by Dr. Benjamin Runkle

It is difficult to overstate the esteem in which the men who led or served with George C. Marshall during World War II held the U.S. Army chief of staff. Dwight D. Eisenhower wrote that “our Army and people have never been so indebted to any soldier.”

President Harry S. Truman famously said of Marshall’s role as Army chief of staff during World War II: “Millions of Americans gave their country outstanding service.…George C. Marshall gave it victory.” Similarly, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill would describe Marshall as “the Organizer of Victory.”

Knowing what Marshall achieved in recruiting, training, and deploying an army more than twice as large as World War I’s American Expeditionary Force, it is easy to look at photographs of then-Colonel George C. Marshall standing beside General John J. Pershing—whether returning from France in 1919 or during his years as Pershing’s aide at the War Department—and perceive Marshall’s rise as inevitable.

Yet while in retrospect history often appears to have unfolded in a straight line, reality is almost always more chaotic and uncertain. Indeed, Marshall’s eventual triumphs were anything but predetermined, and two underappreciated factors were critical to Marshall’s ascent to the position of Army chief of staff that made the Allied victory: luck and resiliency.

It is understandable, perhaps, that Marshall’s luck is overlooked, as the natural tendency upon hearing somebody described as having been “lucky” is to interpret this as a dismissal of their abilities. In military matters, however, there is greater appreciation for the role that “providence” or “fortune” plays in even the greatest commanders’ careers. In On War, Clausewitz observed that “No other human activity is so continuously or universally bound up with chance. And through the element chance, guesswork and luck come to play a great part in war.” Napoleon may not have been the first to say that he preferred “lucky generals,” but his underlying point about the importance of good fortune in creating opportunities for brilliant commanders to seize is generally accepted by military thinkers. And as legendary British general Sir Edmund Allenby once told a young George Patton, for every Napoleon and Alexander who made history, “there were several born. Only the lucky ones made it to the summit.…[Y]ou had to be at the right place at the right time—you had to be lucky.

Allenby’s assessment is particularly relevant in Marshall’s case. When Marshall matriculated at the Virginia Military Institute in 1897, his dream of obtaining an Army commission was far from guaranteed. At the time, VMI had fewer than a dozen graduates in the U.S. Army. Yet Marshall’s timing was fortuitous, for as he graduated in 1901 the Regular Army was undergoing its first expansion since the Civil War, increasing from 25,000 to 100,000 men to deal with the Philippine Insurrection, and therefore required an additional 1,200 commissioned officers. By the time Marshall was allowed to go before an examining board, there were only 142 positions left for 10,000 applicants. Possessing the good fortune to graduate in 1901 rather than 1899 or 1903 put Marshall in the right place for his talent to earn a commission, as he achieved one of the highest scores on the three-day exam and received his commission as a second lieutenant on January 4, 1902.

Marshall’s luck continued during World War I, when fortune placed him in the same room as Pershing on October 3, 1917, when the AEF commander inspected Marshall’s 1st Division at Gondrecourt. When Marshall had the integrity (and audacity) to publicly disagree with Pershing after the general excoriated the division’s commander, he was lucky that Pershing was the rare general who valued the honest y, judgment, and moral courage Marshall had demonstrated. This led to Marshall’s apprenticeship under Pershing both in France and Washington, D.C., during which he was exposed to mobilization and logistical issues, participated in an in-depth review of the Army’s personnel procedures, and learned how to work with Congress and War Department leaders. This experience would reap enormous benefits when it came time to organize and build an army himself two decades later.

But for Marshall to even reach this point required another stroke of luck during the war. A halfhour before the armistice went into effect on November 11, 1918, a bomb from an American plane accidentally fell and exploded ten yards away from the mess where Marshall was eating breakfast. Marshall was thrown against a wall and stunned, but fortunately only gained a nasty bump on his head. As historian Stanley Weintraub observes: “Had the walls of the old house been less sturdy, a different chief of staff would have led the American armies against the Germans in the next war.”

Although fortune smiled on Marshall at key moments, his strength of character, or resilience, was equally critical in his rise to become a general officer. Today we tend to place the Army’s World War II commanders on pedestals as almost Olympian figures. Yet in reality, during the interwar years they endured numerous personal difficulties that would be recognizable today: divorce, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, professional stagnation, and financial troubles. Marshall was no exception, and endured trials that would have discouraged or even broken a lesser man.

For example, like many officers, Marshall had to endure the disconnect between his abilities and the Army’s glacial promotion system. In the fifteen years after his commissioning, Marshall held nearly every significant staff job in the Army, to include graduating first in his class at the General Services and Staff School at Fort Leavenworth and being asked to serve as an instructor as a mere second lieutenant. Yet despite his reputation for brilliance, Marshall was not promoted to captain until the age of thirty-five—nine years after he became a first lieutenant. This lack of opportunity for advancement had Marshall considering leaving the Army, and in October 1915 he wrote to VMI’s superintendent informing him of his “tentative plans for resigning as soon as business conditions improve” because “I do not feel it right to waste all my best years in the vain struggle against insurmountable difficulties.” Fortunately, General E. W. Nichols convinced Marshall to stay in the Army, and over the next decade Marshall’s resiliency paid off as he served with great distinction during the war, became Pershing’s senior aide when the general became chief of staff, and served as executive officer of the prestigious 15th Infantry Regiment in Tientsin, China, from 1924 to 1927.

Shortly after returning from China, however, Marshall encountered tragedy rather than good fortune. In 1927 Marshall became an instructor at the U.S. Army War College in Washington, D.C., an assignment he had previously turned down five times. Soon after he started teaching, his wife Lily died unexpectedly following a thyroid operation. Marshall was overcome with grief. “Twenty-six years of most intimate companionship, something I have known since I was a mere boy,” he said in a letter to Pershing, “leaves me lost in my best efforts to adjust myself to future prospects in life.” In the void left by Lily’s death he suddenly found his situation unbearable. “At a War College desk,” he confided to a friend, “I thought I would explode.”

Fortunately, the army rallied to its own. Chief of Staff Charles F. Summerall, under whom Marshall had served in the closing days of World War I, offered him some options: he could remain where he was; he could transfer to Governor’s Island, New York, to serve as chief of staff for a corps area; or he could become the assistant commandant of the Infantry School at Fort Benning. Marshall chose Benning and by early November was on his way to Georgia.

Marshall is commonly portrayed as a stoic, aloof figure. Yet shortly after Lily’s death he confessed to his young friend Rose Page: “Rose, I’m so lonely, so lonely.” Despite the presence of friends like Joseph Stilwell and Forrest Harding at Benning, Marshall remained mired in the grip of his personal tragedy. Under the strain of constant work and his loneliness during his first years at Benning, Marshall lost weight, and his lean, bony face became more drawn and plainer than ever.

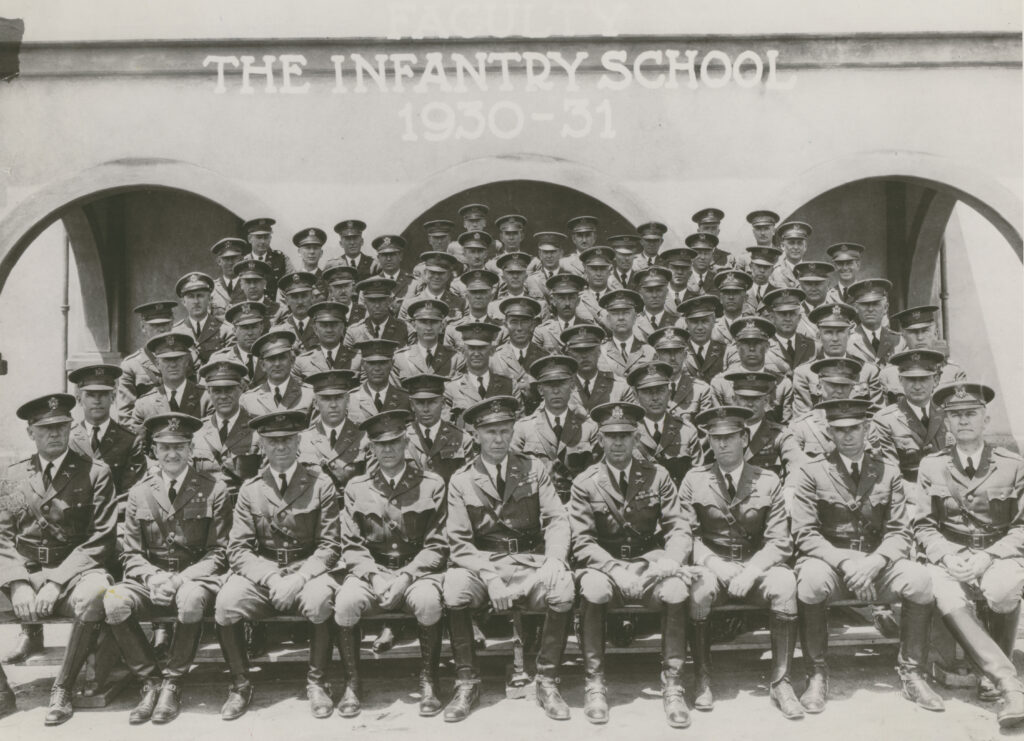

Yet Marshall was resilient and plunged enthusiastically into his new assignment. In what became known as “The Benning Revolution,” Marshall dramatically changed how infantry officers were taught—prohibiting canned lectures and increasing field problems to 80 percent of instruction—as well as what they were taught—emphasizing firepower, maneuver, and above all, creative thinking in place of formal orders and rigid adherence to doctrine. Historian Jorg Muth, who is extremely critical of professional military education and leadership development in the interwar Army, concludes: “The only highlight of the U.S. Army’s educational system in the first decades of the twentieth century was the Infantry School and then only when George C. Marshall was the assistant commander.”

In all, 150 future generals attended the Infantry School during Marshall’s tenure there from 1927–32, and another fifty served on the faculty. One of those instructors was Omar Bradley, who observed that: “Equally important was the imaginative training Marshall imparted to the countless hundreds of junior officers who passed through the school during his time and who would lead—often brilliantly—the regiments and battalions under the command of those generals.” Bradley further stated in his memoirs that “no man had a greater influence on me personally or professionally” than Marshall. It is no exaggeration to say that Marshall’s tragedy inadvertently proved fortuitous to the American effort in World War II because it provoked in him a spirit of tremendous resilience.

Another example of Marshall’s extraordinary resilience came after his tenure at Fort Benning. In October 1933 Marshall received orders relieving him of command at Fort Moultrie and transferring him to Chicago to be senior instructor with the Illinois National Guard’s 33rd Division, a significant setback to his career. Marshall vented to Pershing: “I have had the discouraging experience of seeing the man I relieved in France as G-3 of the army promoted years ago, and my assistant as G-3 of the army similarly advanced six years ago.” Marshall’s despair was so great that for the first time in his career he asked to have his posting changed. Unbeknownst to Marshall, the assignment was ordered by Chief of Staff Douglas MacArthur, who still bore a grudge against Pershing’s staff for perceived slights during World War I. MacArthur told the secretary of the General Staff, Robert Eichelberger, that Marshall “will never be a brigadier general as long as I am Chief of Staff,” and refused Marshall’s request for transfer.

Marshall wrote resignedly to Pershing: “I can but wait, grow older, and hope for a more favorable situation in Washington.” His second wife, Katherine, remembered that during those first months of exile in Chicago, “George had a grey, drawn look which I had never seen before.” His disappointment notwithstanding, Marshall continued mentoring his former subordinates. In October 1934 he advised a former Infantry School instructor not to allow rank and infrequent promotion to ruin his morale. “Keep your wits about you and your eyes open; keep on working hard; sooner or later the opportunity will present itself.”

Marshall took his own advice and turned the 33rd Division into one of the best National Guard outfits in the country. He approached his duty with his usual professionalism, and in the summer of 1934 federal inspectors found every unit of the 33rd at least satisfactory, the first time in years the division had passed muster. After observing Marshall for several months, the 33rd’s commander, Brigadier General Roy Keehn, went to see MacArthur in Washington and told him that Marshall was too gifted to be wasted in a Guard position. Keehn insisted Marshall be promoted to brigadier general and given a challenge worthy of his talents.

Finally, by 1936 Marshall was high enough on the seniority list—and MacArthur was no longer Chief of Staff—to receive what almost everyone realized was a long overdue promotion. Within a few days of pinning on his first star he received orders to take command of the 5th Infantry Brigade at Vancouver Barracks, Washington. And then in May 1938 Marshall was transferred to the War Plans Division in Washington, D.C., which Chief of Staff Malin Craig confided was only a temporary assignment to prepare him to become the next deputy chief of staff.

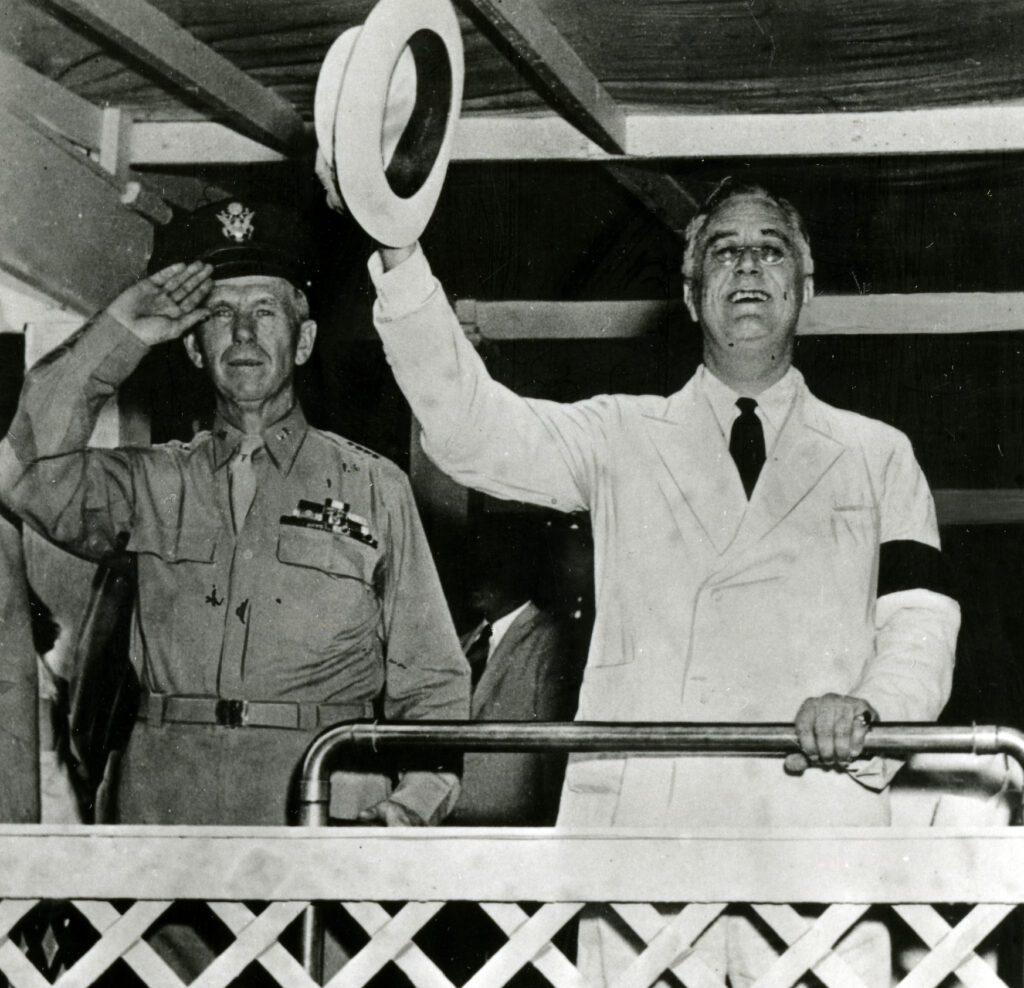

Franklin Delano Roosevelt subsequently elevated Marshall to the Army’s top position in 1939, a promotion that surprised many given that Marshall had dared to openly disagree with the president over the issue of how to develop U.S. airpower—a confrontation that strongly echoed Marshall’s previous clash with Pershing. Yet like Pershing, Roosevelt appreciated that Marshall “would tell him what was what, straight from the shoulder.” Over the next two years, Marshall transformed the inadequately armed and equipped 170,000-man Army into a force of 1.6 million officers and men in 36 divisions and almost 200 air squadrons. He oversaw the passage of the first peacetime draft in American history, the federalization of the National Guard, the establishment of solid relations with the Navy and Congress, the distribution of war materiel to potential allies around the globe, and the creation of detailed manpower and industrial mobilization plans. As Russell Weigley concludes, during this period Marshall became “the principal military architect of the Western democracies’ ultimate victories over the Axis powers.”

Yet for all of Marshall’s intelligence and talent, this achievement was not preordained.

In The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, Edward Gibbon observed: “The fortune of nations has often depended on accidents.” A similar string of accidents and coincidences were vital to the Allied victory in World War II. Although success in war is the product of countless variables, seen and unseen, it can plausibly be argued that without Dwight Eisenhower, Bradley, Patton, “Lightning Joe” Collins, Matthew Ridgway, and other key army and corps commanders, America and its allies would not have been able to defeat Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan. If so, then it could also be argued that since none of these men would have held their commands if not for George Marshall, either due to his direct intervention or because of herculean efforts to expand, train, and equip the Army on the eve of World War II, victory would not have been possible.

It follows that victory in World War II would have been less likely had Marshall not been lucky at key moments nor demonstrated incredible resilience as he endured personal tragedy and professional setbacks. If he had graduated from VMI two years earlier or later, been on the wrong side of a stone wall the morning World War I ended, or not had the fortune to work for leaders who could appreciate intelligent dissent; or had Marshall not had the resiliency to withstand slow advancement, personal tragedy, and professional setbacks, he would not have been in a position to build the forces that defeated fascism in World War II.

Thankfully, he was.

About the Author

Benjamin Runkle is the author of Generals in the Making: How Marshall, Eisenhower, Patton, and Their Peers Became the Commanders Who Won World War II, 1919–1941 (Stackpole Books, 2019). He is a Senior Policy Fellow with Artis International, an Adjunct Lecturer with The Johns Hopkins University’s Global Security Studies program, and a veteran of Operation Iraqi Freedom.