"Turning Into WACs"

by Melissa H. Davis

A version of this article appeared in the Winter 2021-2022 issue of Marshall.

“No official record has been found…that any woman was ever enlisted in the military service of the United States.”

–U.S. Army Records and Pension Office, 1909

Women have served unofficially in the U.S. wartime military since the American Revolution, but officially only since World War II. The earlier contributions of women during our nation’s wars helped U.S. society and the Army see the need for the Women’s Army Corps in 1942.

Historical foundations

Revolutionary War

During the Revolutionary War, many women (and children) traveled with the Continental Army because their homes had been destroyed or occupied by the British. Women had to work to stay; most women served as laundresses – one to each 50 soldiers – and nurses. Nursing was not what we think of now, as during the Revolution, it was considered inappropriate to see a man undressed. The women mostly changed bedding and emptied and cleaned chamber pots.

Some women worked as cooks, carrying coffee, beef and bread to the troops. Sarah Osborn, wife of a soldier from New York, reported that while carrying food one evening she met Gen. George Washington, who asked her “if she was not afraid of the cannonballs?” Sarah replied that “it would not do for the men to fight and starve, too.”

When the Army traveled, the women were expected to carry their belongings like the soldiers did. For their work, they were given a food ration. The women rarely saw pay, but neither did the Continental soldiers.

Civil War

During the Civil War, the Army wanted female nurses to work in the hospitals, to free up men to fight. One notable woman who recruited nurses during the war was Dorothea Dix, who was appointed as the Superintendent of Nurses for the Union Army in June 1861. She helped set the standard of qualifications for women in the nursing corps.

In order for a woman to become a nurse, she had to be between the age of 35-50, in good health, of decent character or “plain looking,” able to commit to at least three months of service, and able to follow regulations and the directions of supervisors. Dix even went so far as to say that women had to wear unhooped black or brown dresses, with no jewelry or cosmetics.

During the Civil War, women disguised themselves as men to fight. Sarah Rosetta Wakeman, 19, enlisted in the U.S. Army as “Lyons Wakeman” in 1862. She served in the Red River Campaign in Louisiana, fighting at Pleasant Hill and Monett’s Bluff. She was admitted to the hospital in New Orleans, gravely ill, and died there in 1864. Wakeman was given a soldier’s burial under her assumed name; her secret never discovered until her descendants told her story 30 years ago.

The Army didn’t admit that women served in combat, however; on October 21, 1909, Ida Tarbell of The American Magazine wrote to Gen. F. C. Ainsworth, the adjutant general of the U.S. Army: “I am anxious to know whether your department has any record of the number of women who enlisted and served in the Civil War, or has it any record of any women who were in the service?” She received a reply from the Records and Pension Office, a division of the Adjutant General’s Office, under Ainsworth’s signature. The response read in part:

“I have the honor to inform you that no official record has been found in the War Department showing specifically that any woman was ever enlisted in the military service of the United States as a member of any organization of the Regular or Volunteer Army at any time during the period of the civil war.”

World War I

In World War I, Army nurses were sent to France, and by June 1918, more than 3,000 nurses were working in British hospitals before American soldiers entered the fight. The nurses held no military rank and were paid the same as enlisted soldiers. While female physicians were refused by the U.S. Army, many were able to serve in hospitals run by the American Red Cross.

To operate switchboards for the new telephone communications in France, the Signal Corps Female Telephone Operators Unit was enlisted. The women, nicknamed “hello girls” (a name they despised), spoke both French and English. They wore identity tags in case of injury or death since they worked so close to the front. Although the women were sworn into the Army repeating the same oath as soldiers, when they got home after the war, they were denied veterans benefits.

Plans for women to serve in the military

In 1920, the War Department established a Director of Women’s Relations, whose purpose was to encourage American women to support the Army. Director Anita Phipps wanted to establish a plan for women to serve in the U.S. military. Her idea was not well received – in 1927, General Headquarters wanted Phipps’ position abolished, noting that “male members of the General Staff were competent to plan the future utilization of women by the military service.” While serving in the General Headquarters Personnel Office, Maj. Everett S. Hughes wrote a report on women in the Army, saying “women would inevitably play a part in the next war. No amount of wishful thinking could avert that necessity, powered as it was by social and economic trends beyond the nation’s powers to reverse.” The head of the Personnel Division, Gen. Albert Bowley concurred, but noted “Successful co-operation between men and women during the next war will depend to a great extent on the attitude of the officers of the Regular Army toward the women of the country. To influence this attitude will require much time and discussion.”

Chief of Staff Gen. Douglas MacArthur discontinued the position in 1931, but Phipps left behind the “first complete and workable plan for a women’s corps.” Both her work and the Hughes report lay forgotten and unused. Shortly after becoming Army Chief of Staff in 1939, Gen. George Marshall asked for a study about women serving in the Army, unaware of the earlier report.

Edith Nourse Rogers, who served in the House of Representatives beginning in 1925, was a field hospital inspector during World War I. Of her experience, she noted, “In the first World War, I was there and saw. I saw the women in France, and how they had no suitable quarters and no Army discipline. Many … who served then are still sick … and I was never able to get any veterans’ compensation for them, although I secured passage of one bill aiding telephone operators. I was resolved that our women would not again serve with the Army without the protection men got.”

“I want a women’s corps right away and I don’t want any excuses!”

– Gen. George C. Marshall

Creating the WAAC

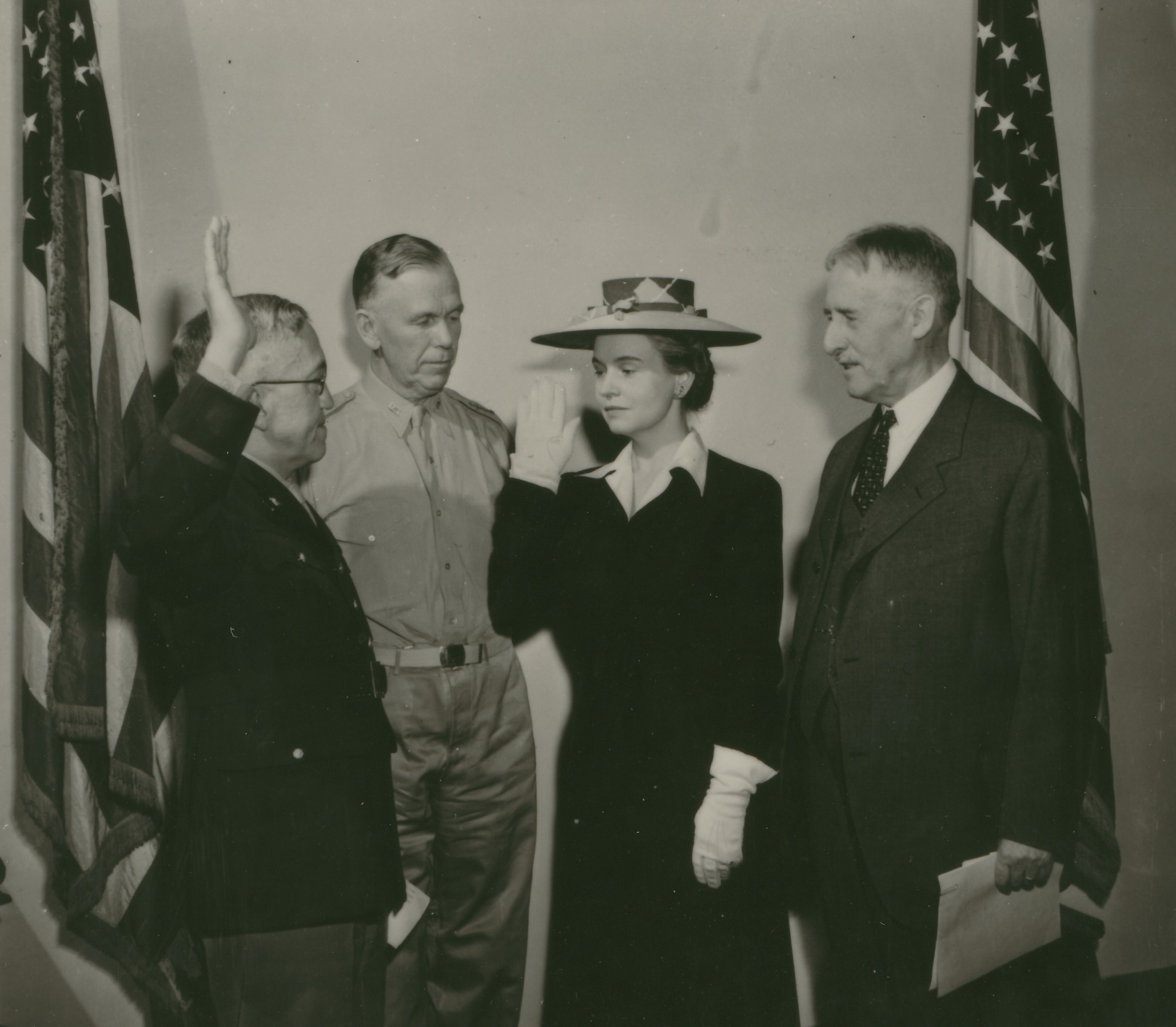

Mrs. Oveta Culp Hobby is sworn in as Director of the newly organized Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps on May 16, 1942. Shown with her are Gen. George C. Marshall, Chief of Staff of the Army, and Henry Stimson, Secretary of War.

Edith Nourse Rodgers, U.S. representative from Massachusetts, introduced a bill to establish the WAAC in May 1941. Pollard Memorial Library

Rogers met with Marshall in the spring of 1941 about women serving in the Army as it became more obvious the United States would not be able to stay out of the war engulfing Europe. Around that time, Marshall wrote, ““We must plan for every possible contingency, and certainly must provide some outlet for the patriotic desires of our women.”

To ensure that the women’s corps would attract the best and brightest, the “educational and technical qualifications should be set exceptionally high” but the list of acceptable jobs included laundry worker and charwoman, according to The Women’s Army Corps. It didn’t seem to matter that the college-educated, professional women they wanted to attract would not wish to perform menial labor. All parties agreed that this new corps was specifically “for the purpose of making available to the national defense the knowledge, skill, and special training of the women of the nation.”

In May 1941, Rogers introduced H.R. 4906, to establish a Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC). Rogers realized that the War Dept was “very unwilling to have these women as a part of the Army” and as written, the resolution did not have sufficient Congressional support to pass.

General Headquarters Chief of Personnel John Hildring wrote: “By the summer of 1941, General Marshall was intensely interested in the WAAC business. He foresaw a cycle of shortages … the bottleneck of the future would be that of manpower. General Marshall asked me why we should try to train men in a specialty such as … telephone work which in civilian life had been taken over completely by women; this, he felt, was uneconomical and a waste of time which we didn’t have.”

The Bureau of the Budget did not agree with Marshall, and objected to the formation of this new corps. “There appears to be no need for a WAAC inasmuch as there will never be a shortage of manpower in the limited services field.” This attitude frustrated Marshall. Hildring reported that “General Marshall shook his finger at me and said, ‘I want a women’s corps right away and I don’t want any excuses!’” Four days after Pearl Harbor, the Bureau of the Budget withdrew its objection.

With War Department input, agreement was eventually reached that up to 25,000 women could serve in noncombat stateside positions. The women would serve with the Army but would not be part of the Army; they would be led by a Director. The women would have a differentiated rank and similar levels of responsibility to soldiers, but would make less: First Officer was comparable to a captain but made lieutenant pay. The Director made $3000 a year, same as an Army major. Lieutenant generals, who commanded the same number of troops as the Director eventually would, earned $8000 a year. The women would receive no military medical care, life insurance, or veterans benefits.

Rogers reintroduced her bill as H.R. 6293. The Congressional Record reports debate on the house floor was heated, and included comments such as if we “take the women into the armed service, who then will do the cooking, the washing, the mending, the humble homey tasks to which every woman has devoted herself?”

In March, anticipating the passage of the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps Act, Marshall wrote to Secretary of War Henry Stimson, “Since the House has passed the above measure by a large majority, we anticipate its quick enactment by Senate. It is, therefore, important that the preliminary arrangements for the organization of the Corps be set up in order to handle the inevitable avalanche of applications. This corps can be of great assistance to our military effort.” Marshall suggested Oveta Culp Hobby, a vice president of the Houston Post newspaper, as a good choice to lead this new group.

WAAC

The bill passed the Senate 38 to 27 on May 14, 1942, and became Public Law 554 “An Act to Establish a Women’s Army Auxiliary corps for Service with the Army of the United States” the next day. Oveta Culp Hobby, publisher of the Houston Post, was sworn in as Director of the WAAC.

The first class of women was due to begin training before the end of the summer, so a suitable location was needed quickly. College and university campuses were not available as most had been taken over to train the men. An old cavalry post, Fort Des Moines, Iowa, was chosen as the first headquarters of the WAAC.

One of the first needs was uniforms. Input from New York fashion designers Philip Mangone and Maria Krum was sought. The War Department wanted uniforms that reflected feminine professionalism, in part to allay fears that women would be outfitted in fatigues. While the designs were lovely, relying on War Department contractors resulted in unsatisfactory results. From Women for Victory: “every component of the outer WAAC summer uniform, except for the stockings, presented serious shortcomings with regard to either appearance, fit, design, material, or functional suitability.” The rush to produce the uniforms meant that readily available male mannequins were used as models, and the sizes were the standard Army short/long. There was no change in the shape of the clothing to fit female figures, so shoulders were too big and busts and hips too tight; nor was there any realization that the handy one-piece male coveralls would be an inconvenient frustration for women as they were required to undress to use the bathroom. The desired materials were in short supply, and the substitute materials resulted in hats that didn’t hold their shape; shoes that fell apart, and raincoats that leaked.

Like male soldiers, it was decided that all clothing that the WAACs would need should be issued to them. The first list of clothing issued consisted of:

- Necktie

- Overcoat

- Raincoat

- Utility coat

- Cap – one dark, one light; summer hat

- Stockings – rayon, cotton, anklet

- Shoes – Service, athletic, galoshes

- Utility bag

- Insignia

- Undergarments – bra, girdle, panties, slip, bathrobe, pajamas

- Exercise suit

- Sweater, gloves, handkerchiefs, and dress shields

This list was more extensive than male soldiers received, and this caused frustration at the War Department. Male soldiers did physical training in their boxer shorts, but this would of course not be acceptable for the women. Pajamas were also a topic of discussion, as the men simply slept in their underclothes, but this also was not socially acceptable for the women. There was a lot of debate on equality vs. fairness of clothing issued to the WAAC.

This resulted in an almost immediate revision of clothing items issued to the WAAC, deleting one of the coats and athletic shoe. The loss of the athletic shoe was sharply felt as the women’s service and field shoes had too much heel to be appropriate for physical training.

Other changes to the WAAC uniform included much-appreciated two-piece coveralls, and permitting women to purchase their own undergarments. Finally, in 1943, the women received slacks as part of the uniform issue. The unforms continued to be problematic, though; the available fabric was too stiff for the intended use and the patterns were designed by men. It wasn’t until May 1943 that the War Department hired a female pattern designer.

In spite of the uniform issues and many other uncertainties, women proved eager to serve. According to Creation of the Women’s Army Corps, more than 35,000 women applied for the anticipated initial 1,000 positions. The first Auxiliary Corps training class consisted of 125 enlisted women and 440 officer candidates; 40 of whom were African American, including Charity Early Adams, the first African American female officer. They reported to the Training Center at Fort Des Moines on July 20, 1942, just two months after the Auxiliary Corps was created.

Director Hobby was present for their arrival and the spectacle of women in uniform drew a lot of press attention. Rebecca Brockenbrough, a teacher at an Episcopal girls’ school in Virginia, trained in the first officer class at Fort Des Moines. Her letters to her sister show what life was like for the early Auxiliary Corps members. On arrival at Fort Des Moines, Brockenbrough wrote,

When we arrived we had to be checked in and that is really red tape. There are 450 officer candidates and approximately 200 [enlisted] auxiliaries. Finally we were led to our barracks and assigned beds, metal wardrobes, and foot lockers. There are 43 beds in our dorm. It was 3 a.m. before we got to bed and at 6 a.m. the band was playing up and down our street.

These first three days we are being processed—turned into WAACs. The post has been swarming with reporters and photographers. I wish I could write what I feel, but you know. It is a fascinating experience and if we can do something worthwhile the work will be very satisfying.

Training in the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps was similar to the basic training men had, including calisthenics and running obstacle courses, close-order drill, attending classes, using military equipment, and completing the constant Army paperwork. Brockenbrough commented that “when I get out of here I’ll be so full of reports I won’t be able to spend a nickel without wondering which form I should use!”

As the Auxiliary Corps expanded, so did Fort Des Moines. Brockenbrough told of the growing pains in another letter:

I am sitting out in the new barracks waiting for the rest of the crew to assemble. In this women’s army you are either rushing or sitting around waiting.

Some sixty-odd buildings are in different stages of production and the mud is knee deep. A tractor is kept here to push the trucks out of the mud! Eventually we’ll get duck-board walks between buildings in our unit but at present we wade through the mud.

As summer turned to fall in Iowa, she noted the surprising change of weather, much different from her home in Virginia: “I’m listening to the weather forecast over the radio and we are promised snow late this afternoon or tonight! That with summer uniforms and no radiators!”

The changing seasons and shortages of winter uniforms and clothing was a problem for the new Auxiliary Corps members. There were creative solutions—women wore non-regulation long underwear with summer uniforms and wore whatever military coats they could find. As Brockenbrough explained, “I finally got a coat—a man’s overcoat size 36. I am completely lost in it and everyone howls when I come around. The first time the Auxes saw me they were in formation and the whole company burst into gales of laughter. Anyway it feels good and I’m not sensitive about my appearance.”

Upon the graduation of the first Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps officers, General Marshall wrote a congratulatory note to Director Hobby, “Their record of the first few weeks gives me great confidence in the future of the corps and the tremendous assistance they will be to the armed forces. We need their enthusiasm, their talents and high purpose. This is only the beginning of a magnificent war service by the women of America.”

Growth of the WAAC and changes in job expectations

The first WAACs in North Africa, attached to Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower’s Headquarters staff, 1943. Army Heritage and Education Center.

It was not intended that the new Auxiliary Corps members serve overseas. They were not given the same securities and benefits as soldiers: they did not have military life insurance or veterans’ health benefits. General Dwight Eisenhower, impressed with the efficient British servicewomen he encountered, asked for five auxiliary corps officers, some of whom spoke French, to serve as executive secretaries just a few days into the North Africa campaign in the fall of 1942.

The first WAACs who arrived in North Africa were followed shortly by a post headquarters company and a signal company. It became obvious that Auxiliary Corps members could not only replace soldiers in some jobs stateside, but also regularly work overseas.

Marshall noted later in correspondence that this “first group of WAC [sic] officers sent to Africa were on a boat which was torpedoed and they made the shore with a loss of most of their clothing.”

The limit of 25,000 for the new corps was soon greatly exceeded by the overwhelming demand of women who wished to serve and the growing needs of the Army, so Secretary of War Henry Stimson raised the limit to 150,000 women.

The rapid growth of the WAAC showed the need for additional training centers, with the second training center opening in Daytona Beach, Florida, in December 1942; the third at Fort Oglethorpe, Georgia, in January 1943; the fourth at Fort Devens, Massachussetts, in March 1943; the fifth training center at Camps Ruston and Polk, Louisiana in March 1943.

The increased number of WAAC members created a shortage of uniforms; many women started training in the one civilian dress brought to training. Sometimes the new WAACs wore men’s uniforms or old Civilian Conservation Corps clothing.

“I am fully convinced that a great deal of the work of the Army can be done better by women than by men.”

– Gen. George C. Marshall

Friction

While Marshall and the War Department were supportive of the WAAC, not everyone was happy that women were serving in uniform. During the spring and summer of 1943, there was an unfortunate effort to undermine the efforts of the Corps. This “slander campaign” discussed in The Women’s Army Corps was “an onslaught of gossip, jokes, slander, and obscenity about the WAAC, which swept along the Eastern seaboard in the spring of 1943, penetrated to many other sections of the country, and finally broke into the open and was recognized in June, after which the WAAC and the Army engaged it in a battle that lasted all summer and well into the next year before it was even partially subdued.”

Marshall wrote a letter of support to Hobby in June, “On my return from Africa I learned of the attack which had been directed against the integrity of the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps. The Secretary of War has already stated in forcible terms the views of the War Department in the matter, but I wish to assure you personally of my complete confidence in the quality and value of the organization which has been built up during the past year under your leadership.”

Changing to WAC

The demand for WAAC units overseas necessitated a change in the status of the Auxiliary Corps. After the first WAAC units traveled to North Africa, Marshall wrote to the House Military Committee that:

I wish you gentlemen to know that in the development of the operation in North Africa it became apparent that General Eisenhower should have, with the least possible delay, women who could speak French to operate the switchboards in Algiers and to serve in a stenographic capacity. The law provides that these women shall not be employed in combat service. They will not be. However, in their present status they do not enjoy the same privileges that members of the Army do who become a prey to the hazards of ocean transport or bombing. At a later date it is the purpose of the War Department to submit to Congress a request for a modification of the law to make this Corps a part of the Army.

In February 1943, with support from the War Department, Representative Rogers introduced a bill to remove “auxiliary” from the women’s corps. The Women’s Army Corps would be soldiers, with the same rank, pay, protections and veterans’ status as the men. President Roosevelt signed the bill into law and in July 1943, the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps became the Women’s Army Corps, an official part of the U.S. Army. The Army Corps personnel had the same rank structure as the Army, and Director Hobby became Colonel Hobby. Marshall supported the Women’s Army Corps; he wrote in a Feb. 15, 1944, letter that “I am probably the strongest Army advocate of the WAC organization and I am fully convinced that a great deal of the work of the Army can be done better by women than by men.”

He further reiterated his support of the Army Corps and expected every commander to support them as well, in a memorandum distributed to every commander throughout the Army:

The Women’s Army Corps is now an integral part of the Army and a highly essential part of our war effort. Its units have met their responsibilities with efficiency and are rendering an invaluable service. However, reports indicate that there are local commanders who have failed to provide the necessary leadership and have in fact in some instances made evident their disapproval of the Women’s Army Corps. The attitude of the men has quickly reflected the leadership of their commanders, as always.

All commanders in the military establishment are charged with the duty of seeing that the dignity and importance of the work which women are performing are recognized and that the policy of the War Department is supported by strong affirmative action.

About the Author

Melissa has been at GCMF since 2019, and previously was an academic librarian specializing in history. She and her husband, John, have three grown children, and live in Rockbridge County with their large rescue dogs.

Related

Lecture: Women of the 6888th Central Postal Directory Battalion by Elizabeth Ann-Helm Frazier