Pilot James Stewart and the B-24

"Somebody sure could get hurt in one of these damned things"

James Stewart loved airplanes. As a young boy, he saved money from his paper route to ride in a biplane, after spending weeks convincing his mother it was safe. After graduating from Princeton, he took flying lessons, and got both his private and commercial licenses. He bought a Stinson 105 to boost his flying hours, and because he knew it was the model the Army Air Corps were using to train pilots. He was sure the United States was going to get into the war in Europe, and he wanted to continue the family legacy of serving in the Army by flying.

Lana Turner and Jimmy Stewart in Ziegfield Girl (public domain)

Stewart, better known as Jimmy, was wrapping up production of Ziegfield Girl – in which he starred with an ensemble cast including Lana Turner, Judy Garland, and Hedy Lamarr – when he enlisted in the Air Corps as a private. He spent nine months training at Moffett Field, CA, where he studied for and passed the exam to be commissioned. His 400 hours of flying time got him into the cadet program, but not without a fight. Stewart was in his 30s; most military pilots were in their early 20s. He was also underweight.

Jimmy Stewart being inducted to the Army Air Corps. (Warfare History Network photo)

Stewart spent nearly a year as a training pilot teaching in the AT-6, AT-9, and the B-17. In Feb. 1942, he had to present the 1941 Oscar for best actor, since he had won in 1940 for The Philadelphia Story. He wore his uniform sporting his pilot’s wings, and accompanied Ginger Rogers to the ceremony.

Ginger Rogers and Lt. Jimmy Stewart at the Academy Awards, 1942. (Jimmy Stewart Museum photo)

He didn’t want to spend the war as a training pilot, but the Air Forces were leery about sending a well-known actor into danger. Stewart finally got his way, and deployed to England in the fall of 1943, as the commanding officer of the 703rd Bomb Squadron, 445th Bomb Group, flying the B-24 “Liberator,” a four-engine heavy bomber.

B-24 Liberator (Lockheed Martin photo)

The B-24 was a bear to fly and showed poorly at low speeds, but it had a longer range and greater bomb capacity than the B-17, and was the most-produced airplane of World War II; there were approximately 6,000 more B-24s built than B-17s. Stewart said of the plane, “In combat, the airplane was no match for the B-17 as a formation bomber above 25,000 feet, but from 12,000 to 18,000 it did a fine job.”

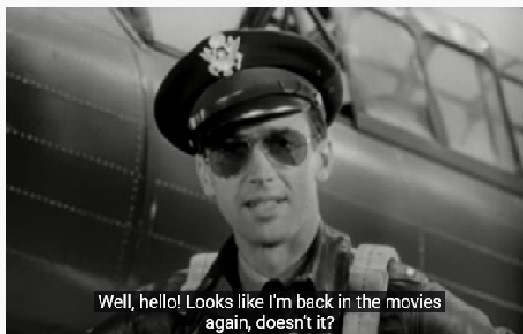

Capt. Jimmy Stewart in his only overseas press conference. (Jimmy Stewart Museum photo)

Stewart didn’t want notice made of his service. He insisted that reporters stay away; he didn’t want media to distract him from his service. During World War II he made a couple short enlistment films, including Winning Your Wings directed by John Huston, but only gave one short overseas press conference.

Winning your wings an Army Air Forces enlistment film. (National Archives)

Stewart was promoted to major in January 1944, but only after refusing the promotion until his pilots received promotions as well. He became commander of the four-squadron 445th, but still flew missions as the co-pilot with various crews; frequently the pathfinder planes that arrived first and put off flares to help bombers locate the target.

The combat missions that Stewart flew were not without peril. Flight crews faced temperatures of -40 degrees F in their unpressurized planes, and had to constantly knock ice off of their oxygen masks. Some missions were too far to have constant fighter protection, so the bombers flew alone, facing enemy fighters.

On one trip during the winter of 1944, an anti-aircraft shell burst in the wheel well of the plane, creating a large hole between the pilot and co-pilot and through which they could see the German countryside miles down. Stewart lost his map case and parachute in the explosion, and when the plane landed, it cracked in half. Stewart remarked to one of the ground crew, “Sergeant, somebody sure could get hurt in one of these damned things.”

In April 1945, Stewart was promoted to colonel and the chief of staff of the 2nd Air Division. He returned to the United States in September 1945, and stood at the bottom of the ship’s gangplank, shaking the hands of all the men he had served with.

Stewart was awarded the Distinguished Service Medal, the Distinguished Flying Cross with oak leaf cluster (indicating another award), Air Medal with three oak leaf clusters, and the French Croix de Guerre with Palm, among others.

Upon returning to Hollywood, Stewart found himself seriously unemployed. He didn’t work in film until director Frank Capra , who had spent the war producing the Why We Fight series of films for the government and who had found no work when he returned to Hollywood, either, offered him a part. Stewart and Capra had worked together before, in You Can’t Take It With You in 1938, and Mr. Smith Goes to Washington in 1939. Capra wanted Stewart to play George Bailey in It’s a Wonderful Life, which didn’t do well at the box office, but has since become a Christmas classic.

Donna Reed and Jimmy Stewart in It’s a Wonderful Life.

Stewart went on to make many more movies, among them Harvey, Anatomy of a Murder, and Winchester ’73. He played in two films about flight: starring as Charles Lindbergh in The Spirit of St. Louis, and Lt. Col. “Dutch” Holland in Strategic Air Command, but due to contract restrictions was unable to do the actual flying in either.

He stayed in the Air Force Reserve, retiring in 1968 as a brigadier general.

Brig. Gen. Jimmy Stewart (Jimmy Stewart Museum photo)

And lest you think that It’s a Wonderful Life is the only Christmas movie Stewart ever made, there’s a no-budget short film he made with the Tabernacle Choir at Temple Square, formerly known as the Mormon Tabernacle Choir, in 1980 called Mr. Krueger’s Christmas. Writer Michael McLean tells of going to meet Stewart at his home. He was shocked at Stewart’s appearance; he was bent, seemed a bit scattered, dressed in an old cardigan and cheap pants. When McLean asked if he was up to the part of Mr. Krueger, Stewart straightened up and energetically replied that he was perfectly capable. It was only then that McLean realized Stewart had been auditioning for the part!

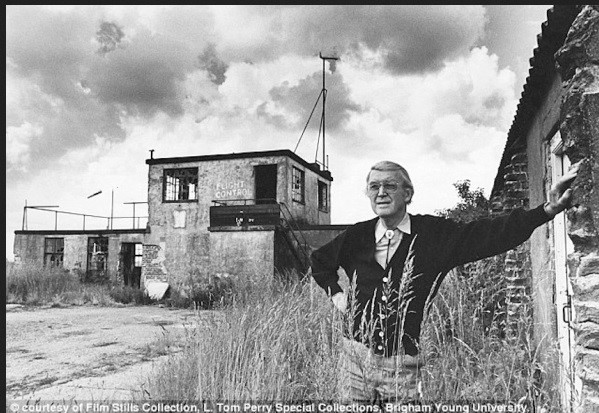

Jimmy Stewart and his wife Gloria had four children, and lived in the same home in California for 40 years. Stewart visited his base in England in 1985, a much different place than he recalled. He died in 1997, never having talked much about his war experiences, like many of his generation.

Jimmy Stewart visiting his Air Forces base in England, 1985. (L. Tom Perry Special Collections photo)

Direct quotes from Mission: Jimmy Stewart and the fight for Europe by Robert Matzen.

Before becoming director of library and archives at the George C. Marshall Foundation, Melissa was an academic librarian specializing in history. She and her husband, John, have three grown children, and live in Rockbridge County with three large rescue dogs. Melissa is known as the happiest librarian in the world! Keep up with her @MelissasLibrary.