On the 64th anniversary of Gen. George C. Marshall’s death, we honor his memory with this wonderful blog written several years ago by former museum curator Cathy DeSilvey.

George C. Marshall Mourned Throughout the Free World

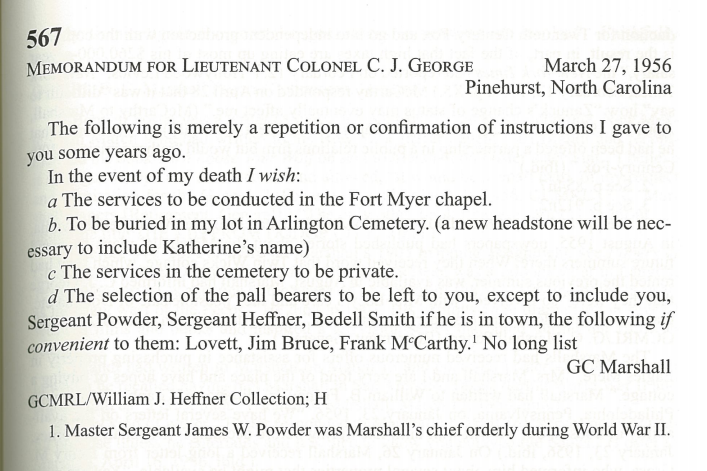

Marshall had planned the state funerals of General John Pershing and President Franklin Roosevelt and could not imagine all of the pomp and circumstance for himself. Dealing with a bout of pneumonia in 1953 on his way to Oslo, Norway, to accept the Nobel Peace Prize, Marshall discussed funeral plans with his assistant, COL C. J. George. COL George warned him that “if he died during the Eisenhower administration he would certainly get the most elaborate funeral possible unless he left definite orders to the contrary.” Three years later he instructed COL George, in writing (below), on instructions for his burial. Marshall did not want to lie in state in the Capital Rotunda, a ceremony at National Cathedral, nor did he want a eulogy.

From The Papers of George C. Marshall Volume 7

General George C. Marshall died on October 16, 1959, at Walter Reed Hospital after a long period of declining health. His service was held at Fort Myer Chapel on October 20, 1959. The graveside service at Arlington National Cemetery was private.

At noon on October 19, 1959, Marshall’s casket arrived at Bethlehem Chapel at Washington National Cathedral to lie in repose for twenty-four hours.

Marshall lies in repose on October 19, 1959. On October 20, his casket was driven to Fort Myer Chapel for his funeral service.

The Armed Forces Honor Guard approaches the Fort Myer Chapel at the start of ceremonies for Marshall’s funeral.

Looking toward the crowd gathered at Fort Myer Chapel.

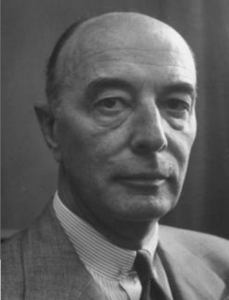

BG Frank McCarthy gathers the pallbearers as General of the Army Omar Bradley walks to his spot.

Honorary pallbearers (14 in all): General of the Army Omar Bradley, M SGT James W. Powder, Robert Woods Bliss, BG Frank McCarthy, unidentified, M SGT William J. Heffner.

Honorary pallbearers (14 in all): (obscured) General Walter Bedell Smith, unidentified, Ambassador James Bruce, Robert A. Lovett, ADM Harold R. Stark, General Lyman L. Lemnitzer.

Marshall’s former Assistant Secretary of Defense Anna Rosenberg arrives at Fort Myer Chapel.

BG Frank McCarthy greets W. Averill Harriman.

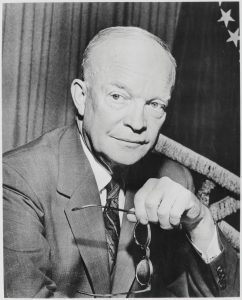

President Eisenhower arrives for the service.

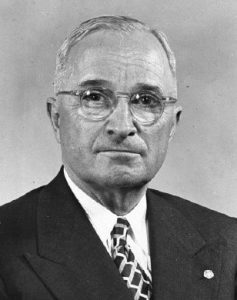

Former President Harry S. Truman, Getty Images. Truman and Eisenhower sat next to each other during the service.

Secretary of State Christian A. Herter attended.

Dean Acheson arrives, at right.

Mrs. Marshall was the last to arrive.

Mrs. Marshall is helped out of her car.

Reverend Franklin Moss, Jr., (clergy, left) of General Marshall’s home church, St. James Episcopal, in Leesburg, Virginia, and Canon Luther D. Miller of the Washington National Cathedral, a long-time friend of General Marshall’s and former Army Chief of Chaplains prepare to escort the casket into the chapel. The Army Band played the “General’s March,” and then the hymn “Faith of Our Fathers” as the casket was taken out of the hearse.

Marshall’s casket arrived on what Forrest Pogue called a “radiant fall day.”

The casket is solemnly escorted into Fort Myer Chapel.

The military canon of the National Cathedral, Luther D. Miller, who had been Marshall’s chaplain in Tientsen, China, in the 1920s and his Chief of Chaplains at the end of the war, was in charge of the service. Miller conducted a brief Episcopal Order for the Burial of the Dead. Knowing that Marshall wanted no eulogy, Canon Miller’s only allusion to the General he had served over the years was in the prayer “take Thy servant George.”

Miller also conducted the Invocation and Benediction at the dedication ceremonies of the George C. Marshall Research Library on May 23, 1964.

Canon Luther D. Miller (pictured during WWII).

Two hundred guests attended the simple 20-minute service at the chapel. Here Maj. Gen. Marshall Carter and Anna Rosenberg stand outside the chapel. Carter later became president of the George C. Marshall Foundation.

Marshall is carried to the resting spot he selected years before, next to the graves of first wife Lily and her mother.

Taps is played.

Katherine Marshall leaves the graveside service.

Marshall’s grave is now surrounded by many of those who called themselves “Marshall’s Men.”

A sea of flowers at his final resting place.

Dr. Forrest C. Pogue leaves a wreath at Marshall’s grave, date unknown.

The simple epitaph of George C. Marshall.

Upon hearing of Marshall’s death former President Truman stated:

Honor has no modifying adjectives. A man has it or he hasn’t. General Marshall had it. Truth has no qualifying words to be attached to it. A man either tells the truth or he doesn’t. General Marshall was the exemplification of a man of truth. Ability can be qualified. Some of us have a little of it and many have moderate ability, some men have it to the extreme. General Marshall was a man of the greatest ability … He was a man of honor, a man of truth, and a man of greatest ability. He was the greatest of the great in our time. I sincerely hope that when it comes my time to cross the great river, General Marshall will place me on his staff so that I may try to do for him what he did for me.

President Truman’s most important tribute was the 1953 establishment of the George C. Marshall Research Library, which holds the George C. Marshall Archive Collection and the George C. Marshall Museum Collection.

On September 8, 1960, Eisenhower and Marshall’s widow, Katherine attended the dedication of the Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama and unveiled a bust of Marshall. On the occasion Eisenhower said:

On September 8, 1960, Eisenhower and Marshall’s widow, Katherine attended the dedication of the Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama and unveiled a bust of Marshall. On the occasion Eisenhower said:

First of all, he was selfless. Secondly, he was a great student. Third, he had great self-confidence in his judgment of people and sometimes he had a rather odd way of deciding upon this competence. One of them was, he liked them to speak up their own minds in his presence.

I think of course, he (had) moral courage—that includes his readiness always to take responsibility for his own decisions and his own actions. He could not abide, people that were either afraid to make their own decisions, or the fellow that was careless in security.

After Marshall’s death, Churchill said in tribute:

After Marshall’s death, Churchill said in tribute:

Succeeding generations must not be allowed to forget his achievements and his example.

At the dedication ceremonies of the George C. Marshall Research Library, the Honorable Robert A. Lovett said in his remarks:

At the dedication ceremonies of the George C. Marshall Research Library, the Honorable Robert A. Lovett said in his remarks:

I was happily aware that his greatness was indeed enriched by rare personal traits. I noted that he had reverence for the great tradition of the past yet felt no fear of change or of the future. He was a man of extraordinary compassion, of most sensitive and discriminating instinct, and was completely without affectation. There was an air of natural elegance about him which was unassuming and a quality which Dean Acheson correctly identified when he wrote: “The moment he entered a room, everyone in it felt his presence. It was a striking and communicated force.”

Until the day I die I will never cease to marvel how, under almost unbelievable pressures and strain, General Marshall remained steadfast and unchanging—a warm-hearted, considerate, generous, and modest man who reached the heights of greatness without losing his sense of being, first and always, a private citizen in the service of his country.

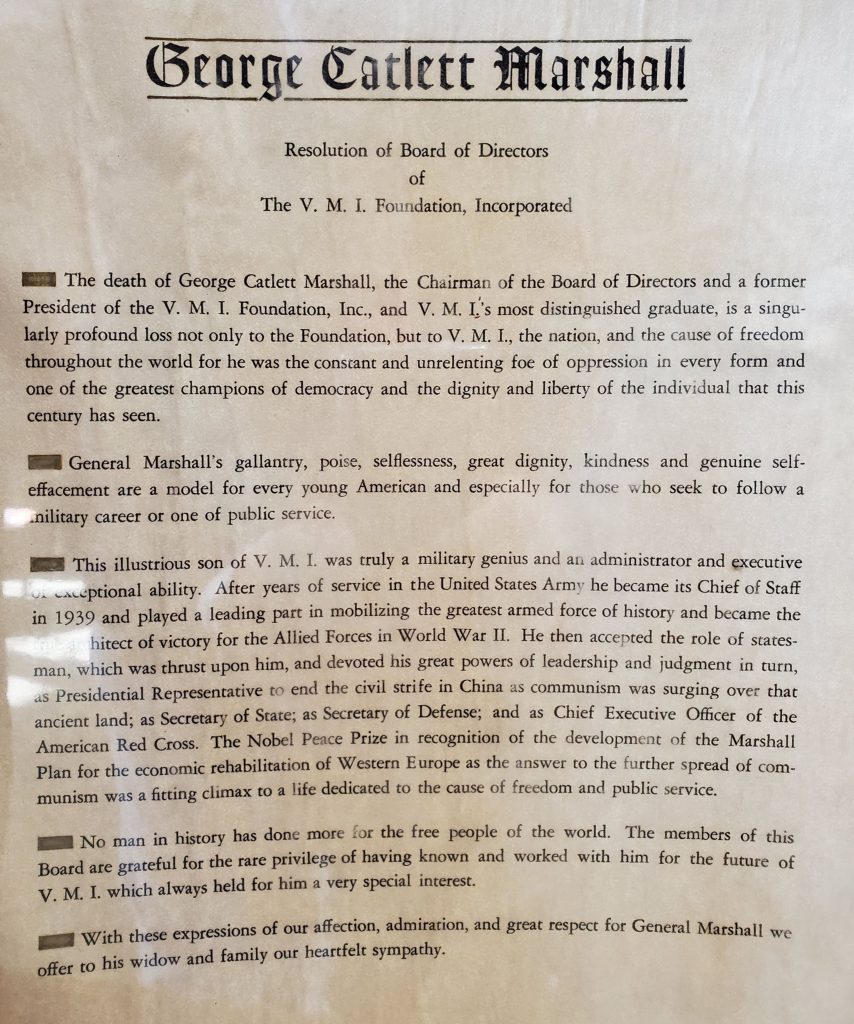

Resolution from Virginia Military Institute’s Board of Directors

Resolution from the American Legion

For a complete and detailed description of his funeral, please visit The Last Salute Civil and Military Funeral, 1921-1969.