Last week, the Associated Press ran an article about the efforts to honor surviving members 6888th Central Postal Directory Battalion with the Congressional Gold Medal. Legislation passed the Senate earlier this year, and a bill is currently waiting on a vote in the House. Information about finding and contacting your local representative can be found at the end of this post.

BOSTON (AP) — Maj. Fannie Griffin McClendon and her Army colleagues never dwelled on being the only Black battalion of women to serve in Europe during World War II. They had a job to do.

The 6888th Central Postal Directory Battalion was credited with solving a growing mail crisis during its stint in England and, upon their return, serving as a role model to generations of Black women who joined the military.

But for decades, the exploits of the 855 members never got wider recognition — until now.

The Senate passed legislation that would award members of the battalion, affectionately known as the Six Triple Eight, with the Congressional Gold Medal.

The bill is awaiting action in the House, but is already too late for most 6888 members. There are believed to be only seven surviving, including McClendon.

“Well, it would be nice but it never occurred to me that we would even qualify for it,” McClendon said from her home in Tempe, Arizona.

“I just wish there were more people to, if it comes through, there were more people to celebrate it,” said McClendon, who has met with her local congressman to press for passage of the bill.

…

The unit’s story has also started gaining wider recognition. A monument was erected in 2018 at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, to honor them, and the 6888th was given the Meritorious Unit Commendation in 2019. A documentary “The Six Triple Eight” was made about their exploits. There is talk of a movie.

A bill would rename a Buffalo, New York, post office after the battalion’s Indiana Hunt-Martin, who died last year.

And there is the push for the Congressional Gold Medal.

“These women were trailblazers, and it is past time that we officially recognize them for their incredible contribution to our troops during World War II,” said U.S. Sen. Maggie Hassan, a New Hampshire Democrat who co-sponsored the Senate bill.

Like McClendon, Moore’s family said she would be honored but not enamored by the award. She rarely talked about her time with the 6888th when she was alive, preferring to let those achievements speak for themselves.

“She would have said, ‘This is an amazing, wonderful honor and I’m very proud to have served.’ Then she would have went on with her life,” said Moore’s niece Elizabeth Pettiford, who grew up next door to Moore in Portsmouth, New Hampshire. “I just don’t think she would have made a huge thing about it because that was her personality. She kept a lot of things in.”

This blog, which first ran in August, 2020 tells the story of the 6888th:

The 64th anniversary of the dedication of the Colleville-sur-Mer Normandy American Cemetery was commemorated July 18. Among the thousands of graves, there are four American women buried there – three from the same battalion: the 6888th Central Postal Directory Battalion.

The 6888th Central Postal Directory Battalion consisted of 850 officers and enlisted in four companies, and was the only female African-American unit sent overseas. Their commander, Maj. Charity Adams, was the first African-American woman to be commissioned.

The women trained at Fort Oglethorpe, GA. It was typical basic training – running and jumping; learning to wear gas masks, identify enemy materiel including ships, airplanes, and weapons; they climbed ropes; learned to board and evacuate ships and did long rucksack marches.

Maj. Charity Adams and Capt. Abbie Campbell at the unit’s first inspection. Army Historical Foundation photo.

In January 1945, the women traveled by train to Camp Shanks, NY, where they sailed for Glasgow, Scotland on Feb. 3, 1945, and then rode a train to Birmingham, England, their station. The enlisted women were housed in the old King Edward School, and the officers stayed in two houses.

Some of the 6888th in front of Old King Edward School in Birmingham, Eng. Army Historical Foundation photo.

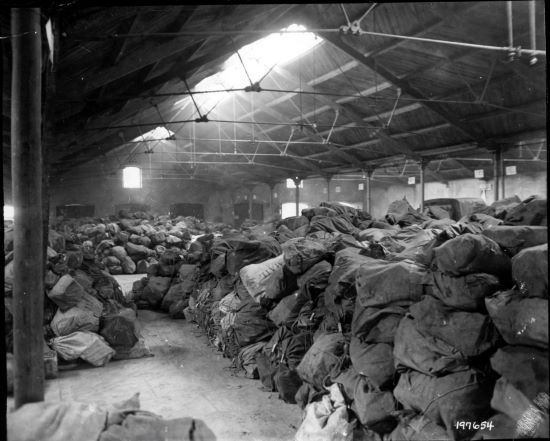

Their workspaces were unheated and poorly lit airplane hangars stacked floor to ceiling with mailbags, some two years old. Packages with homemade goodies had long been ransacked by varmints. Much of the mail was addressed incorrectly – to old addresses, or simply no address; “To Junior, Gloucester.” Many service members shared names; 7,500 were named Robert Smith.

Airplane hangar in Birmingham, Eng., filled with mail and packages. Women of the 6888th photo.

The unit developed a card system to identify all seven million military and serving civilians in the theater and where they were most currently stationed. They worked around the clock, three shifts a day, handling an average 68,000 pieces of mail a shift, which they sorted, and rewrapped and readdressed when necessary. Their motto was, “No mail, low morale.”

The enlisted women were housed in the old King Edward School, and the officers stayed in two homes in the area. Mattie Treadwell, author of Women’s Army Corps, the official history, tells of an inspection the unit had:

When a male general came to inspect the unit, Major Adams prevented him from viewing the women’s private rooms while some of them were sleeping. After headquarters and off-duty personnel of the unit were assembled in a formation as instructed, the general chastised Major Adams for not having all her troops present. When Major Adams attempted to explain that the women worked three different shifts and that she followed the orders she was given, the general cut her off and threatened to send a “white first lieutenant” to show her how to command the unit. Major Adams’ famous reply, “Over my dead body, Sir,” nearly earned her a court-martial, but the general was subsequently dissuaded from taking that course of action. By the time the same general visited the unit in France, his attitude had changed and he appreciated the 6888th’s accomplishments (p. 600).

WACs from the 6888th with one of their motor pool vehicles. Center of Military History photo.

The 6888th was a self-sufficient unit; they had their own medics, dining hall, military police (who were not armed, but were trained in ju jitsu), transportation, administrative and support services. While Red Cross social facilities were not segregated, African-American military women were not permitted entrance. The unit had their own social organizations and sports teams, and refused to use the special facility the Red Cross opened for African-American women only.

Military authorities estimated that it would take at least six months and closer to a year to get the backlog taken care of. It took three months.

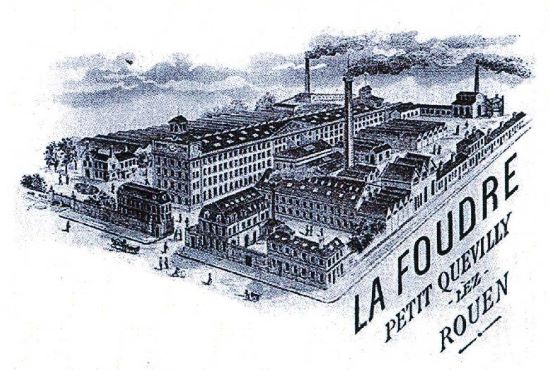

Barracks in Rouen, Association Nationale des Villes et Pays d’art et d’histoire et des Villes à secteurs sauvegardés et protégés photo

In May 1945, the 6888th was moved to Rouen, France, about an hour east of the port city of Le Havre. They were housed in an old mill complex, La Foudre, which had been purchased by the French government and turned into barracks just before World War II.

Their new working conditions resembled the old – a gigantic backlog of undelivered mail and packages. This time, they were not working alone; French civilians and German prisoners of war were working with them. Again, working shifts around the clock, the women had the backlog cleared out in three months.

Members of the 6888th working with French civilians and German prisoners of war in Rouen. Center of Military History photo.

Marching in a parade at the marketplace in Rouen where Joan of Arc was killed. Army Historical Foundation photo.

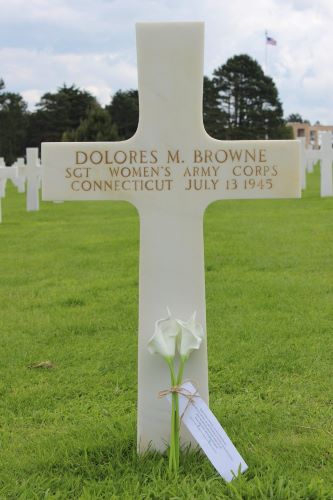

It was while the unit was stationed in Rouen, on July 8, 1945, that Pfc. Mary J. Barlow, Pfc. Mary H. Bankston, and Sgt. Dolores M. Browne were killed in a jeep accident. The unit members paid for caskets and organized memorial services for the women, and they were buried in the Normandy American Cemetery. Maj. Adams had the hardest duty for a commander – writing the women’s families.

Pfc. Mary Barlow’s grave in Normandy American Cemetery. Canadian Force in the U.S. photo

Pfc. Mary Bankston’s grave in Normandy American Cemetery. Canadian Forces in the U.S. photo

Sgt. Dolores Browne’s grave in Normandy American Cemtery. Canadian Forces in the U.S. photo

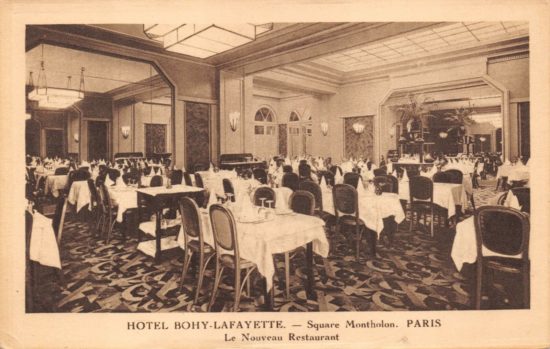

After five months in Rouen, the unit was transferred to Paris. Here, the enlisted women were billeted in the Hôtel Bohy-Lafayette, and the officers at Hôtel États-Unis. These were much nicer and more comfortable than previous situations and offered maids and a restaurant to eat in.

Hôtel Bohy-Lafayette restaurant. DelCampe photo.

Hôtel États-Unis. All France Travel photo.

The working conditions, however, were much the same. The warehouse didn’t have heat, so the women still wore layers upon layers to work in the winter. There were French civilians working with them, and the deprivations of years of war made the contents of packages too tempting for some, and so unit members had to search the local workers daily to recover stolen items.

Shortly after peace was declared, the 6888th basketball team was to play in a military tournament in Stuttgart, Germany. However, they couldn’t get seats on the segregated train. Gen. John C. H. Lee, deputy theater commander, intervened and had his special car attached to the train for the team members to travel in. The women won the tournament.

In February 1946, the unit returned to the United States and was disbanded at Fort Dix, NJ. There were no victory or homecoming parades, and no official recognition of the importance of their accomplishing the impossible in little time. The only note of a job well done was that Maj. Adams was promoted to Lt. Col. on arrival home.

Photos from:

Armyhistory.org

U.S. Army Center of Military History

English Army History Society

Association Nationale des Villes et

Pays d’art et d’histoire et des

Villes à secteurs sauvegardés et protégés

Canadian Forces in the United States twitter

The bill, H.R. 1012, can be found here: https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/house-bill/1012/text?r=16&s=1

Want to help get it passed, and see the surviving members of the 6888th Central Postal Directory Battalion get the Congressional Gold medal? Call your Congressional Representative.

The list of Representatives, by state and district: https://www.house.gov/representatives

Not sure of your district? This link locates representatives by your ZIP Code: https://www.house.gov/representatives/find-your-representative

Melissa has been at GCMF since fall 2019, and previously was an academic librarian specializing in history. She and her husband, John, have three grown children, and live in Rockbridge County with three large rescue dogs. Keep up with her @MelissasLibrary.