Issues surrounding prisoners of war (POWs) played a critical role in Korean War history. Disagreements between the US-led United Nations Command and the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK)-People’s Republic of China opponents over POW repatriation delayed the armistice by many months. Rumors and unjust insinuations of POW disloyalty tarnished the reputations of many Korean War veterans and prompted the creation of the Code of Conduct in 1955. General George C. Marshall, an important member of the Truman administration during key moments in the war, provided the clearest reflection on the POW issue in a letter he wrote to General William Dean, the war’s most well-known POW, in 1953. Understanding Marshall’s perspective on POWs provides insight into the war and illustrates why POW issues still matter today.

General Dean deployed to Korea as commander of the Twenty-Fourth Infantry Division during the difficult days of early July 1950. At that time, the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea forces defeated the United States and Republic of Korea (ROK) units in their bold gambit to unify the peninsula under the DPRK government. US units were underequipped, understaffed, and undertrained. Later in the month, the Twenty-Fourth Division set up positions near Taejon, an important city on the way to the communications hub at Taegu. As the division began its staged withdrawal, July 20-21, 1950, Dean stayed in the city to support the Thirty-Fourth Infantry Regiment, a unit within the Twenty-Fourth Division. In a move that was both daring and foolish, Dean personally led bazooka teams through the city looking to disable DPRK tanks—a key factor in the early success of the DPRK offensive. This bold move earned Dean the Medal of Honor, but it also cost him dearly. In the midst of the Twenty-Fourth’s fighting withdrawal, Dean was separated from his men and eventually captured.

Like many POWs, Dean suffered at the hands of the enemy. After being captured, he was confined initially to a tiny cell no larger than four square feet. After he took off his boots to soothe his swollen feet, his DPRK captors replaced them with rubber boots without soles. They forced him to march in this substandard footwear, causing great injury to his feet. Next, his DPRK captors subjected Dean to lengthy interrogations, one of which lasted sixty-eight uninterrupted hours. They threatened him with bodily harm, promising at one point to cut out his tongue if he refused to cooperate. Adding further strain, prison officials kept Dean separated from fellow American prisoners during his entire captivity. Despite these pressures, Dean did not break.

When Dean returned home to a hero’s welcome, he told anyone who would listen that other POWs had it much worse. Dean recalled that he had received adequate food during much of his captivity, and after his interrogators realized he had little military intelligence to offer, they began to treat him more humanely. In the first paragraph of his memoir, Dean underscored this point by confessing, “There were heroes in Korea, but I was not one of them.” Dean deeply regretted his capture and found no honor in surviving his time as a POW.

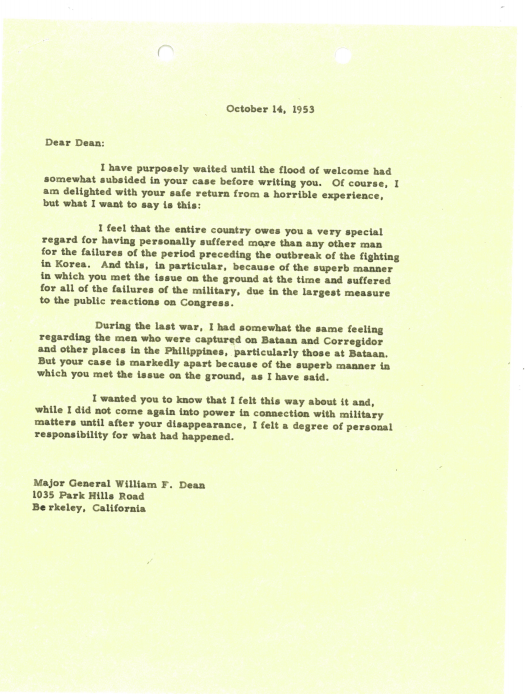

Marshall drew a different lesson from Dean’s harrowing experience. A little after a month following Dean’s return, Marshall wrote a letter praising Dean for the “superb” way in which he fought in Taejon and then resisted his captors’ entreaties to cooperate. Marshall believed he bore some responsibility for the war’s early reverses. Over the course of Korea’s rough transition from colony to independence, Marshall repeatedly dissented against proposals to withdraw US forces from the Korean peninsula. Forrest Pogue observed that Marshall’s “experience in China, with the Russians in Manchuria, and more recently with the Soviets in Germany increased his awareness of the North Korean threat to the South.” Marshall also understood that the administration he served had not adequately prepared the ROK for its independence. This lack of preparation, along with American unpreparedness for war following the rapid post-World War II demobilization, contributed to the disastrous early months of the Korean War.

Marshall’s Letter to Dean, pg. 1

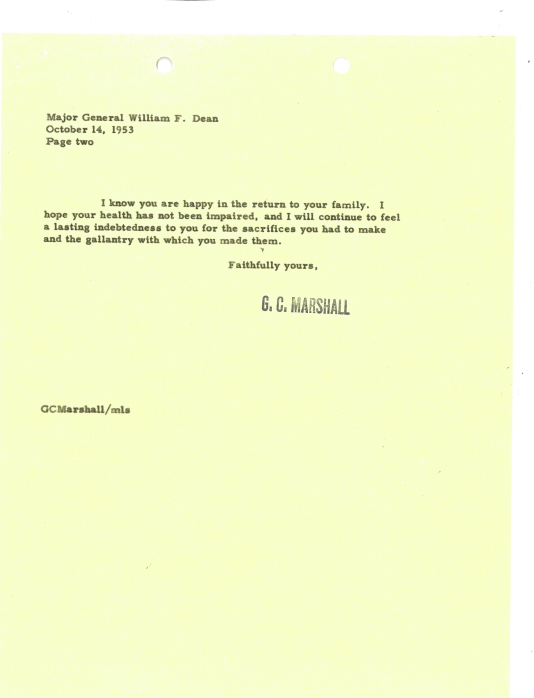

Marshall’s letter to Dean, pg. 2

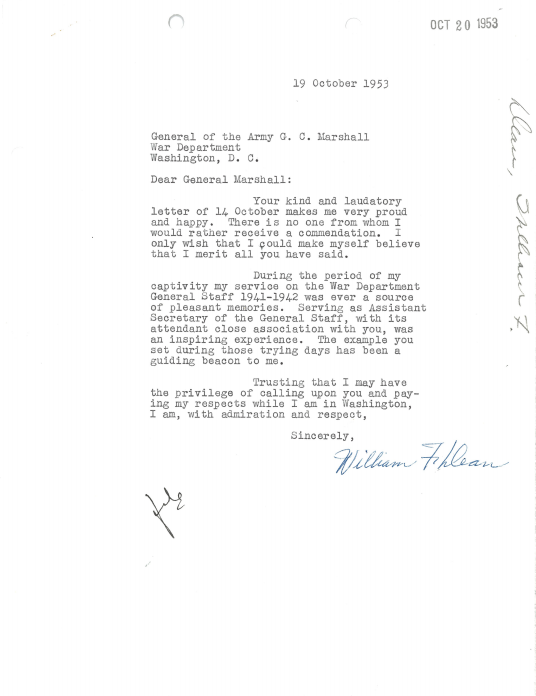

Dean’s reply to Marshall

Beyond the immediate context of the war’s origins and early course, Marshall understood that the United States carried a special obligation to seek the repatriation of American prisoners of war as a matter of national honor. In his conclusion to his note to Dean, Marshall confessed he would “continue to feel a lasting indebtedness to you for the sacrifices you had to make and the gallantry with which you made them.” The desperate fighting during the Korean War and the privations suffered by American POWs meant the United States owed a special debt to those who served in the Korean War.

The same sense of obligation that motivated Marshall’s concluding words energizes the work of the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency (DPAA). A part of the larger Department of Defense, the DPAA utilizes cutting-edge historical research, archaeological methods, and forensic science to locate, identify, and repatriate unaccounted-for remains of servicemen from World War II, the Korean War, the Vietnam War, and later wars. Driven by core values like compassion, integrity, and innovation, the Agency delivers on its mission to “provide for the fullest possible accounting for our missing personnel to their families and the nation.” In this way, the DPAA, its volunteers, and allies pay our debt of gratitude to Korean War veterans and all other veterans. The work of the DPAA team makes certain that the POWs of the Korean War—and other wartime service members who are unaccounted for—will not be forgotten.

Zachary Matusheski PhD, DPAA Historian in Residence, The Ohio State University

Zachary Matusheski PhD, DPAA Historian in Residence, The Ohio State University

Matusheski won a Baruch grant from the George C. Marshall Foundation and also won the John A. Adams ’71 Center for Military History’s Best Unpublished Article Award in 2012 .

Zachary Matusheski is not an employee of DPAA, he supports DPAA through a partnership. The views presented are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of DPAA, DoD or its Components.