The digitization of 63 Hollinger boxes of Army Signal Corps photos is an ongoing project at the Marshall Foundation Library. VMI cadets Garrett DeFazio and Noah McHugh, and missionaries from the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints Elders Larsen, Finney, and Eaton have been moving this project along this summer, and sometimes discover some amazing photos that lead to stories. This blog is one of those stories.

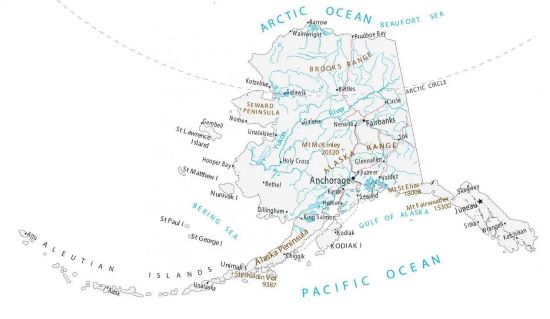

Point Barrow (Nuvuk, here labeled as Nuwuk)

Barrow (Utqiagvik) shown on the Arctic Ocean.

Before you begin reading the blog, you will find it useful to know that Point Barrow (Nuvuk, also spelled Nuwuk), AK, is the northernmost community in the United States, on a small spit of land in the Beaufort Sea . In the 1920s and 1930s, it had a population of about 85. It’s about nine miles from Barrow (Utqiagvik), a better-known town of about 300 at the time. Neither community is accessible by road. Although it’s only nine miles from Nuvuk to Utqiagvik, polar bear activity in the area made it an unsafe hike. The only way to travel was by dog sled.

In the 1930s, there was a radio communications and weather station in Nuvuk. The station was manned by Tech Sgt. Stanley R. Morgan, of Payson, UT, and his family – his wife, Beverly; his daughter Beverly; and his son, Barrow.

Sgt. Stanley Morgan and his daughter, Beverly, and son, Barrow, about 1932.

Beverly Morgan with the children about 1932.

Morgan was in charge of communications and his wife was in charge of weather measurements. These services provided vital communication and information for ships and air travel, the main way of transporting goods to the area.

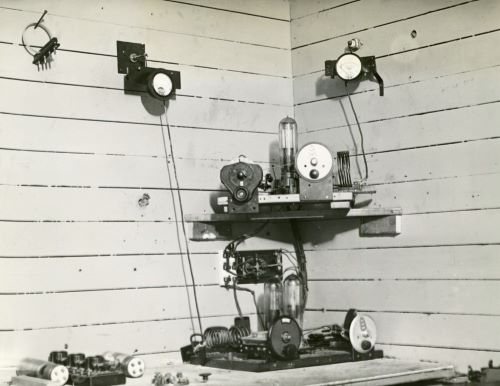

The station started out bare bones with a simple transmitter/receiver to see if communications would work.

Over time, the set up became more complex.

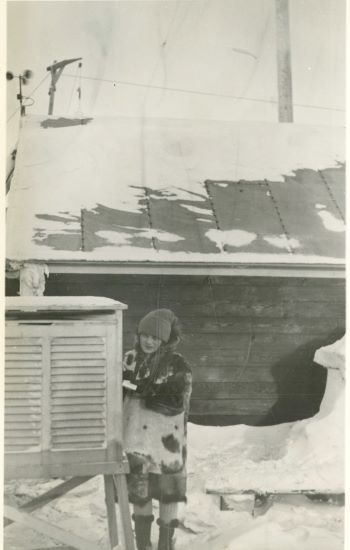

Beverly, taking a temperature reading; it was -58 degrees Fahrenheit.

Beverly measuring the snow depth.

Morgan working at the Communications station.

Since he was the only soldier assigned to the station, he was responsible for it at all times, even when he was sick. In April 1935, the small community endured an influenza epidemic. Morgan had influenza and pneumonia and still worked to get help for community, for which he was awarded the Soldier’s Medal.

TSgt. Morgan with the Soldier’s medal.

The sea around Nuvuk was ice-free for about 10 weeks, from mid-July through October, for boats to bring supplies. Some years the ice remained longer, as in the photo below from August 1 one year, showing boats held up in heavy sea ice.

In August 1926, the supply boat Arctic was crushed and sunk by sea ice.

The Morgans had visitors at Nuvuk, including Col. and Mrs. Charles Lindbergh, who flew to Alaska in August 1931.

Left to right: school teacher John R. Trindle, Mrs. Greist, Anne Morrow Lindbergh, David Greist, Sgt. Stanley Morgan and daughter Beverly, Col. Charles Lindbergh, Dr. Greist.

Not all visits ended well. On Aug. 15, 1935, Morgan had the unenviable task of leading the recovery of aviator Wiley Post and humorist Will Rogers, whose airplane had stalled and crashed on takeoff.

In his travels as an Army sergeant and U.S. Commissioner, Morgan found travel by dog sled to be slow and cumbersome. He wrote in a 1933 article for U.S. Army Recruiter, “On the trail, our day’s work is not over until a snow house has been made, temporary shelter erected for the dogs, and above all things, sufficient food taken from the sleigh and cached hand in the snow house.” This made for a long day, and in the twilight of the winter months, made actual travel hours very short. Morgan and his friend, teacher John Trindle, discussed “problems of Arctic travel, wondering why no method of motorized transportation had ever been tried.”

Enter Roaring Boring Alice.

Roaring Boring Alice

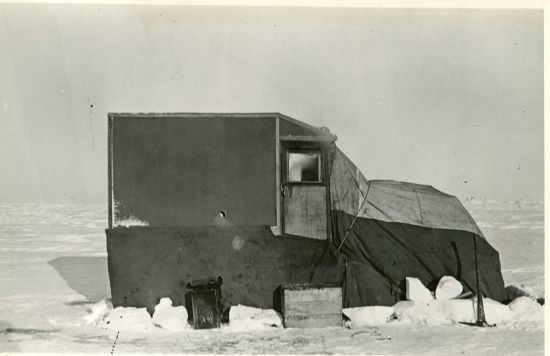

Built from a Model “T” chassis, with skis in front and double tires with chains in the rear, accompanied by skis as well. A canvas “house” was mounted on the frame and was heated by a gasoline heater drawing directly from the vehicle’s gas tank.

The men developed covering to protect Alice when she was not being driven.

Alice in her covers.

Once completed, Morgan and Trindle took Alice for a drive. “We climbed into the car, started the engine, and drove off across the frozen tundra. A trial run of 15 miles across tundra and frozen-over lakes conclusively proved motorized transportation was practical.”

Morgan’s family and another boy posing with Alice.

On one trip, Morgan and Trindle decided to cross a frozen bay rather than waste time and gas by going the long way around on land. “We started across, and progressed nicely until halfway across, we began to doubt our judgment taking this direct route. Encountering rough ice and open leads of water, we were near the point of turning back, when, looking behind, we found to our astonishment we were on a floating island of ice.” To keep from floating out into the Arctic Ocean, they used the skis to jump Alice from one ice floe to another until reaching land. “When we came near to another pack of ice, to jump the car across, working into shore as rapidly as possible.”

Navigating in the Arctic was tough, as there were no roads, and no signs. On one trip delayed by snow drifts, the two inventors found themselves lost one early night. Of course a magnetic compass does not work in the Arctic and normally, cloud cover obscured the stars.

Alice with blocks of ice holding her covers on.

The weather was often a problem while traveling in the Arctic. Preparing a return trip from Beechey Point back to Nuvuk, a village elder warned the men a storm was coming. “Unfortunately, in our haste, we disregarded this warning. Departing at daybreak, we had not traveled 10 miles when a blizzard hit us. We piled snow and ice blocks around the car to anchor it down, and for five days were forced to remain in this one spot, not daring to leave camp for fear of being lost. Vision was absolutely blotted out; and were we indeed thankful we had no dogs to take care of, no snow house to build, plenty of fuel to burn, and we so comfortably set.” Upon arriving safely back in Nuvuk, “the entire population came out to greet us. Many had given us up for lost. We were pleased with the performance of our experimental car, and had proved the dependability and practicability of motorized methods of travel in the Arctic.” The trip along Alaska’s northern coast would have taken them 30 days’ travel by dog sled; it took them seven by Alice.

Alice after falling through sea ice near shore. She was pulled out with dog sled teams.

The Morgan family stayed in Alaska, but were transferred to the Kobuk and Koyukuk river areas later in the 1930s. On retirement, the Morgans moved to the Kenai Peninsula in south central Alaska.

Roaring Boring Alice stayed in Alaska, too, although now not much more than the Model “T” chassis Morgan and Trindle first started with. Nothing goes to waste in the Arctic, so it’s probable that as motorized transport improved, Alice donated parts to other vehicles. We know Alice still exists from this photo, but we don’t know where in Alaska.

Roaring Boring Alice now.

Maps: GIS and Alaska Climate Research Center

U.S Army Recruiting News Vols. 15 & 16, 1933.

Melissa has been at GCMF since fall 2019, and previously was an academic librarian specializing in history. She and her husband, John, have three grown children, and live in Rockbridge County with three large rescue dogs. Keep up with her @MelissasLibrary.