War Department Worry about German Atomic Weapons

From the Archive

In the George C. Marshall papers, there is a box with folders marked “sealed envelope.” These items were not transmitted in a normal fashion, but hand carried to Army Chief of Staff Gen. George Marshall. Much of the correspondence concerned the efforts to build an atomic bomb, not by the United States, but Germany.

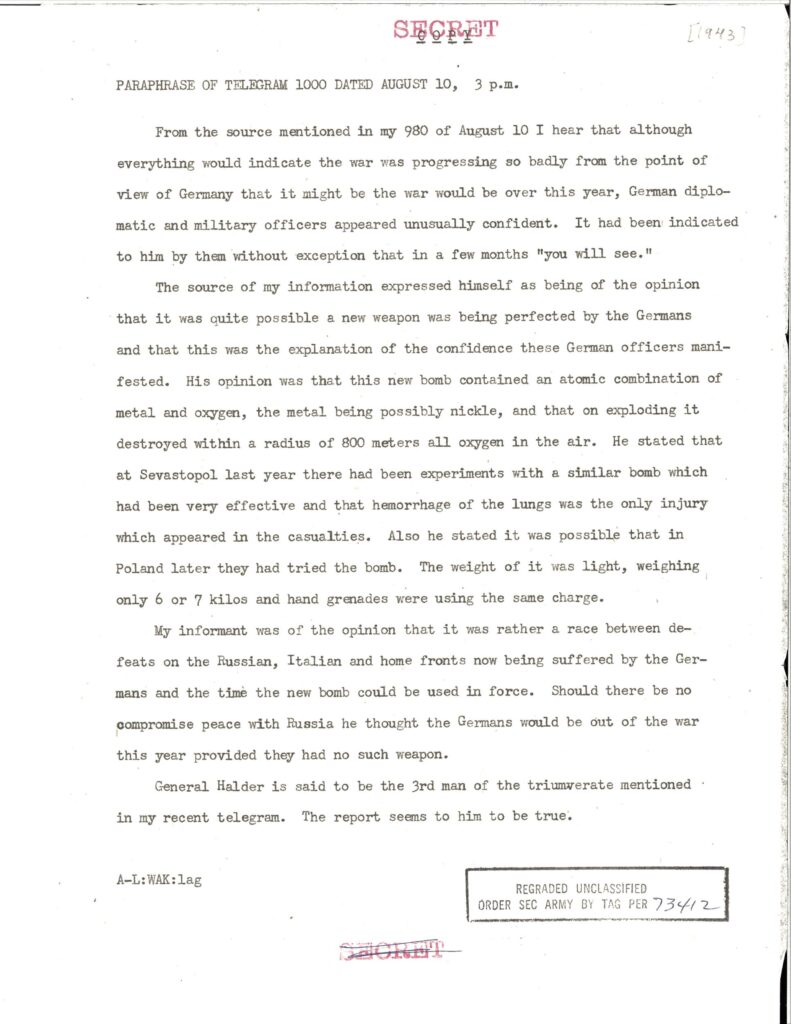

An August 10, 1943 telegram from an unnamed source stated, “it was quite possible that a new weapon was being perfected by the Germans.” This bomb contained “an atomic combination of metal and oxygen … and that on exploding it destroyed within a radius of 800 meters all oxygen in the air.” The informant opined that “defeats … now being suffered by the Germans … the new bomb could be used in force.”

Paraphrase of telegram about German atomic development

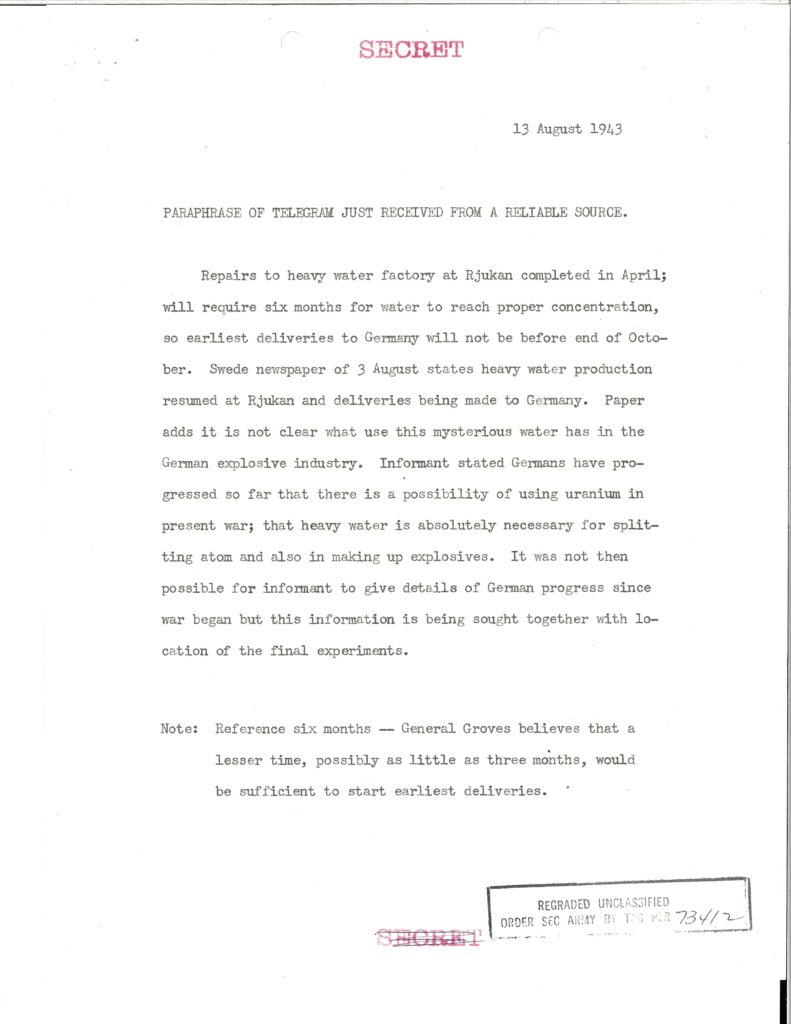

Three days later, another telegram indicated that after a destructive raid the previous February, the heavy water plant (to produce necessary deuterium for this weapon) had been repaired and was again operational. It would be six months “for the water to reach proper concentration, so earliest deliveries to Germany will not be before end of October.” Gen. Leslie Groves, commander of the Manhattan Project, disagreed, with a notation that “a lesser time, probably as little as three months, would be sufficient to start earliest deliveries.”

Paraphrase about the heavy water plant in Norway

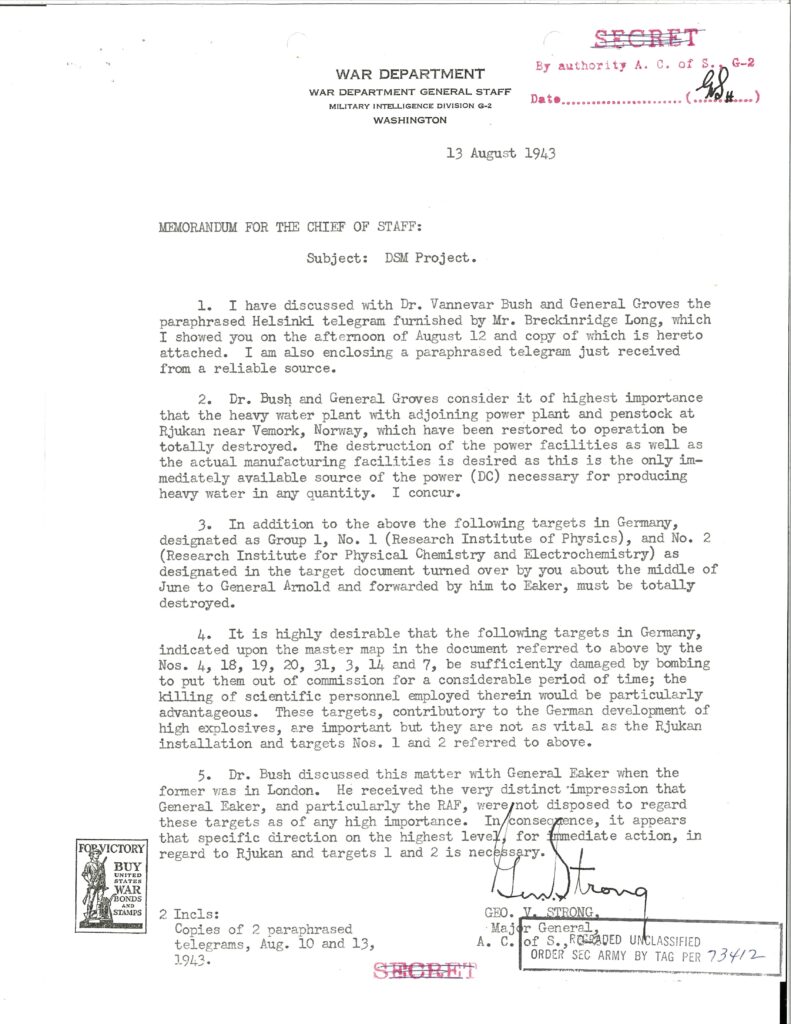

That same day, a plan was laid to prevent Germany from moving forward with their bomb making. The War Department wanted the destruction not only of the heavy water plant, but of the power source to the plant as well. The Royal Air Force and Army Air Forces were tasked with destruction of the Research Institute of Physics and the Research Institute for Chemistry and Electrochemistry in Germany. Other targets listed concerned Germany’s development of high explosives, and that “killing of scientific personnel employed therein would be particularly advantageous.”

Plans for halting German bomb development

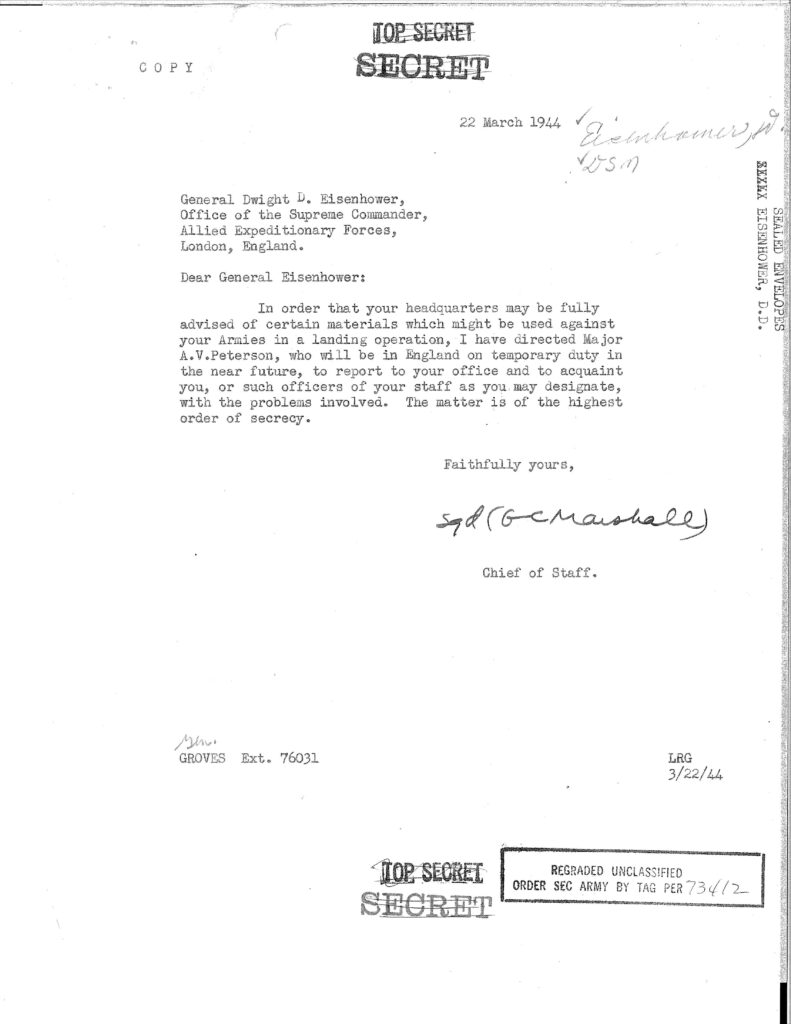

Concern that this new weapon could be used against Allied forces invading Europe, Marshall sent a message to Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower, the Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionary Forces, “that your headquarters may be fully advised of certain materials which might be used against your Armies in a landing operation,” along with an emissary to explain to Eisenhower this information “of the highest order of secrecy.”

Communication to Gen. Eisenhower about the possibility of nuclear exposure to troops.

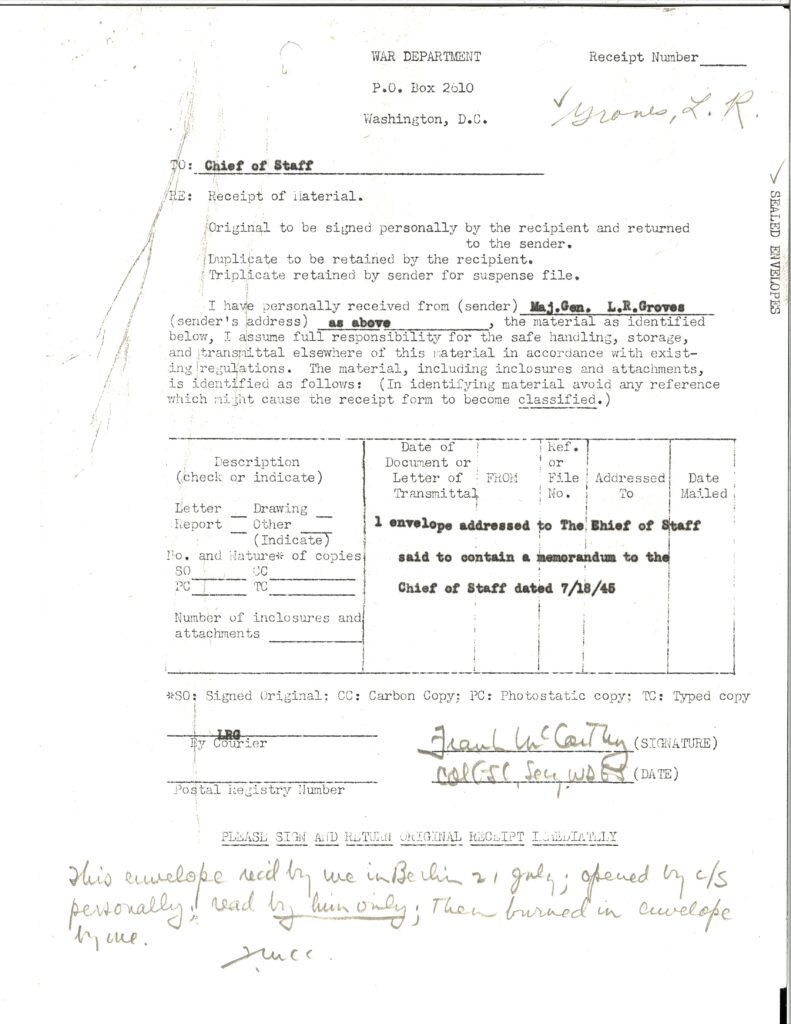

Not all of the messages survived. One items from Groves to Marshall, dated July 18, 1945, was destroyed. Col. Frank McCarthy of the War Department General Staff wrote on one receipt, “read by him only; then burned in envelope by me.” We know what the document was, as Groves kept a copy.

Receipt that shows the message was destroyed after being read by Marshall.

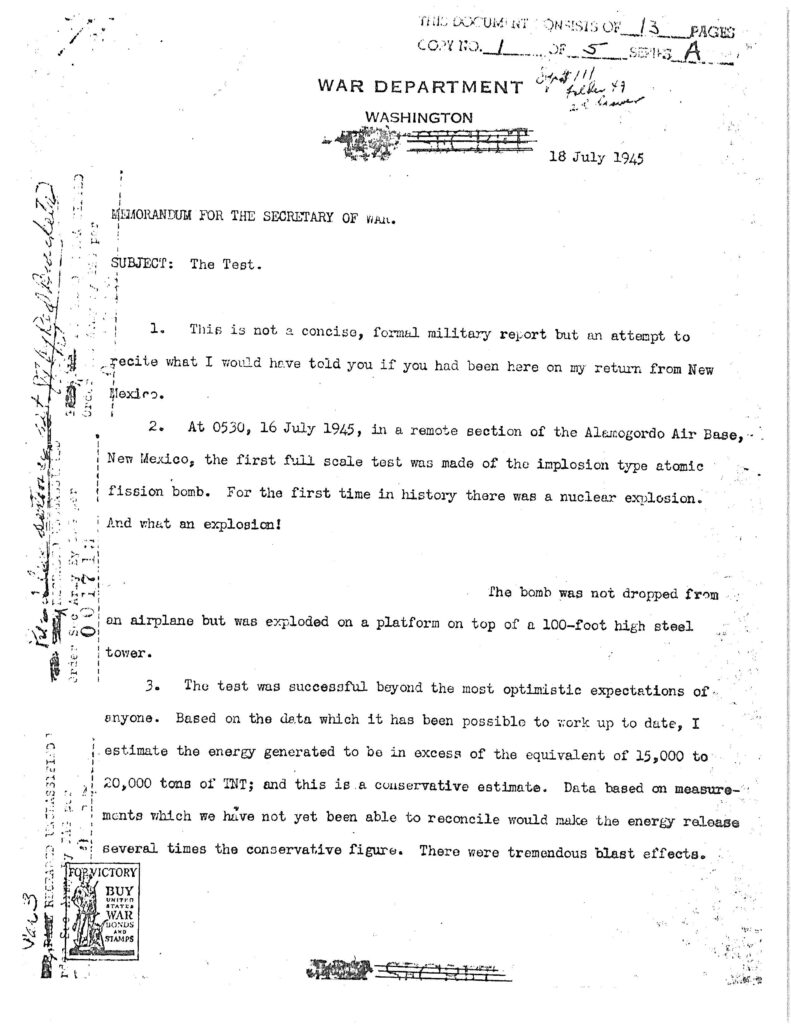

It was the report on “Trinity,” the first atomic bomb explosion, which occurred July 16, 1945.

First page of the “Trinity” report from Gen. Groves

I believe that Marshall may have met Dr. J. Robert Oppenheimer–director of the Los Alamos, N.M., laboratory and in charge of research and development of the bomb–only once, during the awarding of honorary degrees at Harvard University on June 5, 1947, when Marshall made his famous “Marshall Plan” speech.

Honorees at Harvard University, June 5, 1947. Dr. Oppenheimer is front row, far left; and Sec. Marshall is front row, second from left.

Before becoming director of library and archives at the George C. Marshall Foundation, Melissa was an academic librarian specializing in history. She and her husband, John, have three grown children, and live in Rockbridge County with three large rescue dogs. Melissa is known as the happiest librarian in the world! Keep up with her @MelissasLibrary.