George Marshall’s public stature caused people to think of him as a possible presidential candidate—as early as 1943. He emphatically squashed such speculation, but he could not change the fact that for six months in 1947, he was only a heartbeat away from being president because of the presidential succession law at the time.

In November 1943, Marshall wrote a statement for Henry Stimson, secretary of war, to read at a press conference: “I regret very much the recent references to General Marshall of a political nature. Such discussions cannot be otherwise than harmful to our war effort on which everything must be concentrated. I know they are embarrassing to General Marshall and furthermore, I feel that they make his present task more difficult. I can speak with authority in stating that there has been no discussion of this nature with General Marshall by anyone. Further, that he will never permit himself to be considered as a possible Presidential candidate. His training and ambitions are not political.”

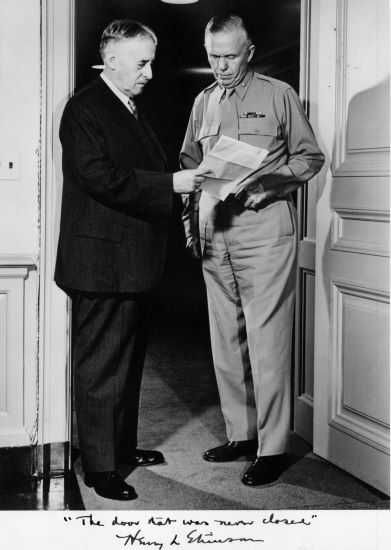

Secretary of War Henry Stimson and Army Chief of Staff George Marshall in the doorway between their offices at the Munitions Building.

A Marshall admirer wrote to Katherine Marshall in May 1946 to tell her of a potential movement to nominate her husband as the Democratic Party’s candidate for president in 1948. Marshall drafted Katherine’s reply: “I can assure you that he has no intention of ever entering into politics, and there is no possibility of his ever changing his mind.”

When Marshall returned from his China mission in January 1947 to become secretary of state, he again issued an emphatic statement that he could not be considered a candidate for public office: “I think this is as good a time as any to terminate speculation about me in a political way.

George Marshall being sworn in as Secretary of State with President Truman looking on.

“I am assuming that the office of Secretary of State, at least under present conditions, is non-political and I am going to govern myself accordingly. I will never become involved in political matters and therefore I cannot be considered a candidate for any political office.

“The popular conception that no matter what a man says he can be drafted as a candidate for some political office would be without any force with regard to me. I cannot be drafted for any political office.

“I am being explicit and emphatic in order to terminate once and for all any discussion of my name with regard to political office.” (Marshall was so apolitical that he followed a common practice among senior U.S. military leaders and did not vote in elections.)

Marshall’s close brush with the presidency came about because of President Franklin Roosevelt’s death on April 12, 1945. Vice President Harry Truman became president, and the office of vice president remained vacant until the next president took office on January 20, 1949. (The 25th Amendment, adopted in 1967, now provides for filling the vice president’s office when it becomes vacant.)

President Harry S. Truman

The Constitution grants Congress the power to establish the order of succession to the presidency when the office of vice president is vacant. In the Presidential Succession Act of 1886, which was in effect in 1947, Congress had stipulated that the next person in line was the secretary of state, followed by other cabinet members, in order of the establishment of their departments. Many national leaders, including Truman, felt that the vice presidency ought to be filled by someone who had been in an elective office instead of an appointed one. Hence, the order was changed by the Presidential Succession Act of 1947, which placed the speaker of the House of Representatives and the president pro tempore of the Senate ahead of the secretary of state. The law became effective on July 1.

If President Truman had died between January 21 (when he became secretary of state) and July 1, 1947, George Marshall would have become president of the United States. That leads to all kinds of speculation about what kind of president he would have been and whether he might have sought a second term if pressured to do so.

Notes:

Tom Bowers is the former docent director at George Marshall’s Dodona Manor in Leesburg, Virginia. He was professor and dean of the School of Journalism and Mass Communication at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill from 1971 to 2006.