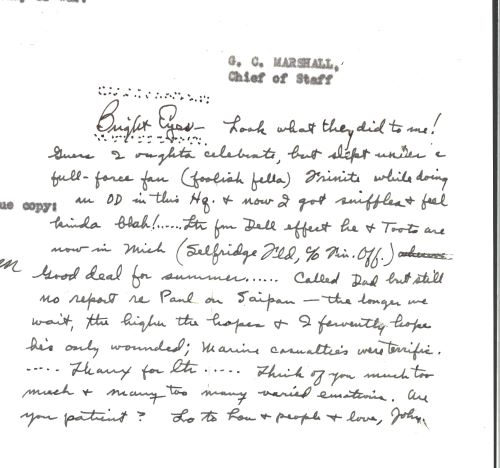

In dozens of letters, they used over twenty different phrases to greet and convey their love for the other. John wrote to her ecstatically after he was promoted from second Lieutenant to first Lieutenant. He wrote directly on the orders from Marshall’s office, not even bothering to find another piece of paper.

Orders advancing John to first lieutenant

The note John wrote to his wife on the orders

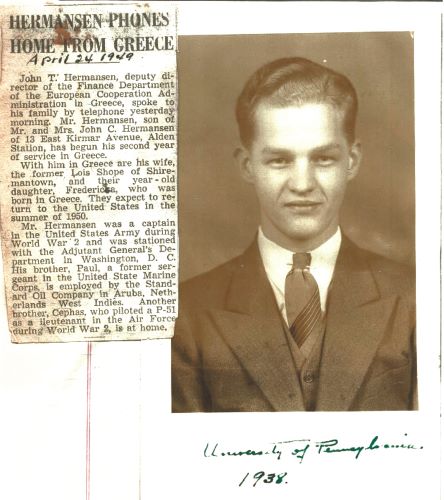

Not all the correspondence was between the lovers. John wrote often to his parents, and they wrote back just as often. His father wrote of the goings on in their small town, and how his mother was doing. It is clear the respect and love that was had between the two men. In fact, John made the local newspaper when he called home from Greece.

Newspaper account of an overseas phone call

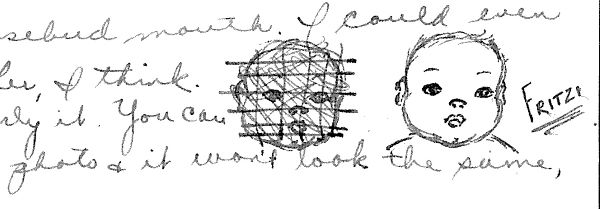

When Lois was finally able to join John in Greece in the fall of 1947, they started a family. Lois wrote to her family and her in-laws of their children, and life in Greece. She drew a small picture of one of their children, whom she referred to as “Fritzi”. In the same letter she mentions that she cannot wait for Fritzi to meet the grandparents.

Lois’ drawing of Baby Fritzi

John and Lois’ son Jack Hermansen was so very generous in donating his family’s letters and genealogy to the Foundation. I am thoroughly enjoying going through the letters and learning more about the history in these letters and papers. I am sure that researchers will find these writings invaluable in the future.

Eryn Davis is a library science graduate student and an intern at the George C. Marshall Foundation this summer. Her mother raised Eryn on World War II history and Big Band music.