In 1938, Brig. Gen. George Marshall was Deputy Chief of Staff of the Army, and Lt. Col. Henry “Hap” Arnold was Assistant Chief of Air Corps. On the face, their jobs appear equal – both second in line – but the Army Air Corps was under the command of the Army, hence the difference in rank. Arnold became Chief of Air Corps in 1938, and Marshall Chief of Staff of the Army in 1939.

While the renamed Army Air Forces was still technically under the Army, President Roosevelt elevated Arnold to a de facto member of the newly organized Joint Chiefs in a speech. As Marshall recounted to his biographer, Dr. Forrest Pogue,

General Arnold was under me because the Air Corps was part of the army, and that would take congressional legislation to change. But when the president came out with this message, in which he referred to his military leadership of myself as chief of staff, of Admiral King as head of the navy, and of General Arnold as head of the Air Corps – we had a separate Air Corps to all intents and purposes – and he matter was settled right then.

The Joint Chiefs enjoying their weekly lunch together.

This led to some frustration on both the part of the Army and the Army Air Forces leadership, as up until this time, the Air Forces had not had its own senior leadership on par with the Army General Headquarters, and in fact was not prepared for the demand on officers. Marshall frequently got irritated and would tell Arnold “I was tired of hearing from that goddamned high school staff he had down there. And he would always take it very well.”

Marshall elaborates on the staffing issues, “I tried to make him as nearly as I could chief of staff of the air without any restraint, though he was my subordinate. And he was very appreciative of this. My main difficulties in the matter came from the fact that he had a very immature staff. They were not immature in years … they were not trained.” Marshall noted that many of the Air Forces officers had not attending Army leadership schools such as Command and General Staff College or the Army War College, to their detriment as they had a steep learning curve.

Marshall and Arnold spent a lot of time together during World War II, and by all accounts, got along very well. Marshall found Arnold very agreeable to work with, and they traveled together extensively, “General Arnold was … my constant companion. I flew pretty much everywhere with him in the United States, and he flew pretty much everywhere with me abroad.” They visited military training and production sites, attended meetings, and overseas conferences.

Watching a tank demonstration. Arnold is left, Marshall is right.

Officers meeting at Marshall’s map table, which is now in the Marshall Foundation Library.

Adm. Ernest King, Marshall, and Arnold leave a meeting at the White House in February 1944.

Arnold had heart problems, suffering four heart attacks during the second half of World War II. He spent time in the hospital, and missed the Yalta Conference after one attack. Marshall urged Arnold more than once to rest and recover so that he could go on serving. In May 1943, Marshall wrote Arnold several times admonishing him: “I want you to be very careful not to worry about our affairs here because if you do that it will mean an indefinite stay in the hospital. We will manage and you devote yourself to yourself.” When he didn’t think Arnold was recuperating carefully enough, he wrote “Get solidly on your feet and absolutely refrain from any inspections, interviews, speeches, or anything in the way of business. It is vastly important to you, and it certainly is to me, and to the Air Forces, that you make a full recovery, and you cannot do it if you overrun your own internal machinery.”

In March 1945, after another heart attack, Marshall counseled Arnold, “Whatever you do now don’t hurry to return here and nullify the advantage you have gained by a real rest. Giles has matters well in hand and there is little you can add to the scenario at the moment. The less you worry about it the better.” When it became obvious that Arnold was not following doctor’s orders but returning to work, Marshall responded with

I am rather depressed at seeing you start on another of your strenuous trips, this time carrying you around the world. It may demonstrate to the Army and to the public that you certainly are not on the retired list but also it may result in your landing there. I will have to trust to your judgment though I have little hope that you can curtail your wasteful expenditure of physical strength and nervous energy.

The men also enjoyed similar hobbies of hunting and fishing, and went as often as their schedules allowed. In November 1942, Marshall and Arnold spent a day duck hunting outside Washington, D.C. In August 1944 while in California, they took an opportunity to go fishing. During a refueling stop in Newfoundland returning from an overseas meeting, the generals went on a very short fishing expedition. Over Thanksgiving weekend 1945, Marshall and Arnold went pheasant hunting in North Dakota just after Marshall left active duty service.

Marshall and Arnold pheasant hunting in North Dakota the week before Marshall left active-duty Army service.

Marshall missed his regular communications with Arnold as he wrote from China in October 1946 to a retired Arnold, who had taken up a second career as a member of the California Fish and Game Commission, “I have lost all contact with you aside from the knowledge that you are Fish and Game Commissioner of California. This one item of information suggests to me glorious fall days in the mountains for fish, and pheasant hunting de luxe. I envy you your freedom.”

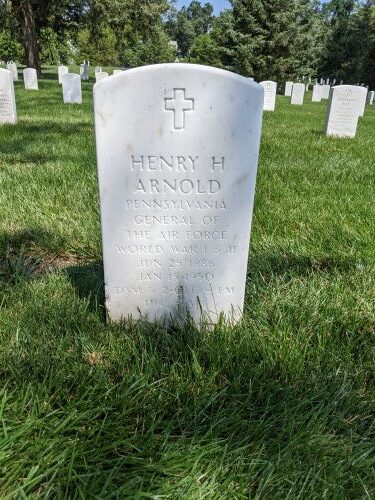

Marshall lost one of his favorite hunting and fishing buddies, and a good friend, on January 15, 1950, from a final heart attack. Marshall attended Arnold’s funeral as an honorary pall bearer at Arlington Cemetery. Robert Lovett, who served as Assistant Secretary of War for Air during the war, commented that Arnold had been a casualty of war just as if he had been in the line of duty.

Gen. Hap Arnold still has the legacy of being the only officer to serve as a five-star general for the Army and the Air Force.

Before becoming director of library and archives at the George C. Marshall Foundation, Melissa was an academic librarian specializing in history. She and her husband, John, have three grown children, and live in Rockbridge County with three large rescue dogs. Melissa is known as the happiest librarian in the world! Keep up with her @MelissasLibrary.