Devising D-Day: Marshall and OVERLORD

by Dr. Mark Stoler

This article is compiled from notes for Dr. Stoler’s March 2024 Legacy Lecture. It previously appeared in the Spring/Summer 2024 issue of Marshall Magazine.

Gen. George Marshall and President Franklin Roosevelt talk at the Casablanca Conference, January 17, 1943.

George C. Marshall was the major and most important proponent of what became Operation Overlord. For the two and a half years before it was actually launched, he had to struggle to convince his commander in chief, Franklin Roosevelt, that this was a good idea. He had to struggle to convince the navy that this was a good idea. He had to fight with the British chiefs of staff to convince them that this was a good idea. And then, of course, he had to convince Winston Churchill that this was a good idea. He was eventually successful. It took two and a half years to do it, only to lose the coveted command himself to his protege, Dwight Eisenhower.

Table of Contents

1941

Nearly a year before Pearl Harbor, Marshall, Chief of Naval Operations Admiral Harold Stark, and their British counterparts had agreed in secret that, in the event the United States entered the war against all the Axis powers, the global strategy would be to defeat Germany and Italy first, before Japan. What they could not agree on was how to first defeat Germany.

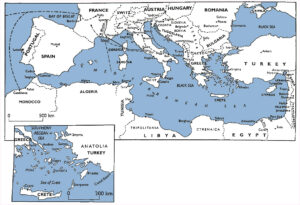

The British proposal favored peripheral warfare, not direct assault, and the use of air power. Churchill advocated “closing the ring” around Germany via land operations in French North Africa and the Mediterranean, forcing its collapse. Most importantly, they wanted to avoid the massive casualties of World War I, where they lost a generation in the trenches. After the fall of France and before U.S. entry into the war, there was no real alternative to this peripheral approach.

Illustration of Arcadia conference by Corporal James Earnst. Marshall can be seen eighth from the left pointing to a map. Fourth from the right is Sir John Dill, with hand extended.

The Americans disagreed vehemently, favoring a direct approach via a massive cross-channel invasion as soon as possible in northern France, to establish what came to be known as the “second front” against Germany after Hitler’s massive invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941. Why? The direct approach has been the traditional U.S. strategy since Ulysses Grant. It is conceived as the most efficient, quickest way to win a war. There was tremendous fear that without this, the Soviet Union would either collapse completely or sign a separate peace with Hitler, in which case the war would be unwinnable given the German casualties taking place on the Eastern Front.

This disagreement was hypothetical—as long as the United States was out of the war. It only became meaningful after Pearl Harbor. Following the attacks Churchill became concerned that the Americans would abandon Germany-first to retaliate against the Japanese. He traveled to Washington with his chiefs of staff to get the U.S. to reassert its commitment to the initial strategy at Arcadia, the first major strategic summit between the two nations of World War II. President Roosevelt, Marshall, Stark—all of them agreed: Allied strategy would remain Germany-first.

They also agreed to a Marshall concept: the innocuous-sounding unity of command. Originally meant for just one theater, but then applied in all theaters of the war, every army, navy, and air personnel under either power would be under a single commander.

Combined Chiefs of Staff, standing behind W. L. Mackenzie (prime minister of Canada), Franklin Roosevelt, and Winston Churchill at Quebec Conference.

Marshall had learned this lesson from World War I, when this did not occur. Churchill was skeptical, asking “What does an army officer know about handling a ship?” Marshall shot back “What the devil does a naval officer know about handling a tank? That’s not the point.”

Churchill then acquiesced.

The U.K. and U.S. also agreed to an American proposal to establish the Combined Chiefs of Staff to run the global war effort. All the commanders would report directly to them, and they would meet in person whenever Roo- sevelt and Churchill met. All other times, they would meet in Washington, with the British represented by the British Joint Staff Mission, headed by Field Marshal Sir John Dill, former chief of the Imperial General Staff, and the man who became one of Marshall’s closest and most important friends during the war.

At Arcadia, the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff (temporarily preoccupied with halting the massive Japanese offensive in the Pacific and southeast Asia) acceded to British peripheral strategy, accepting plans to invade French North Africa (Operation Gymnast), then under the control of the collaborationist Vichy French government.

1942

But very soon after Arcadia, Marshall and his staff planners, led by the then-unknown Brigadier General Dwight Eisenhower, devised a three-part plan to cross the Channel as soon as possible, using British codenames:

1. Bolero The buildup of Anglo-American forces in the United Kingdom.

2. Roundup A spring 1943 crosschannel invasion of forty-eight Allied divisions.

3. Sledgehammer A contingency alternative cross-channel invasion in 1942, with a fraction of the personnel.

The motivation for direct assault was primarily to relieve pressure on the Soviets on the Eastern Front. To illustrate, the United States suffered approximately 405,000 uniform deaths during World War II. The British lost over 700,000. The Soviet death toll, by comparison, was 26 million. Up until D-Day, the Red Army inflicted 93 percent of all German combat casualties, and maintained the majority after the invasion. The three-part plan was meant to help the Russians stay in the war, without whom Allied victory would be impossible.

Why come up with this plan now? First, there was a need to halt the dispersal of U.S. and British forces in light of Axis offenses (and Allied defeats) around the world. Instead, this plan operates on the basic principle of concentrating force on one spot to win the war. Eisenhower, head of the War Plans Division, realized that the logic was circular—a second front was necessary to keep Russia in the war, and keeping Russia in the war was necessary for the successful establishing of that second front. There was also the need for an eventual Soviet second front against the Japanese—quid pro quo.

However, there is no such thing as a purely military plan. They are all political. The army was convinced that dispersion was an integral component of British peripheral strategy and that Roosevelt was dangerously attracted to it, at least partially because this strategy promised quick offensive action in the European theater, which he needed for domestic political reasons. After the war, Marshall said that one of the most important lessons he learned was that in a democracy at war, you must have a successful offensive every year.

There is also the fact that Roosevelt’s naval way of thinking, as former assistant secretary of the navy and sailor, was insulting to the army. Marshall once said “Mr. President, I would really appreciate it if you would stop referring to the Navy as ‘we’ and the Army as ‘they.’” General Joseph Sitwell, as usual, had saltier language for it. “The Navy is the apple of his eye. The Army is the stepchild. Roosevelt is completely hypnotized by the British who have sold him a bill of goods….They have his ear, while we have the hind tit.”

On February 28, Eisenhower wrote a very important memorandum to Marshall, saying there were only three necessary (as opposed to “desirable”) tasks beyond U.S. continental and Hawaiian defense:

1. Maintain Great Britain and her sea lanes.

2. Prevent a German-Japanese junction in India and the Middle East.

3. Retain Russia as an active participant in the war.

The third task was the most pressing and required “the immediate and definite action via Lend-Lease and the early initiation of operations to divert sizable portions of the German Army from the Eastern Front. Such operations,” Eisenhower emphasized, “have to prevent a Russian willingness to end the war, as well as make it militarily possible for the Soviets to continue fighting.” These operations therefore had to be “so conceived and so presented to the Russians that they will recognize the importance of the support rendered.” That meant creating a second front in northern France by late summer of 1942.

Marshall obtained the agreement of the navy and Roosevelt in March, just as Gymnast had been postponed indefinitely. Roosevelt warned that the rough part would be getting the British to agree. Marshall visited London in April, and indeed, Alan Brooke (chief of the Imperial General Staff) called the plan “castles in the air” and considered Marshall a strategic fool for even having suggested it. But Churchill agreed to the American plan.

Roosevelt used this to talk Stalin out of a territorial agreement with Britain that would have recognized his conquests in Eastern Europe between 1939 and 1941. He pressured Stalin into choosing between these territorial gains and his much-needed second front. The Soviets agreed via Minister of Foreign Affairs Vyacheslav Molotov. But continued military disasters such as Tobruk led Churchill and the British chiefs of staff to back away from the 1942 operation entirely. In July, Churchill wrote to Roosevelt advocating for a return to Gymnast, calling it the true second front for 1942.

To say that Marshall and the new chief of naval operations, Admiral Ernest J, King, disagreed would be the understatement of the war. They were livid. They considered this a major breach of faith, and responded with a memorandum to Roosevelt on July 10, 1942, stating that if the British insisted on Gymnast, then the U.S. should go all-out against the Japanese. Marshall claimed later that he was bluffing. King was not. I believe they were very serious in considering this. The Joint Chiefs and U.S. planners believed that abandoning Bolero, Roundup, and Sledgehammer would mean abandoning Russia, making victory over Germany impossible.

Roosevelt forcefully and angrily rejected this in a handwritten message: “Your proposal is hereby rejected. Plan to meet me in Washington on Monday. Signed, Franklin D. Roosevelt, C in C.” The message is clear. In a meeting with Marshall and Secretary of War Henry Stimson, Roosevelt said this was the equivalent of “taking up your dishes and going home.” He also said that the purpose of the memo was a red herring, to scare the British into agreeing to Sledgehammer. He sent Marshall and King to London to reach an agreement on a 1942 offensive in the European theater. Roosevelt’s first choice remained Sledgehammer, but if the British refused, it would have to be Gymnast.

The British vetoed Sledgehammer in 1942, forcing Marshall and King to agree in July to Gymnast in North Africa, now renamed Operation Torch. Eisenhower considered the day that this decision was reached to have been the “blackest day in history.” The Joint Chiefs believed this decision would doom Roundup in 1943, as well as Bolero and Sledgehammer in 1942, and thus was equivalent to giving up on Russia. They also saw Torch as a politically-motivated sideshow to protect British imperial interests in the Mediterranean.

Marshall and King demanded a Combined Chiefs of Staff document that accepted a defensive encircling line of action in Europe, and the transfer of fifteen air groups to the Pacific. Churchill agreed to this small price to pay then flew to Moscow to tell Stalin there would be no cross-channel invasion in 1942.

The meetings were not pleasant, to put it mildly. The battle of Stalingrad had started in July. Stalin made comments about the cowardice of the British army and Churchill, to lighten the mood, said “let us hit the soft underbelly of Europe as well as the hard snout.” Roosevelt’s envoy, Averill Harriman, sitting in on these meetings, said that between Churchill and Stalin, every major city in Germany had been destroyed on paper. Stalin said he had no choice but to accept Churchill’s plans, but Churchill also informed Stalin that Roundup was still planned for 1943.

Thus, at the end of 1942, the allies under Eisenhower would invade French North Africa, right after Montgomery and the British finally defeated Rommel at El Alamein and right before the major Soviet counter-offensive in Stalingrad that isolated the entire German Sixth Army. This is, of course, known as the great turning point of the war. Hitler responded to Torch by taking Tunisia. The operation that Churchill and Roosevelt had hoped would take a few weeks lasted six months, and Tunisia was not retaken until May of 1943. On the other side of the world, the battle for Guadalcanal would not end until January 1943. U.S. forces found themselves tied down in two secondary theaters.

Marshall and Admiral King were humiliated—Roosevelt had accepted Churchill’s views over their own. The American planners were split as to what to do next. In January 1943, Roosevelt called in Marshall and King, asking if armed forces were unified in pressing for Bolero and Roundup that year. Marshall was forced to say no.

1943

When Roosevelt, Churchill and the Combined Chiefs met again in January 1943, in recently captured Casablanca, the divided Americans feared they would be overwhelmed by the united and much better-prepared British. The Joint Chiefs argued for a return to Bolero in order to launch Roundup in 1943. The British argued instead for a continued presence in the Mediterranean in order to take Sicily, in an operation called Husky. The Americans were forced to agree to these plans, as well as prioritizing the U-Boat war in the Atlantic and launching a combined bomber campaign against Germany—without Roundup

Prime Minister Churchill and President Roosevelt sit outside at the Trident Conference. From left to right: Field Marshal Sir John Dill, Lt. Gen. Sir Hastings L. Ismay, Air Chief Marshal Sir Charles F.A. Portal, Gen. Sir Alan Brooke, Adm. Sir Dudley Pound, Adm. William D. Leahy, Gen. Marshall, Adm. Ernest J. King, and Gen. Joseph T. McNarney.

At the end of the conference, Roosevelt announced unconditional surrender as the Allied policy at a press meeting. This was nothing new. Unconditional surrender had always been the common denominator in the grand alliance against Hitler, to avoid a repeat of 1918, which was perceived as a negotiated settlement that led to the “stab in the back” myth and the subsequent rise of Adolf Hitler. And after all, what sort of negotiated peace can you possibly make with a man who had broken every treaty he ever signed? Roosevelt had verbalized the policy as a way of mollifying Stalin in light of meager strategic plans for 1943. In fact, Harry Hopkins had labeled the taking of Sicily as “feeble.” interests in China.

General Albert C. Wedemeyer, one of Marshall’s chief planners, said “One might say [at Casablanca] that we came, we listened, and we were conquered.” When they returned home, they responded by establishing a new committee structure and launching intensive preparations for the next conference (Trident), to be held in Washington, D.C., that May. Those preparations included detailed assessments of the relationship between British strategic proposals and their political motives on the Mediterranean and the negative impact of those political motives on the European war regarding Russia. They also considered the negative impact of British strategic thinking on the Pacific war and postwar U.S.

I describe the American cross-channel strategy as an umbrella policy that could prevent either a Soviet collapse or a Soviet total victory at the expense of the Americans and the British. The fastest way to win the European war, they felt, was to cross the channel en masse, then shift to the war in Japan. The result was a new Joint Chiefs position, with support for continuation in the Mediterranean for 1943—but only if the British agreed to cross the Channel in 1944 and a higher priority for the war against Japan. Marshall got King to agree, and together with Secretary of War Henry Stimson, swayed Roosevelt to the new position. What followed was a united American front against the British at both the May Trident Conference in Washington and the August Quadrant Conference in Quebec.

The meetings were bitter, both times needing to go off the record to exchange very harsh words. However, the Americans agreed to invade the Italian mainland at Salerno (Avalanche) in exchange for British agreement to cross the Channel in 1944 for a smaller-scale Roundup-type operation (first renamed Roundhammer because it was halfway in size between Roundup and Sledgehammer, then renamed Overlord) and higher priority for the dual offensive in the Pacific.

The successful invasion of Sicily in July under Eisenhower led to the overthrow of Mussolini. Hitler sent major forces to Italy in September following the Allied invasion of Salerno. At the same time, relations with Stalin had hit a low point due to another postponement of the second front. They improved with Roosevelt and Churchill’s promise of Overlord in 1944, reiterated at the Moscow Foreign Ministers conference in October and a planned meeting with Stalin in November in Tehran.

But at that very moment, Churchill asked for another delay in Overlord, this time to bring the Italian stalemate to an end and to take the island of Rhodes (Accolade) from surrendering Italian garrisons before the Germans had a chance to replace them, as a way to bring Turkey into the war on the Allied side. Churchill demanded a meeting with Roosevelt in Cairo before the meeting with Stalin in Tehran to discuss this.

Cairo And Tehran

Roosevelt refused to discuss Churchill’s request for the Overlord delay at Cairo, preferring to save it for the Tehran meeting, or to meet privately with the prime minister. Instead, he invited Chiang Kai-Shek to Cairo to ensure the meeting will be dominated by the war against Japan. Churchill claimed Overlord would only be delayed by six weeks. Marshall responded that he had heard that before, leading to an explosive session with the Combined Chiefs of Staff. Stilwell wrote in his diary “Brooke got nasty and King got good and sore. King almost climbed over the table at Brooke. God, he was mad. I wished he had socked him.” Unable to talk to Roosevelt, Churchill vented his rhetoric on Marshall. “His Majesty’s government cannot stand idly by on Rhodes. Muskets must flame.” Marshall lost his temper, responding “Not one American soldier is going to die on that goddamn beach.”

At Tehran, Roosevelt and Stalin agreed, in effect, to an enormous military quid pro quo. Marshall missed the first plenary meeting because it was cancelled and rescheduled at the last minute. Roosevelt, who chaired the meeting, began with a disquisition on the war in Japan. He then explained the situation in Europe, keeping his Pacific maps on the table, telling Stalin that the options were Overlord proceeding on time, or immediate action in the Mediterranean. Stalin responded by promising to enter the war against Japan following the defeat of Germany and chose Overlord over immediate Mediterranean action.

When Churchill asked what was to be done with the forces already in Italy, Stalin reasserted his support for the existing plan to use them following the capture of Rome for an amphibious invasion of southern France (Dragoon) in support of Overlord. He also promised an offensive on the Eastern Front to coincide with Overlord. Churchill argued against this for three daysbut was simply outvoted and overwhelmed by the two emerging superpowers. Churchill later said that this was when he realized what a small country Great Britain was: “There I sat with the great Russian bear on one side of me with paws outstretched, and, on the other side, the great American buffalo. Between the two sat the poor little English donkey, who was the only one who knew the right way home.” But the issue had been settled: Overlord was the basis for the continuation of the Grand Alliance.

The Aftermath

On day two of the Tehran Conference, Stalin asked who was to command Overlord, warning that nothing would come of the operation until someone was chosen. Roosevelt responded that he had not made up his mind. The assumption was that Marshall was the logical choice, with Eisenhower replacing him as chief of staff. Roosevelt had made it clear on numerous occasions that he favored Marshall, telling General John J. Pershing “I want George to be the Pershing of the second World War—and he cannot be that if we keep him [in Washington].” Roosevelt had also said to Eisenhower in Tunis:

Ike, you and I know who was Chief of Staff during the last years of the Civil War but practically no one else knows, although everyone knows the names of the field generals—Grant, of course, Lee and Jackson, Sherman, Sheridan and the others—every schoolboy knows them. I hate to think that fifty years from now practically nobody will know who George Marshall was. That is one of the reasons I want George to have the big command—he is entitled to establish his place in history as a great general.

Roosevelt said this to Pershing and Eisenhower because they and the rest of the Joint Chiefs of Staff were opposed to making Marshall the commander on two grounds. One, it was a demotion—it was a field command while Marshall was in charge of the entire army. Second, Marshall was already running the global American war effort. He had just been named Time magazine’s Man of the Year, and his merits and accomplishments on that front meant he could not be spared.

Roosevelt then attempted to get Marshall to state his own preference. After the Tehran Conference, Roosevelt sent Harry Hopkins to Marshall in Cairo, to obtain an answer. Marshall refused, saying that it was not his decision, and that Roosevelt had to decide what was best for the country, not what was best for George C. Marshall. Finally, Roosevelt brought Marshall to see him in person for a private meeting. The president again asked Marshall if he wanted to lead, and Marshall gave the same answer. Marshall said that Roosevelt responded “Then it shall be Eisenhower. I feel I could not sleep at night with you out of the country.”

So the decision was finally made. Overlord was launched six months later, and we all know what followed. Marshall was not totally forgotten, as Roosevelt had feared. Harry Truman viewed Marshall as the greatest living American and wanted to make sure he was treated properly after the war. He appointed him head of the mission to China, and later Secretary of State and Secretary of Defense. And when Marshall proposed the European Recovery Program in the spring of 1947, it quickly became known as the Marshall Plan. He would later win the Nobel Peace Prize. He achieved immortality in that way.

I would like to conclude with something that Secretary of War Henry Stimson told Marshall on May 8, 1945—VE-Day. He called together a group of senior officers for a brief ceremony, turned to Marshall and said:

I want to acknowledge my great personal debt to you, sir, in common with the whole country. No one who is thinking of himself can rise to such true heights. You have never thought of yourself. Seldom can a man put aside such a thing as being the commanding general of the greatest field army in our history. This decision was made by you for wholly unselfish reasons, but you have made your position as Chief of staff a greater one. I have never seen a task of such magnitude performed by man. It is rare in late life to make new friends. And at my age, it is a slow process. But there is no one for whom I have such deep respect and I think, greater affection. I have seen a great many soldiers in my lifetime. And you, sir, are the finest soldier I have ever known.

About the Author

Mark A. Stoler is Professor Emeritus of History at the University of Vermont, where he taught from 1970 to 2007. He received his B.A. from the City College of New York and his M.A. and Ph.D. from the University of Wisconsin-Madison. He is the author of George C. Marshall: Soldier-Statesman of the American Century and Allies and Adversaries: The Joint Chiefs of Staff, the Grand Alliance, and U.S. Strategy in World War II, for which he was awarded the Distinguished Book Award of the Society for Military History. He was editor of The Papers of George Catlett Marshall, vols. 6 and 7, with Larry I. Bland and Daniel D. Holt.

Related

Staff Sergeant Richard Hobbes and D-Day

Operation Overlord and the 29th Infantry Division

D-Day Plus Six: Marshall in Normandy