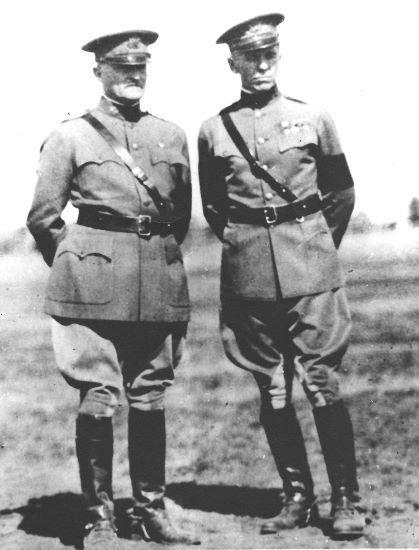

On Oct. 3, 1917, Gen. John Pershing, commander of the American Expeditionary Forces in France during World War I, visited the First Division to see training in trench warfare. Acting Chief of Staff Capt. George Marshall arranged for Maj. Theodore Roosevelt, Jr., to demonstrate a new method for attacking the enemy in their trenches.

Pershing questioned Division Commander Gen. William Sibert about the demonstration afterwards. Sibert didn’t have much to say as he had not seen the method before. Pershing grilled Sibert’s brand-new Chief of Staff, who had arrived two days before, and was met again with hesitant answers. Unhappy, Pershing “just gave everybody hell.” He said that the division was wasting time and not following traditional training methods. Gen. Pershing was accosted by Capt. Marshall, who thought the unit’s members, especially Gen. Sibert, were being treated very unfairly, and Marshall began explaining things. Pershing, in no mood to listen, turned to leave.

Marshall, “mad all over,” put his hand on Pershing’s arm. He began to talk. “General Pershing, there’s something to be said here and I think I should say it because I’ve been here longest.” He unloaded “a torrent of facts” on Pershing. His fellow officers standing nearby “were horrified” and thought Marshall “would be fired right off.”

Marshall realized he had “gotten into it up to my neck.” Pershing, however, listened. After the general left, officers offered their best wishes, to which Marshall replied, “All I can see is that I might get field duty instead of staff duty.”

There was no punishment for what was in fact a court-martial offense on Marshall’s part. Instead, when Pershing visited the First Division over the next several months, he would take Marshall aside and ask him how things really were. In July 1918, Marshall was moved to the General Headquarters to serve as assistant G-3, working in operations, where he further distinguished himself in planning and logistics.

After the war, Marshall became the aide-de-camp to Pershing, and served with him as his closest adviser for the next five years. This began a lifelong mentorship and friendship, with Pershing serving as best man at Marshall’s wedding to Katherine, and Marshall helping Pershing write his memoir. While Chief of Staff, Marshall had a painting of Pershing hanging directly behind his desk.

George Marshall believed honesty was expected of a U.S. Army officer, and during World War I he was gaining the reputation for being a straightforward speaker not intimidated by his audience. Marshall learned from what he saw around him and was always careful to speak privately with an officer or soldier who needed correction. These traits would serve him well in his career.

But speaking plainly would also cause him potential difficulty again.

On November 14, 1938, Brig. Gen. George Marshall, as Assistant Chief of Staff War Plans Division, was one of a dozen, including Secretary of the Treasury Henry Morgenthau, WPA Administrator Harry Hopkins, Assistant Secretary of War Johnson, Solicitor General Robert H. Jackson; and generals Malin Craig and “Hap” Arnold, meeting with President Roosevelt.

During this first meeting at the White House for Marshall, Pres. Roosevelt was strongly encouraging appropriations for airplanes. He wanted to deter any thought of German invasion in North or South America and believed that planes were a better deterrent than a large Army on the ground. Pres. Roosevelt spoke at length, and among the attendees, “most of them agreed with him entirely. He came around to me … and said, ‘Don’t you think so, George?’ I replied, ‘I am sorry, Mr. President, but I don’t agree with that at all.’ The President gave me a started look and when I went out they all bade me good-by and said that my tour in Washington was over.” What Marshall said to the President “didn’t antagonize him at all. Maybe he thought I would tell him the truth so far as I personally was concerned, which I certainly tried to do in all our conversations.”

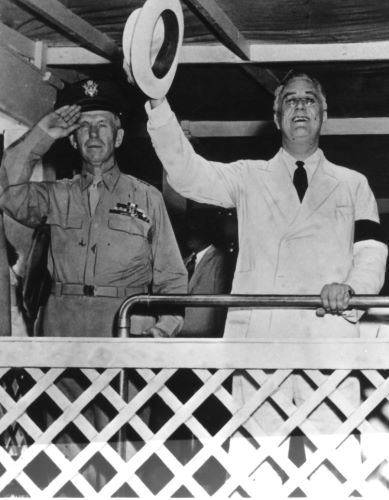

Marshall became a trusted adviser to the President during the war, traveling to units around the world, and to conferences, and bringing to Pres. Roosevelt the clear facts and information he depended on.

Marshall was trusted by both parties in Congress because he always spoke honestly and allied himself with no politics as he worked with them to pass appropriations for men, materiel, and infrastructure necessary to win the war.

In Dec. 1943, at the Cairo Conference, Harry Hopkins was sent as emissary from the President to Marshall to see how Marshall would feel about being Supreme Allied Commander in Europe for the invasion. Marshall sent the message back that he would “go along whole-heartedly with whatever decision the President made.”

Marshall later said that he was “utterly sincere in the desire to avoid what happened so much in other wars – the consideration of the feelings of the individual rather than the good of the country.” Roosevelt replied to Marshall’s comment, “Well I didn’t feel I could sleep at ease if you were out of Washington.”

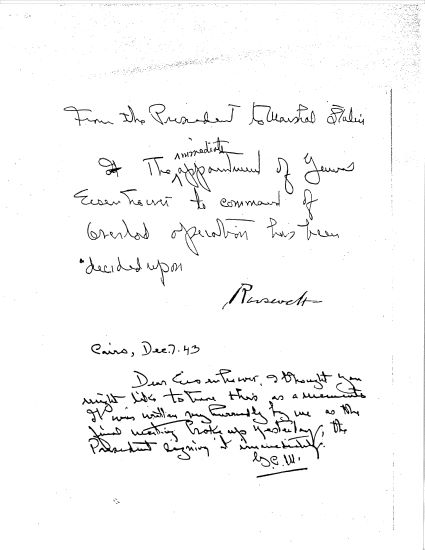

Marshall understood the necessity of the President’s decision, and characteristically wished Gen. Eisenhower well in a handwritten note:

From the President to Marshal Stalin

The immediate appointment of General Eisenhower to command of operation has been decided upon.

Roosevelt

Cairo, Dec. 7 43

Dear Eisenhower. I thought you might like to have this as a memento. It was written very hurriedly by me as the final meeting broke up yesterday, the President signing it immediately.

G. C. M.

George Marshall’s reputation of forthright integrity had many wanting him to run for President after he left military service. Marshall, who was apolitical, declined very honestly.

Quotes from George Marshall in Education of a General and Organizer of Victory, both by Dr. Forrest Pogue.

Melissa has been at GCMF since Fall 2019, and previously was an academic librarian specializing in history. She and her husband, John, have three grown children, and live in Rockbridge County with three large rescue dogs. Keep up with her @life_melissas.