In June 1951, news broke that Gen. George C. Marshall was to receive a new puppy from the children of Norway.

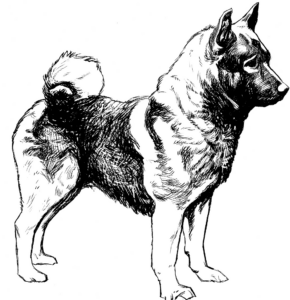

Marshall’s aide, Sergeant C. J. George, informed the General on June 7 that Norwegian youth had begun collecting money for a Norwegian elkhound, a spitz breed prized in the country since medieval times and a national symbol akin to the American bald eagle. Elkhounds are noted for their ability to independently track, hunt, and corner moose, and are considered excellent (if high-maintenance) family pets due to their loyalty and intelligence.

The puppy was an overt gesture of gratitude and goodwill towards Marshall for his advocacy for European recovery, a $13b program popularly referred to as the Marshall Plan that revitalized the economies of western Europe and prevented Soviet dominance over the entire continent. Norwegian schools held an essay contest on the topic of NATO, and the winner had the opportunity to visit the United States and personally present Marshall with the dog.

Thomas White, the secretary-treasurer of the Norwegian Elkhound Association of America, sent Marshall a brochure about the breed and offered any assistance the Marshalls needed “to help you with the puppy.” Marshall replied on July 6:

“Mrs. Marshall and I are looking forward to receiving the Norwegian Elkhound puppy and the brochure which you inclosed [sic] has added considerably to our interest in this breed. Your enthusiasm assures me that we will derive much pleasure from the puppy. We appreciate your offer of assistance and if any unusual traits are noticed I will certainly write you.”

An eighteen-year-old student named Arnt Natland won the essay contest and travelled to Washington, D.C. with the four-month-old puppy, named Nato. Marshall received Nato on July 11 at the Pentagon. During the ceremony, Marshall was impressed by Nato’s good behavior. According to the press, Marshall said “If all the rest of the world were as well-behaved as this young fellow there would be less trouble in the world.”

Gen. Marshall receives Nato from Norwegian student Arnt Natland (right) on August 11, 1950, in front of the Pentagon.

Unfortunately, Nato’s time with the Marshalls was brief. Two months after receiving the dog, Marshall wrote to Thomas White and took him up on his offer:

“We are extremely fond of Nato (which he was christened before he left Norway and the name he still carries), but now find that it is not possible to give him the care that he deserves, the reason being that we spend our winters at Pinehurst, North Carolina, where there are no accommodations for the dog.”

Marshall noted that he was only able to stay at his residence in Pinehurst on weekends, which unfairly put the responsibility of care on his wife, Katherine, for the majority of the time. “Mrs. Marshall and I are very reluctant to give Nato up,” Marshall wrote, “but in fairness to the dog, I think it is best that we do so.”

They placed Nato under the attentive care of Mr. White, but asked that he “keep the matter on a confidential basis,” as Marshall did not “want to do anything that would embarrass or offend those who were so generous in making him available to me.”

Though Nato only stayed with the Marshalls for a few months, his story symbolizes international cooperation and serves as a reminder to appreciate acts of gratitude for the unifying power they hold.

Information for this article was found in The Papers of George Catlett Marshall, vol. 7., edited by Mark A. Stoler and Daniel D. Holt.

Glen Carpenter began working at the George C. Marshall Foundation in 2018. He has a background in American studies (focusing on film, music, aesthetics and twentieth-century consumer culture) and video production. He lives in Roanoke, Virginia.