by David Hein

This essay is excerpted from Teaching the Virtues, the recent book by Senior Fellow at the Russell Kirk Center for Cultural Renewal and long-time Marshall Foundation board member David Hein. In this selection, Hein reflects on how George C. Marshall’s enduring character, marked by restraint, duty, and reverence, was shaped less by ambition than by long-formed habits of service. Drawing on tradition and moral inheritance, Hein offers a portrait of leadership grounded in quiet strength.

Perceptive about the sources of piety within the bonds that unite us, Edmund Burke would have appreciated Josef Pieper’s statement, in The Four Cardinal Virtues, that “the world is not to be kept in order through justice alone.” Within a web of meaning and mutuality, citizens feel gratitude for what they have received from forebears, and their thankful inclinations motivate their concern for future generations. They willingly answer the call of community or country, and duty becomes a habit they do not have to question each time they are challenged to do the right thing. Burke leads us to quiet virtues—prudence, humility, duty, gratitude—that we need to be reminded of in our own time.

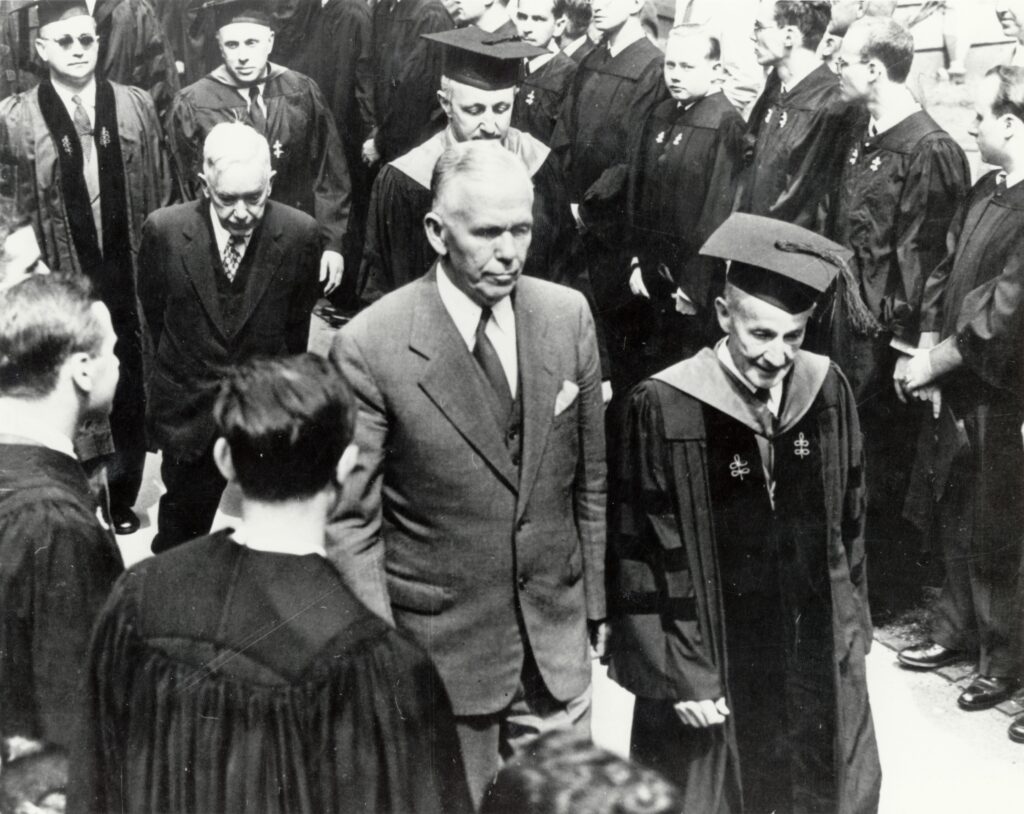

Secretary of State Marshall in procession to receive honorary L. L. D. at Harvard University, June 5, 1947.

We gain a sense of what Burke meant and of his ongoing pertinence when we test his themes in the context of the life of an American general honored for his character as much as for his leadership: George C. Marshall, who personified the virtues of faith, hope, prudence, temperance, courage, humility, patience, and justice. Winston Churchill designated him the “organizer of victory” in World War II. And on June 5, 1947, when Marshall as secretary of state spoke at Harvard University and announced the European Recovery Program (which soon became known as the Marshall Plan), his honorary-degree citation referred to him as “a soldier and statesman whose ability and character brook only one comparison in the history of the nation”—that is, to George Washington.

One of the mediating institutions that most affected Marshall was his home parish, St. Peter’s Episcopal Church in Uniontown, Pennsylvania, where he was baptized at six months of age. The Reverend John R. Wightman, the young rector of St. Peter’s, made a lasting impression on the future general. Marshall recalled him in a letter that he wrote during the Second World War, on August 6, 1943: “Mr. Wightman exercised a profound influence on my character and life. While I was a mere boy in my early teens he honored me with his friendship. We often took walks in the country together, and I spent many hours with him at the Parish House, which had just been constructed.”

Confirmed at St. Peter’s at the age of sixteen, Marshall continued for the rest of his life in the way he had been brought up. Throughout his notable career, Marshall regularly attended church services, and he always tried to build up the churches—both the physical structures and attendance at worship—on the posts to which he was assigned. He ended his days as a faithful communicant of St. James’ Episcopal Church in Leesburg, Virginia.

Historians cite the impact of the Rules of Civility on George Washington and of Groton headmaster Endicott Peabody on Franklin Roosevelt. With at least as much confidence they should name prayer-book spirituality as a steady influence on George Marshall, not only as a boy but throughout his life. Gradual nurture and slow transformation, rather than an emotional conversion experience, marked his religious journey, guided by the words and actions in the Book of Common Prayer.

This text’s influence on the language and literature of English-speaking peoples rivaled that of the Authorized Version of the Bible and the works of William Shakespeare. As a boy, Marshall would have been brought up on the 1789 American version of the Book of Common Prayer. Its direct descendants were the revisions of 1892 and 1928, in which Marshall would have continued to feel at home. The prayer book would not be rendered into contemporary American English until twenty years after Marshall’s death. Its 1662 Church of England form—whose words, also, would have been largely familiar to Marshall—was Edmund Burke’s prayer book.

Incorporating large amounts of scripture, prayer-book services were the primary context of Marshall’s virtues. This piety oriented his will and shaped his character. A conservative internationalist, Marshall initiated and helped to secure passage of a program for western European recovery that we can at least say was wholly consonant with both his grand strategy as an American statesman and his practice as a faithful churchman.

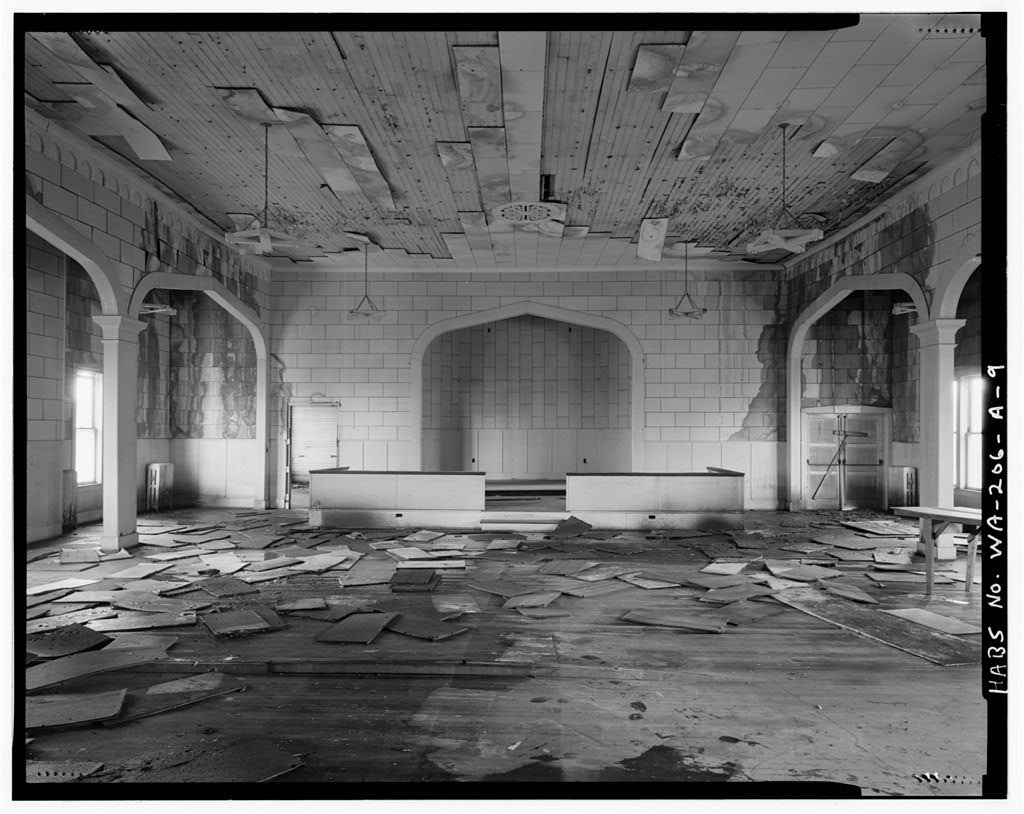

The chapel at Vancouver Barracks in 1933, three years before Marshall led efforts to restore it. He believed faith mattered, and that the post should have a place to pray. LOC photo.

Former secretary of state Dean Acheson called Marshall the “least militant of soldiers.” Indeed, Marshall would have prayed the Collect for Peace, in the Order for Daily Morning Prayer, with complete understanding and in a spirit of heartfelt approbation:

O God, who art the author of peace and lover of concord, in knowledge of whom standeth our eternal life, whose service is perfect freedom; Defend us thy humble servants in all assaults of our enemies; that we, surely trusting in thy defence, may not fear the power of any adversaries, through the might of Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen.

In his personal history of the Church of England, titled Our Church, Roger Scruton analyzes these lines and comments, “The phrase ‘whose service is perfect freedom’ is a rebuke directed to those who think that freedom and authority are in conflict.”

Freedom does not conflict with true authority. In this prayer, Omnipotence and Omniscience (“in knowledge of whom standeth our eternal life”) are established as “the author of peace and lover of concord” and hence trustworthy. But even more: God is for us and not against us. We know this truth because in his service lies our perfect freedom. To serve this One liberates our authentic selves. Confidently, therefore, we can ask God to defend us “in all assaults of our enemies,” so that, “trusting in thy defence,” we may not live in fear.

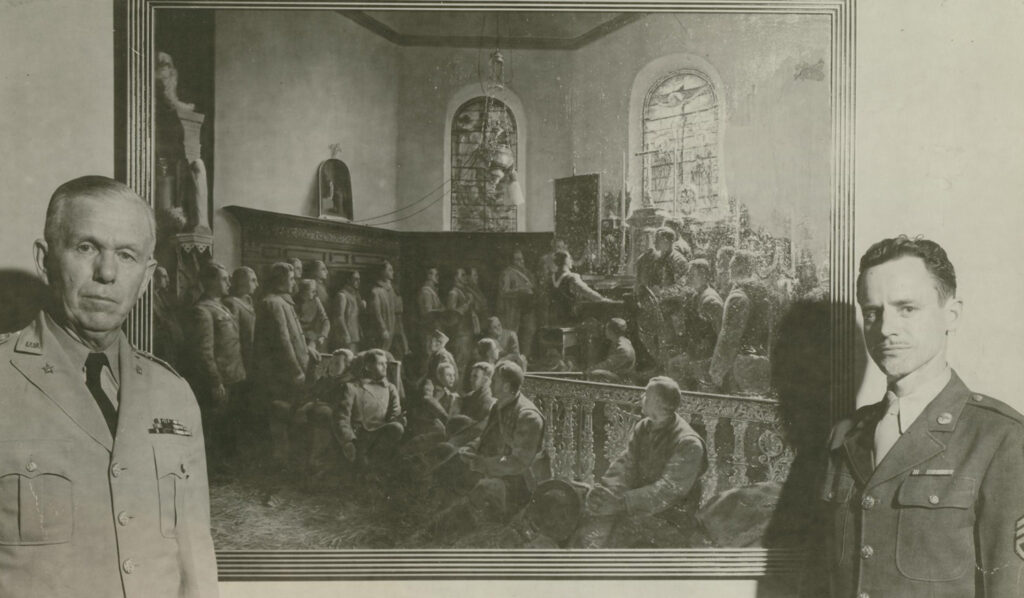

Interior of church with troops of the 317th and 319th Ambulance Companies and 305th Sanitary Train singing in Vaux, Ardennes, France, 1918. Frustrated by portrayals of soldiers drinking and carousing, Chief of Staff George C. Marshall commissioned an oil painting of this reverent scene to hang in his Pentagon office.

The prayer books that Burke and Marshall came to know almost by heart included clear statements of human fallenness: an unpopular theme today, even in churches. The General Confession, which the congregation recited at every service of morning or evening prayer, acknowledged the drag of selfishness on even our best efforts: “We have followed too much the devices and desires of our own hearts.” These words reinforced worshipers’ sense of humility before God and one another. Burke prized this virtue, affirming its value in the thinking and practice of politicians and statesmen.

The prayer book incorporated another motif besides sinfulness: forgiveness, reconciliation, peace, and, as we have just seen, freedom. This mixture of themes in the Book of Common Prayer—sin and grace, tragedy and triumph—amounted to “Christian realism” before the theologian Reinhold Niebuhr made that phrase widely known. Marshall’s conservative internationalism incorporated Christian realism.

These themes came together in the regular celebration of the Lord’s Supper. Many times Marshall would have participated in the sacrament of Holy Communion. This service had a good bit of humility for believers to take on, especially in the Prayer of Humble Access: “We are not worthy so much as to gather up the crumbs under thy Table.” But this same prayer concluded with the petition that we might partake of Christ’s body and blood so “that we may evermore dwell in him, and he in us.” Dominant was this hopeful theme of incorporation, not only later on, in God’s “everlasting kingdom,” but also here and now.

Thus this prayer-book rite included a powerful stress on grace as mutual indwelling. After receiving the bread and wine, communicants gave thanks “that we are very members incorporate in the mystical body of thy Son, which is the blessed company of all faithful people.” Then they prayed that God would “assist us with thy grace, that we may continue in that holy fellowship, and do all such good works as thou hast prepared for us to walk in; through Jesus Christ our Lord.”

General Marshall receives painting made by Staff Sergeant Wallace E. Brodeur from the photograph reproduced above, May 21, 1945. GCMF photo.

Marshall’s piety focused first on God as center of value, then on country and family. From George Washington and undoubtedly from other sources and experiences, he learned and took to heart the virtue of duty—answering without wavering when duty called—so that, even when he would have preferred to retire from public life, he still said “yes” to his nation’s summons. This sense of responsibility—doing what he knew he ought to do rather than what he would have liked to do—became second nature to him.

This ethical awareness—or, more precisely, this steady purpose—is what Burke, in Reflections on the Revolution in France, means by “prejudice,” which, he says, “does not leave [a person] hesitating in the moment of decision, sceptical, puzzled, and unresolved.” Virtues coalesce to form character so that reliability in moral practice, rather than “a series of disconnected acts,” becomes a person’s consistent pattern of behavior. In this way, “duty,” Burke notes, “becomes a part of [a person’s] nature.” So it was with General Marshall.

Burke’s misgivings about the reigning, liberal understanding of “contract” are well known. Our larger “connexions,” to use his word, are decisive. Rather than resembling a contract in civil law, our social relations and obligations ought to be viewed with “reverence” as “a partnership” in knowledge, in art, and “in every virtue.” Burke had a profound grasp of social order and of the moral duty that these relations entail: obligation impelled by gratitude.

General Marshall with Lt. Col. Florence Newsome, the only woman on the General Staff. Their work together reflects the competence and character Marshall valued above status or background. GCMF photo.

In his short book Conservatism: An Invitation to the Great Tradition, Roger Scruton unfolds the implications of Burke’s “defence of the social inheritance.” Not contract but trusteeship is what Burke had in mind: “a shared inheritance for the sake of which we learn to circumscribe our demands” and to see our place “as part of a . . . chain of giving and receiving.” Seen from the perspective of trusteeship, “the good things we inherit are not ours to spoil but ours to safeguard.” Therefore, Scruton points out, we proceed not by “cost-benefit calculations,” as we might if we were deal making prior to a favorable contract, but by “seeing ourselves as inheriting benefits and passing them on.” And here is the key point: “Concern for future generations” is an expression of our “gratitude” for what we have received.

Never a regular student of political philosophy, Marshall nonetheless knew in his bones just what Burke had in mind. The American general never forgot what free citizens owe to warriors in a just cause. When in 1953 he accepted the Nobel Peace Prize, he referred to “the cost of war in human lives . . . constantly spread before me.”

Speaking to college students in Frederick, Maryland, in 1951, Marshall urged his listeners to “appreciate” what America means and to “cease to accept as a matter of course your blessings, your rare good fortune.” If you do appreciate these gifts, then “you will turn seriously . . . to the problem of what you personally can do to see that the United States . . . continues a great democracy and a bulwark of freedom.” In these remarks, Marshall identified the single virtue that both inspires an individual’s personal contribution and buttresses liberty and constitutional governance because it is the only fitting response to those who secured our freedoms “inch by inch”: gratitude.

In a vignette from the Second World War, we can see Marshall’s devotion to his family. The human cost of this conflict was brought home to him when he received a radio message on May 30, 1944, from General Mark Clark, commander of the Italian campaign. It informed the Army chief of staff that his stepson, Lieutenant Allen T. Brown, the twenty-seven-year-old son of his wife, Katherine, had been killed in action the previous day near Velletri, south of the Alban Hills, as his tank unit advanced toward Rome. A loving stepfather, Marshall was devastated. It was a week before D-Day in France. Following his fact-finding visit to Normandy on the heels of the invasion, Marshall on June 18 visited Allen’s grave at the temporary Anzio cemetery, interviewed members of his stepson’s crew, flew over the battle terrain in an observation plane, and worked to reconstruct the action surrounding Allen’s death at the hands of a German sniper.

In Marshall’s life and career, we can easily discern the presence of pietas: reverence toward God, country, and kinsmen. And we can detect the elements in his upbringing that shaped pietas. His soundly constructed piety ordered his soul, oriented his virtues, and contributed to the common good.

About the Author

David Hein is Distinguished Teaching Fellow at the Russell Kirk Center for Cultural Renewal. He earned his PhD from the University of Virginia and has extensive teaching experience at the high school and college levels. Professor Hein serves as a trustee of the George C. Marshall Foundation and of Saint James School. He is the author or coauthor of five other books, and he writes frequently for the New Criterion, Modern Age, Touchstone, the Journal of Military History, Army, the Journal of Ecclesiastical History, and other publications. He is a Fellow of the Royal Historical Society (UK).

Related

Marshall and the Church at Vaux

Marshall, the Vancouver Barracks, and Its Altar