George Marshall didn’t grow up around horses. He rode as necessary for Army transport at the turn of 20th century, but he wouldn’t be considered an expert equestrian. Marshall was hampered by a high-school injury to his elbow and didn’t have the range of motion needed to control a horse if it stumbled, so he would never be rated an expert horseman. This was problematic for Marshall;at his first duty station in the Philippines, Marshall’s horse fell on him, injuring his right ankle. The severe sprain required the use of crutches for several weeks and relegated him to duty on post.

Marshall didn’t become an equestrian until he was stationed at Fort Leavenworth, KS, at the School of the Line in 1906. After his two years as a student, Lt. Marshall became an instructor, and had more free time. President Theodore Roosevelt encouraged Army officers to be riders as a way of staying fit, so Marshall took the President’s motivation a bit further – he purchased an untrained horse.

I rode practically every day. I bought a horse and trained it. I wanted to learn how to do that. That required a great deal of time, of course, particularly in the riding hall, which I didn’t like very much. But I undertook to try to train a horse.

When work required staff and students at the school to ride out from the post, those with him knew they could follow Marshall home – he always seemed to know the direct route. One time, the group stopped at a creek in a deep gully. There were two foot-wide planks laid across from one bank to the other for foot traffic, and Marshall confidently rode his horse across the makeshift bridge. None with him followed.

Proficient horsemanship was displayed on a summertime two-week school staff ride through the northern Shenandoah Valley up through Gettysburg, studying the Civil War battles fought in the area.

Horses at the watering trough during the staff ride.

During World War I, Marshall again injured his ankle while riding to view preparation for the attack on Cantigny. A physician bound Marshall’s injured ankle because he wanted to be at the division to oversee the attack that he had planned.

Just at this busy time, my connection with the First Division came very near being terminated, at least temporarily. Coming up out of the Division Headquarters dugout on the late afternoon of the 26th, I got on my horse and started him at a canter up a trail leading from Division Headquarters. In my haste to get under way I had carelessly hurried the horse into a lope before I had adjusted myself in the saddle or straightened out the reins. He slipped, or stumbled, went down, and rolled over twice, my left ankle remaining in the stirrup and sustaining painful fracture. Crawling back on the horse, I returned to Headquarters and was carried down in the dugout. The doctor strapped up my foot with adhesive tape and I continued my participation in the affairs of the division with the injured foot resting on a table or a chair.

Col. George Marshall rides in the Paris victory parade through Paris, 1919. He is on the white horse to the right.

After the war, Marshall rode a white horse in a victory parade through the Arc de Triomphe in Paris in July of 1919, just behind Gen. John Pershing. He also rode in a victory parade in New York City after returning to the States.

Col. George Marshall carrying the general’s flag and riding behind Gen. John Pershing at the New York City victory parade, 1919. Library of Congress photo

Marshall had come to love riding; it was one of his favorite activities. In Aug 1920, he wrote while on a vacation in Lexington, VA: “I have been having a fine holiday, riding three or four hours daily through beautiful country.” He remarked in a speech to the Virginia American Legion, and VMI Club:

I think I have ridden horseback over more of Virginia than probably any of you present here tonight. I have enjoyed and appreciated the country more than those who merely see it from a rapidly moving automobile. The Blue Ridge, the Alleghenies, the Shenandoah and the James River always make a definite picture in my mind.

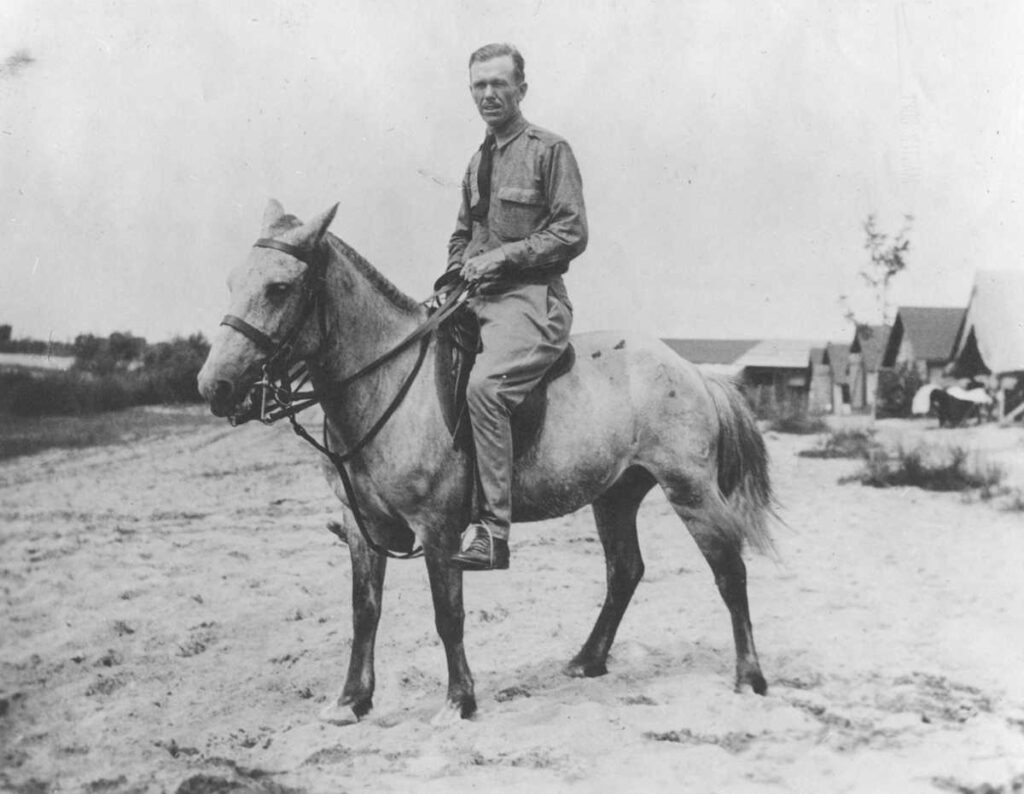

Lt. Col. George Marshall on his Mongolian horse in China, 1926.

He rode a Mongolian horse while serving in China in the mid-20s. He rode while stationed at Fort Benning (now Fort Moore), GA, when he was assistant commandant at the Infantry School. His favorite horse there was Duchess.

Lt. Col. George Marshall with Duchess at Fort Benning (now Fort Moore), GA, in 1928.

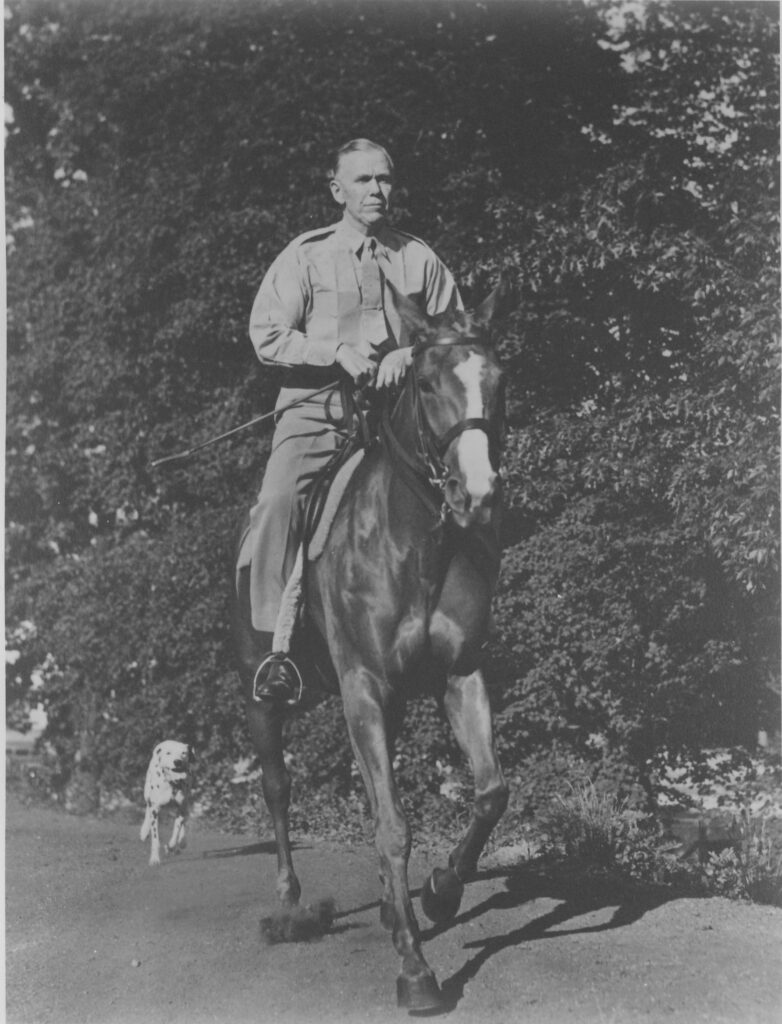

When Marshall moved into Quarters 1 at Fort Myer, VA, a former student from the Infantry School. Gen. Terry Allen, shipped Marshall two horses from Kansas for Marshall to ride. The two horses, Reno Fantas and Prepare, spent many mornings galloping around Fort Myer. Marshall never rode with the men with whom he worked as he didn’t want office talk; one of his frequent companions was fellow equestrian, his stepdaughter, Molly. Marshall was riding Prepare on Dec. 7, 1941, when the phone rang with news of the attack on Pearl Harbor.

Gen. George Marshall riding Prepare with Fleet the dog at Fort Myer, VA, in 1941.

Marshall, with a cavalry troop, led off President Franklin Roosevelt’s inaugural parade down Constitution Avenue in 1941, riding King Story. The next year, the cavalry switched to tanks, but kept a few horses for ceremonial purposes.

Gen. George Marshall leading the 1941 inaugural parade.

After leaving active duty, Marshall enjoyed riding near Front Royal, VA, the former Army Quartermaster Corps Remount Service, where horses and mules had been bred for military service. The Army still had personnel and some horses and mules there, and one of the horses he rode was named Rositta. When Molly was in town, she would join him for a ride. Marshall didn’t keep horses at his home in nearby Leesburg, VA, as the three acres was not big enough and there was no barn.

For Marshall, spending time riding his horses was a healthy break from the demands of his career, especially during World War II — this allowed him to have the reserves of physical and emotional strength to serve two terms as Army chief of staff. He not only encouraged work/life balance among his subordinates, but he also demonstrated it.

Before becoming director of library and archives at the George C. Marshall Foundation, Melissa was an academic librarian specializing in history. She and her husband, John, have three grown children, and live in Rockbridge County with two large rescue dogs. Melissa is known as the happiest librarian in the world! Keep up with her @MelissasLibrary.