Gen. Marshall, Col. Carter, and a Korean American Hero of World War II

by Robert Kim

Robert Kim (right) in Liuzhou, Guangxi Province, August 17 or 18 1945, preparing for take-off with Lt. Robert Peaslee.

The sudden end to the war gave U.S. forces in China a new first priority: liberating and caring for thousands of Allied civilians and POWs. Incredibly, Colonel Marshall Carter had exactly the right man for the mission to Shanghai in the G-5 staff.

In August 1945, Colonel Marshall S. Carter—future Lieutenant General, Director of the National Security Agency, and president of the George C. Marshall Foundation—put his reputation on the line to send a foreign national enlisted man named Peter Kim as the official representative of the Supreme Allied Commander in China on a mission to liberate more than 7,000 American and Allied civilians held captive in Shanghai. In the following year, General George C. Marshall and Colonel Carter worked together to ensure that the U.S. government properly rewarded Peter Kim for his role in this mission. Their actions, unknown to the public for the past 80 years, reveal much about the character of Marshall and of the first leader of the institution that preserves his legacy.

Marshall Carter

Colonel Marshall S. Carter was on his way to the Army’s general officer ranks in 1945. The son of Brigadier General Clifton Carter, he had graduated from the United States Military Academy in the Class of 1931. After the United States entered the Second World War, Major Carter was assigned to the War Department General Staff’s Operations and Plans Division (OPD), created in March 1942 to serve as Army Chief of Staff General George C. Marshall’s staff for planning and directing the execution of military operations. In 1945, as the war in Europe ended and Japan became the primary target of Army operations, now-Colonel Carter and other officers from OPD were sent to China to serve in senior staff positions under the commander of the U.S. Forces, China Theater, Lieutenant General Albert Wedemeyer.

In July 1945, Colonel Carter became the chief of staff to G-5 Civil Affairs commander Brigadier General George Olmsted, whose responsibilities went far beyond those of G-5 sections in other theaters. In addition to normal Civil Affairs duties of working with the government and civilian population of the host country, the G-5 in the China Theater administered Lend-Lease military aid, oversaw economic assistance, procured supplies from the local economy, and had a Clandestine Branch that coordinated U.S., Chinese, and Allied intelligence activities.

Brigadier General Olmsted was well suited for this broad range of responsibilities. A 1922 graduate of the United States Military Academy who had been First Captain of the Corps of Cadets, Olmsted had built a successful insurance business before returning to active duty in January 1942. The Army put him in charge of administering Lend-Lease assistance, and his successful management of this strategically important program led to his promotion to brigadier general and assignment to the G-5 in China. After the war he would further expand his financial businesses and found the Olmsted Scholars Program, which funds graduate study in foreign countries for outstanding young military officers.

The Emperor of Japan’s announcement of his intent to surrender on August 15, 1945, a cause for celebration around the world, created a state of emergency for the U.S. forces in China and the G-5 section in particular. The sudden end to the war gave U.S. military and intelligence organizations in China a new first priority: liberating and caring for the thousands of Americans and Allied nationals in Japanese prisoner of war and civilian internment camps. The G-5 section, with its wide-ranging responsibilities for civil affairs, logistics, and intelligence, would play a key part in planning and organizing the rescue operations.

On August 13, the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) headquarters in Chungking had laid out an array of operations across Japanese-occupied territory on the mainland of Asia, giving each a bird code name: Peking (Magpie), Harbin (Flamingo), Mukden (Cardinal), the Shandong Peninsula (Duck), Shanghai (Sparrow), Hainan Island (Pigeon), Formosa (Canary), Seoul (Eagle), Hanoi (Quail), and Vientiane (Raven). General Wedemeyer made the OSS responsible for the operations north of the Yellow River and assigned those from Shanghai south to French Indochina to the Air Ground Aid Section (AGAS), an intelligence organization that was responsible for rescuing airmen lost behind Japanese lines. The OSS and AGAS began organizing joint task forces, drawn from every U.S. intelligence organization in China, that would parachute or air-land into enemy-controlled cities and demand that Japanese authorities hand over control of their POW and civilian internment camps.

The mission to Shanghai, Operation Sparrow, faced an especially daunting task. More than 10,000 British, Americans, and citizens of other Allied nations had been living in the Shanghai International Settlement when Japanese forces seized it on December 8, 1941. Some 7,000 remained in August 1945, confined in internment camps scattered throughout the city. Unknown numbers of POWs were believed to be there as well. In a metropolis of nine million people where food supplies were running low, there was the risk of starvation. Bloodshed was possible if the thousands of Japanese troops in the city included fanatics wanting to stop a small U.S. force intruding into their conquered territory before the formal end of hostilities.

Incredibly, General Olmsted and Colonel Carter had exactly the right man for the mission to Shanghai in the G-5 staff. He was Peter Kim, a foreign national enlisted man who had joined the U.S. Army in China after years of defending the American community in Japanese-occupied Shanghai.

Peter Kim

Peter Kim was born in 1912 in Pyongyang to a family of early Korean Christians who yearned to go to America to escape the Empire of Japan, which had annexed Korea in 1910. They had lived in the U.S. from 1920 to 1926 while his father, one of Korea’s first medical doctors, pursued graduate medical and public health studies at Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia and Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore. Forced to leave by the restrictive quotas imposed by the Immigration Act of 1924, they had settled in Shanghai, where they could live as part of the international city’s American community. He became the head of the family after his father died in New York in 1934, stranding him, his five siblings, and their mother in Shanghai.

Peter Kim became a steadfast defender of Shanghai’s American community as the Empire of Japan conquered the city. In 1932-38 he served as a rifleman in the American Company of the Shanghai Volunteer Corps, the paramilitary force of the Shanghai International Settlement, which defended the perimeter of the International Settlement while Japanese forces invaded China and occupied the rest of the city in 1937. When Japan took over the International Settlement immediately following the attack on Pearl Harbor, Peter Kim aided American civilians and POWs as a relief worker with the American Association of Shanghai, which then entrusted him with organizing an exchange of American civilians in Shanghai for Japanese civilians that the U.S. and Japan had agreed to conduct. Working with the consulate of neutral Switzerland, he organized the evacuation of 639 U.S. citizens on the U.S.-chartered Swedish passenger liner MS Gripsholm in July 1942.

After Japanese authorities herded citizens of the Allied nations into internment camps in January-March 1943, Peter Kim became the lifeline to the outside world for the interned Americans. Now working for the Swiss Consulate, he delivered Red Cross relief supplies to the internment camps and monitored Japanese treatment of Americans for reporting to the U.S. Department of State. When the U.S. and Japan agreed on a second exchange of American civilians in Shanghai for Japanese civilians in the U.S., he again organized the selection and evacuation process, overseeing the release of more than 900 Americans for repatriation on the Gripsholm in September 1943.

The Kempeitai—the Gestapo of the Empire of Japan—arrested Peter Kim soon afterward in October 1943, detaining and torturing him for 10 days in an attempt to make him into a collaborator. Instead he resigned his position at the Swiss Consulate and planned to escape from Shanghai and make his way to free China to join the U.S. Army. In May 1944, he left Shanghai with his younger brother Richard, and after a six-week long journey on a Japanese-controlled railroad, a Chinese smuggler’s riverboat, and trains packed with refugees, they reached the U.S. forward airbase in Kweilin.

Private Peter Kim, with JICA, during movement between Chungking and Kunming in December 1944. Marshall Foundation photo.

Recruited by the Army’s Military Intelligence Service (MIS), but ineligible to be commissioned since he was not a U.S. citizen, Peter Kim enlisted as a Private in September 1944. He immediately became the MIS’s leading expert on Shanghai and other Japanese-occupied areas of China. Assigned to the Joint Intelligence Collection Agency (JICA), he was repeatedly detailed to other intelligence organizations in need of his expertise. An assignment to the Services of Supply (SOS) in February 1945 brought Private First Class Kim to the attention of an officer on the G-5 staff, Lieutenant Robert Peaslee, who convinced him to request a transfer to the G-5 and urged his superiors to take on this Asian enlisted man who was overqualified for his rank and seemed unmistakably American.

In July 1945, Peter Kim received orders officially transferring him from JICA to the G-5 and reported for duty only a few days after the arrival of Colonel Carter. Promoted to Technician Fifth Grade (Tec 5 or T/5), a Second World War-era rank equivalent to corporal, T/5 Kim continued an independent project that his previous commanding officer in the SOS had allowed him to start on his own initiative in addition to his main duties: collecting and analyzing information on the civilian internment camps in Shanghai. Drawing on his own memories and newly collected intelligence, he prepared reports on the locations of the camps, the numbers of people in them, and the assistance that would be necessary to keep the thousands of internees alive and healthy. One day, he hoped, his efforts would help to save American lives in Shanghai.

Brigadier General Olmsted understood the value of the unusual enlisted man that the fortunes of war had sent his way and made him an extraordinary promise. Olmsted promised that when the time finally came for U.S. forces to launch a rescue mission to Shanghai, he would find a way for T/5 Kim to go on it as one of its leaders.

PFC Peter Kim (middle row, right) and Pvt. Richard Kim (middle row, left) with SOS staff, including Col. Burton Vaughn (back row, third from left) and Lt. Robert Peaslee (middle row, center).

He was a common soldier and not even a U.S. citizen, and if anything were to go wrong during the mission, the entire China Theater headquarters could be subjected to severe criticism for making him an officer and giving him such great responsibility.

Preparing for Operation Sparrow

That time came less than a month later. On August 13, 1945, the order to prepare the rescue mission to Shanghai was issued, and a race began to organize a joint task force for Operation Sparrow. A team was hastily assembling at the U.S. air base in Kunming, four hundred miles from China Theater headquarters in Chungking, and preparing to take off as soon as possible. General Olmsted and Colonel Carter had to act quickly to secure a place for Peter Kim on it.

He had to wait as his intelligence reports on the Shanghai internment camps were taken away to plan Operation Sparrow, and talk about the upcoming missions buzzed around the headquarters. On August 14, unable to wait any longer, he stormed into General Olmsted’s office to demand to know what was happening, interrupting a meeting with a room full of senior officers. Carter calmly told everyone in the room that there was an important matter to discuss with the Tec 5, and Olmsted phoned the head of the G-5’s Clandestine Branch and ordered him to have Kim review the Operation Sparrow plan before its final approval.

T/5 Kim immediately showed that General Olmsted had made the right decision. He found that the plan did not fully leverage the Swiss Consul in Shanghai, his former employer, who was outside of the perspective of U.S. military and intelligence officers in Chungking. The consul, Emile Fontanel, had for years represented the U.S. government in looking after American citizens in Shanghai and could serve as an effective intermediary in dealing with Japanese authorities in the city. T/5 Kim recommended that the Department of State ask the Swiss Foreign Ministry to advise its consul in Shanghai to expect the arrival of a U.S. humanitarian rescue mission and bear witness to any Japanese mistreatment of it. Knowing that Fontanel was a stickler for protocol, he further advised that the mission bear credentials from the U.S. Ambassador to China to present to the consul upon arrival.

The next morning, General Wedemeyer’s Deputy Chief of Staff, Brigadier General Paul Caraway—a colleague of Colonel Carter on the OPD staff before 1945—sent an order that seemed to fly in the face of basic U.S. laws and military regulations. Peter Kim would have to go on Operation Sparrow as an officer and was to be immediately commissioned as a First Lieutenant in the U.S. Army. Since there was no time for a formal commissioning process before the start of the mission, he should immediately pin on lieutenant’s bars and submit paperwork for a direct commission, the details of which could be worked out later.

General Olmsted and Colonel Carter knew that Peter Kim was not a U.S. citizen and that citizenship was a basic statutory requirement for commissioning. An exception was possible if the Secretary of War issued a waiver of the citizenship requirement, but there was not the slightest possibility of obtaining one in the final hours before the start of Operation Sparrow. Olmsted and Carter may have remained silent about this problem when they received Caraway’s order, which had been hastily issued under extreme time pressure. Or they may have been the instigators of the order, who asked Caraway to issue it, with or without telling him about Peter Kim’s citizenship status. Which course of events actually occurred may never be known.

T/5 Kim had his orders, and although he knew that they were legally flawed and stated his objections to them, there was no time to waste. He filled out the commissioning papers, and on August 15, 1945, he became First Lieutenant Kim. His silver lieutenant’s bars were a gift from now-Captain Robert Peaslee, who no longer needed them. He tried to hurry to the airfield to catch a flight to Kunming but was ordered to report to headquarters again, this time to Colonel Carter’s office.

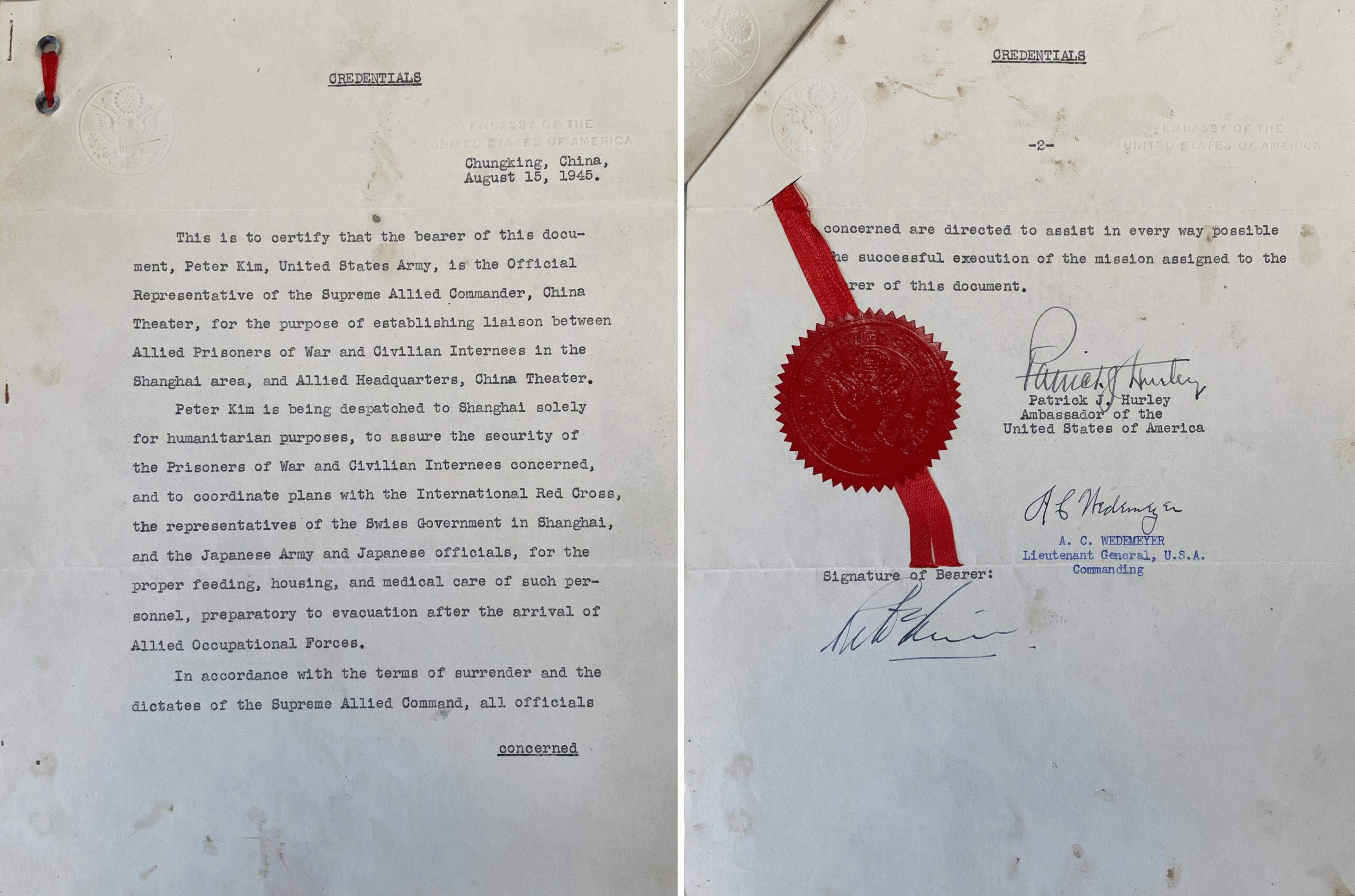

Colonel Carter and Counselor Ellis Briggs from the U.S. Embassy in Chungking were waiting for him there. Briggs presented the newly commissioned lieutenant with a two-page document tied together with a red ribbon, bearing a red wax Seal of the United States. The papers were the diplomatic credentials that he had recommended for the mission, declaring that “the bearer of this document, Peter Kim, United States Army, is the Official Representative of the Supreme Allied Commander, China Theater” and bearing the signatures of U.S. Ambassador to China Patrick Hurley and the Supreme Allied Commander for the China Theater, General Wedemeyer.

When he saw the papers and the authority that they were bestowing on him, Peter Kim’s reaction was disbelief, and he finally let out the misgivings that had been building about his rapidly developing role in the mission. He was a common soldier and not even a U.S. citizen, and if anything were to go wrong during the mission, the entire China Theater headquarters could be subjected to severe criticism for making him an officer and giving him such great responsibility. When Counselor Briggs declared that they would have to take back the credentials and have them re-issued to someone else, Colonel Carter responded that Lieutenant Kim’s lifetime of experience in Shanghai made him the only person competent to serve in such an important role and ordered him to sign the credentials. In this way, Peter Kim became the Official Representative of the Supreme Allied Commander in Shanghai. He then hurried to the airfield to join a group of OSS and AGAS operators who were about to board a C-47 for the flight to Kunming to join Operation Sparrow.

At the same time, unknown to anyone in Chungking or Kunming, Peter Kim’s recommendations on the day before were paving the way for the mission to succeed. In the morning of August 15, 1945, before the noon radio broadcast of Emperor Hirohito’s surrender announcement, Consul Fontanel had summoned the Japanese commandants of the internment camps to a meeting. He told them that the war was over, Japanese authority over the camps would cease at noon, and a U.S. Army humanitarian mission would arrive soon to establish liaison between the camps and the U.S. forces in China.

Operation Sparrow

Peter Kim and Chinese civilian adviser John Lee at Liuchow airfield, morning of August 19, 1945. GCMF photo.

Lieutenant Kim became part of the Operation Sparrow team of just ten men: six officers, two enlisted men, and two Chinese civilian advisors. Led by Major Preston Schoyer of AGAS, they were going to fly in two C-46 Commando transports, unarmed and without any fighter escort, from Kunming to Shanghai, 1,200 miles away. The plan was to try to land at one of Shanghai’s Japanese-controlled airfields and persuade Japanese military commanders to give them access to the internment camps. With only a single jeep loaded into their aircraft for transportation on the ground, they would even have to beg the Japanese for rides through the city. Without Japanese cooperation, the mission would go nowhere, or worse, would be dead on arrival.

Operation Sparrow launched from Kunming in the evening of August 17, landed for an overnight refueling stop at a U.S. airbase in Luliang, and then flew to another forward airbase in Liuchow. There, in the middle of the night, a radio message from Chungking informed them of the Swiss Consul’s proclamations to Japan’s military commanders in Shanghai about their mission. In the morning of August 19, they took off for the final flight to Shanghai, 880 miles away.

As the aircraft neared Shanghai, the pilot of the lead aircraft called Lieutenant Kim into the cockpit to help navigate over his home city to find a suitable airfield. The first turned out to be an unimproved dirt field without the concrete runway that the heavy C-46s would need, and the next two were lined with Japanese military aircraft and swarming with what looked like hundreds of soldiers milling about. The fourth had a concrete runway and only a few small planes and military personnel visible, so the risks there looked acceptable. The pilot made a routine landing on this airfield at 1515, and the other C-46 followed a few minutes later.

Peter Kim with Major Preston Schoyer (second from left) in a C-46 en route to Shanghai, August 19, 1945. Photo recently donated to the Marshall Foundation.

Japanese officers who met them on the airfield turned out to be confused by the arrival of an American military force which no one in their chain of command had to told them to expect. Uncertain of what to do but cooperative, the lieutenant colonel in charge ordered his soldiers to load the Americans’ gear and relief supplies into trucks and request permission to take them to the Swiss Consulate. The late arrival of the airbase’s commanding officer—a colonel who had been drinking away the shame of defeat—brought cooperation to a halt. The colonel threatened the Americans and their Chinese interpreter and ordered them to be taken to the Kempeitai.

The convoy of Japanese military trucks and a jeep took the Operation Sparrow team on a ride in the dark of night through Shanghai, into a comedy of errors that ended at the refuge of the Swiss Consulate. First a column of Japanese army vehicles crossed paths with their convoy, and sober staff officers dismissed the drunk colonel and ordered the convoy to follow them to their headquarters. Then a group of Japanese consular officials and military officers, fully informed about the U.S. relief mission, intercepted them and redirected them to the Swiss Consulate.

Operation Sparrow arrived at the Swiss Consulate at 1900, and Consul Emil Fontanel took the team into the protection of his official residence, inviolable under international law. Peter Kim, unexpectedly appearing wearing the uniform and insignia of a U.S. Army lieutenant, received the most enthusiastic greeting of all from Fontanel and his staff, who had last seen him more than a year earlier and had not known whether he was dead or alive. The next morning, Fontanel hosted negotiations between the U.S. and Japanese sides across his dining table, and terms for entering the camps and for U.S.-Japanese cooperation were worked out.

On August 21, the Operation Sparrow team—now designated the American Military Relief Mission to Shanghai—rode Japanese military trucks and cars into the Chapei and Lincoln Avenue internment camps. They held more than 1,300 interned civilians and a lone POW, a U.S. Marine private who had been captured on the first day of the war while serving with the Marine detachment guarding the U.S. Embassy in Peking. Over the next three days, the relief mission liberated the remainder of the internment camps and inspected Shanghai’s hospitals, which held more than 200 patients from the camps and four more POWs who had been captured on Wake Island in December 1941.

In the afternoon of August 24, the American Military Relief Mission organized the vast array of tasks that had to be done to assist the people in the liberated internment camps until U.S. forces arrived. Peter Kim’s primary task was to restore to them the homes and property that the Japanese had taken from them years earlier. It was a race against time as anarchy was taking over Shanghai, with Japanese military officers and civilian officials plundering the houses that they were going to abandon and mobs of Chinese civilians starting to steal what remained and squat in abandoned properties.

With the authority conferred by his credentials as the Official Representative of the Supreme Allied Commander, Peter Kim negotiated with Japanese officials to establish the process for identifying and returning properties stolen by the Japanese. The negotiations went on for days until a final agreement was concluded on August 27. The agreement required Peter Kim to work with a Japanese commission to confirm the rightful owners and occupants of properties and issue certificates authorizing the reoccupation of former homes.

Then began the immense task of receiving and sorting through the claims of hundreds of Americans and thousands of British and other Allied nationals. It started with an August 28 meeting to discuss the arrangements with representatives from each camp and continued into September. Peter Kim’s personal knowledge of Americans in the internment camps made possible the rapid handling and acceptance of their claims.

After the formal surrender of Japan on September 2, the G-5 staff joined Peter Kim in Shanghai. A team of G-5 officers led by Captain Peaslee arrived on September 8 to take over the administration of electric power, water, the telephone network, and other essential services. Peaslee and Kim worked side by side to ensure the well-being of Americans and people of all nationalities in Shanghai as U.S. and Nationalist Chinese forces took over the city from the surrendering Japanese.

Carter maintained for the rest of his life that Marshall had personally approved of commissioning Peter Kim as an officer in the U.S. Army.

Col. Carter Campaigns for Kim

After V-J Day, General Olmsted and Colonel Carter set out to secure for Peter Kim a reward commensurate to his extraordinary contributions to the successful planning and execution of Operation Sparrow: American citizenship. With Nationalist China asserting full sovereignty over postwar Shanghai, the international communities were leaving the city. In a cruel irony, Lieutenant Kim was administering the program to repatriate U.S. citizens, as a special military assistant to the newly arrived U.S. Consul General, but was himself stuck in China. Olmsted and Carter refused to leave him behind and resolved to right this wrong in the only legally possible way: lobbying Congress to pass a private law for his naturalization.

Olmsted and Carter mustered all of the resources available to them in China to send to Washington. They secured General Wedemeyer’s written endorsement, lending the weight of the Supreme Allied Commander’s name to the campaign. Moreover, they had Captain Peaslee to send as an envoy. From a Minnesota family prominent in the state’s Republican Party, Peaslee was personally connected to Senator Joseph Ball, who was known to be concerned with the problems of displaced persons that the war had created in Europe and Asia. Peaslee secured a meeting with Ball to present Peter Kim’s case during his return stateside for demobilization in late October 1945. Peaslee’s telling of the story and the endorsements of senior Army officers in China were persuasive, and Ball introduced a Senate bill for the naturalization of Peter Kim on November 19, 1945.

Colonel Carter arrived in Washington for his next military assignment in early 1946 and took over what Peaslee had begun. General George C. Marshall, sent to China by President Truman as a special envoy in December 1945, needed an officer with substantial experience in China to serve as his aide and had chosen Carter. Carter served at first as Assistant Executive to the Assistant Secretary of War, then in April 1946 was formally appointed as Marshall’s Special Representative in Washington. He used his posting to the nation’s capital to become a regular presence in Joseph Ball’s office, meeting the senator periodically to provide and receive updates during the lengthy process of moving the bill for Peter Kim through the legislative process.

George C. Marshall and Peter Kim

Colonel Carter’s presence in Washington immediately became crucial to resolving a crisis for Peter Kim in Shanghai. The hurried order to make him a First Lieutenant in August 1945 had left him still officially an enlisted man, and after the efforts of his superiors in China to secure a formal commission for him failed, he was ordered to revert to the enlisted ranks in January 1946. Carter used his access to the highest-level officials in the Pentagon to present Peter Kim’s case directly to those who could do something about it. They included his new boss, the Assistant Secretary of War, and his future one, General George C. Marshall.

There are no surviving official records of what Carter said to Marshall or what Marshall did in response, but Carter maintained for the rest of his life that Marshall had personally approved of commissioning Peter Kim as an officer in the U.S. Army. This version of events is consistent with the final result. The War Department approved waiving the U.S. citizenship requirement in Peter Kim’s case, and in February 1946, he was formally commissioned as a Second Lieutenant.

Lieutenant Kim continued to serve in Shanghai as Senator Ball moved his bill through Congress in the summer of 1946. In June the bill finally made it out of the Senate Committee on Immigration for a vote on the floor of the Senate. In July Ball found a fellow Minnesota Republican willing to introduce the legislation in the House of Representatives, Rep. Walter Judd. Colonel Carter, now Marshall’s Special Representative in Washington, again secured the general’s support at a critical juncture. According to Carter, Marshall personally approved State Department approval of the bill, ensuring that the executive branch would not oppose it.

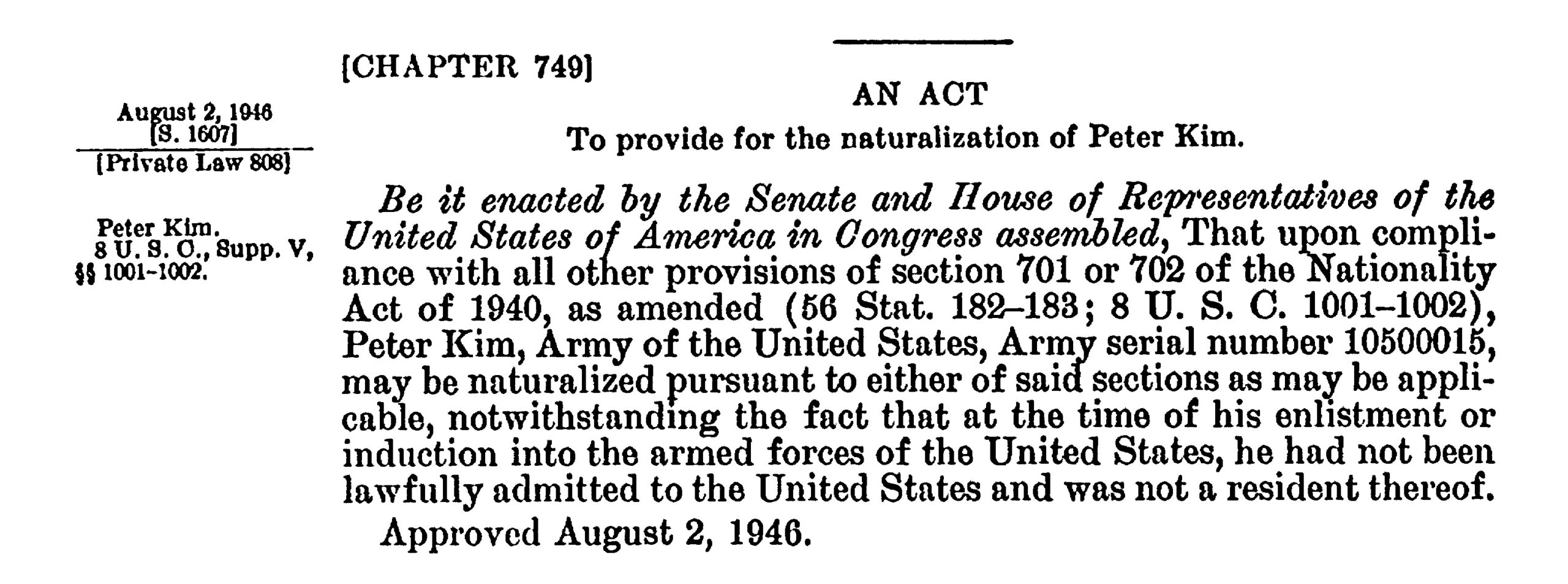

The Senate passed the bill on July 17 as Private Law 808, An Act to Provide for the Naturalization of Peter Kim. President Truman signed the act into law on August 2, 1946.

Peter Kim finally became a U.S. citizen when he swore the oath of allegiance to the United States on December 4, 1946. On June 30, 1947, he finally left Shanghai to return to American soil for the first time in 21 years, now as a U.S. citizen and an officer in the U.S. Army.

Gen. Marshall, Gen. Carter, and Lt. Kim

Peter Kim lived up to Marshall Carter’s belief in him with a 20-year career in the Army that included serving in the Korean War as an intelligence officer in 1950-52 and as Director of the Special Projects and Analysis Division at the Army Language School in the early 1960s, retiring as a Major in 1964. He and Marshall Carter became lifelong friends, the vast differences in their origins, their lives before their paths crossed in 1945, and their ranks in the Army meaning little to either man, who had each seen the other’s true character during the tumultuous final days of the war in August 1945.

When the newly retired Lieutenant General Carter became president of the George C. Marshall Foundation after a distinguished career in which he had served as Deputy Director of Central Intelligence in 1962-65, including as Acting Director of Central Intelligence during the Cuban Missile Crisis, and Director of the National Security Agency in 1965-69, one of the first persons whom he asked to donate their personal papers to the foundation’s archives was Peter Kim. Carter considered his friend’s story to be inextricably connected to his own and to the legacy of George C. Marshall, who in 1946 had quietly intervened to ensure that the U.S. Army and the nation recognized and rewarded Peter Kim’s wartime actions.

At Marshall Carter’s request, Peter Kim began donating his personal papers to the George C. Marshall Foundation archives in 1971. The first items that he donated were the credentials issued to him for Operation Sparrow that designed him the Official Representative of the Supreme Allied Commander, China Theater, and the citation for his wife Ruth’s Presidential Medal of Freedom, awarded for her clandestine work for U.S. Army intelligence in Shanghai in 1944. Completed in 1986, the Peter Kim Papers are a memorial to a remarkable life and a unique journey to America during the Second World War era.

The Peter Kim Papers’ presence in the George C. Marshall Foundation archives is also a testament to a little-known aspect of the qualities that made George C. Marshall a great American military leader and statesman. While Chief of Staff of the Army, Marshall had been concerned about the country’s treatment of Japanese-Americans and had supported the creation of the 442nd Infantry Regiment and its use as a front-line combat unit, believing that a strong record fighting in the nation’s defense would help to reduce postwar racial conflicts. When Colonel Carter brought Peter Kim’s case to him in 1946, Marshall had another opportunity to use his authority to right a historic wrong toward an American of Asian descent. Marshall’s intervention in support of Peter Kim showed that he was a leader ahead of his time, who appreciated the social and political issues that existed in American society and was willing to use the powers of his office to address them when appropriate.

About the Author

Robert Kim is a lawyer and author who recently published Victory in Shanghai: A Korean American Family’s Journey to the CIA and the Army Special Forces, a biographical history of Peter Kim and his brothers James, Richard, and Arthur. He is working on a history of AGAS.