A "most valuable and lasting result"

The first wartime meetings of the British and American military chiefs took place in Washington, D.C., just two weeks after Pearl Harbor. The meetings lasted into January with time off for Christmas Day.

One of the most substantive decisions made during these meetings was that there needed to be “post-conference military collaboration in planning, intelligence gathering, troop movements, and materiel priorities and allocations,” and the Combined Chiefs of Staff was created. Prime Minister Churchill later reflected that this was “the most valuable and lasting result” of the conference.

The Combined Chiefs of Staff included the British Joint Staff Mission who represented their military bosses in London, the U.S. service chiefs, and Field Marshal Sir John Dill, Churchill’s representative. Their first meeting was held January 23, 1942.

Gen. George Marshall quickly noticed the cooperation among members representing the military services on British Joint Staff. He realized that the lack of cooperation and communication of the U.S. Joint Board of the services then existing would not allow a united front, so the organization of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, consisting of Marshall, chief of staff of the Army; Admiral Ernest King, chief of Naval Operations; Gen. Henry Arnold, chief of the Army Air Forces; and retired Admiral William Leahy as chairman of the Joint Chiefs gave the American chiefs the same cooperation and communications abilities of the British. The Joint Chiefs held their first meeting in February, and Marshall insisted that although the Army Air Forces were part of the Army, Arnold would have an equal part of the Joint Chiefs. Joint Chiefs meetings were held on Mondays or Tuesdays and frequently involved lunch.

Adm. Ernest King, Gen. George Marshall, Adm. William Leahy, and Gen. Henry Arnold at a Joint Chiefs lunch meeting.

The Combined Chiefs of Staff were to meet weekly. For the first half of 1942, they met Tuesdays at 3 p.m. Meetings were then scheduled for Thursdays, and finally moved to Fridays. Meetings were held in the large conference room of the former Public Health Service building (now part of the Department of the Interior). The Joint Chiefs each had an office in the building; Marshall wanted a “genuine combined command post.” Although the British representatives had offices in their embassy, committees formed by the Combined chiefs used space in the building.

The Public Health building, used by the Combined Chiefs during World War II.

The Combined Chiefs decided how the war would be conducted, including where and when troops and supplies would be allocated. This involved discussion and debate, which sometimes went well, and sometimes not. One of the points of contention was the idea of a Supreme Allied Commander in each wartime theater. Marshall felt that Gen. Douglas MacArthur was the best candidate for the Southwest Pacific, to which Churchill asked what a soldier could know about ships. Marshall responded “What the devil does a naval officer know about handling a tank?”

The Combined Chiefs meeting in the large conference room of the Public Health building, October 1942.

Another long-fought-over issue was whether to plan a cross-channel attack, or continue fighting the war north from the Mediterranean. Churchill wanted his military to continue to take back territory previously held by Britain in the Mediterranean, while the American chiefs preferred to plan an invasion of Europe across the English Channel. Late one evening of a Combined Chiefs meeting in England, Churchill pushed for a delay to the cross-channel attack, and instead wanted to take the island of Rhodes off the coast of Greece. A tired Marshall plainly told the Prime Minister “not one American soldier is going to die on [that] goddamned beach.”

The Combined Chiefs meeting in Quebec, August 1943.

Operations Neptune and Overlord began the invasion of France on June 6, 1944, and the Joint Chiefs left Washington, D.C. on June 8, bound for England. The Combined Chiefs met June 10 and 11, and then boarded ships to cross the English Channel just six days after D-Day. Joined by Churchill, the group had dinner in France on June 12.

The U.S. Chiefs of Staff crossing the English Channel June 12, 1944.

The British Chiefs of Staff, accompanied by Prime Minister Winston Churchill, crossing the English Channel June 12, 1944. Imperial War Museum photo.

During the dinner, Churchill remembered noticing “General Marshall writing industriously, and presently he handed me a message he had written to Admiral Mountbatten, which he suggested we should all sign.”

The message said:

“Today we visited the British and American Armies on the soil of France. We sailed through vast fleets of vessels with landing-craft of many types pouring more and more men, vehicles and stores ashore. We saw artificial harbour in the process of rapid development … we realise that much of the remarkable technique and therefore the success of the venture has its origin in the developments effected by you and your Staff of Combined Operations.”

The U.S. Chiefs of Staff listening and learning in Normandy.

The British Chiefs of Staff and Prime Minister Winston Churchill listen and learn in Normandy. Imperial War Museum photo.

It was an important visit, as Gen. Eisenhower recalled, “Their presence, as they roamed around the areas with every indication of keen satisfaction, was heartening to the troops. The importance of such visits by the high command, including, at times, the highest official of government, can scarcely be overestimated in terms of their value to soldiers’ morale.”

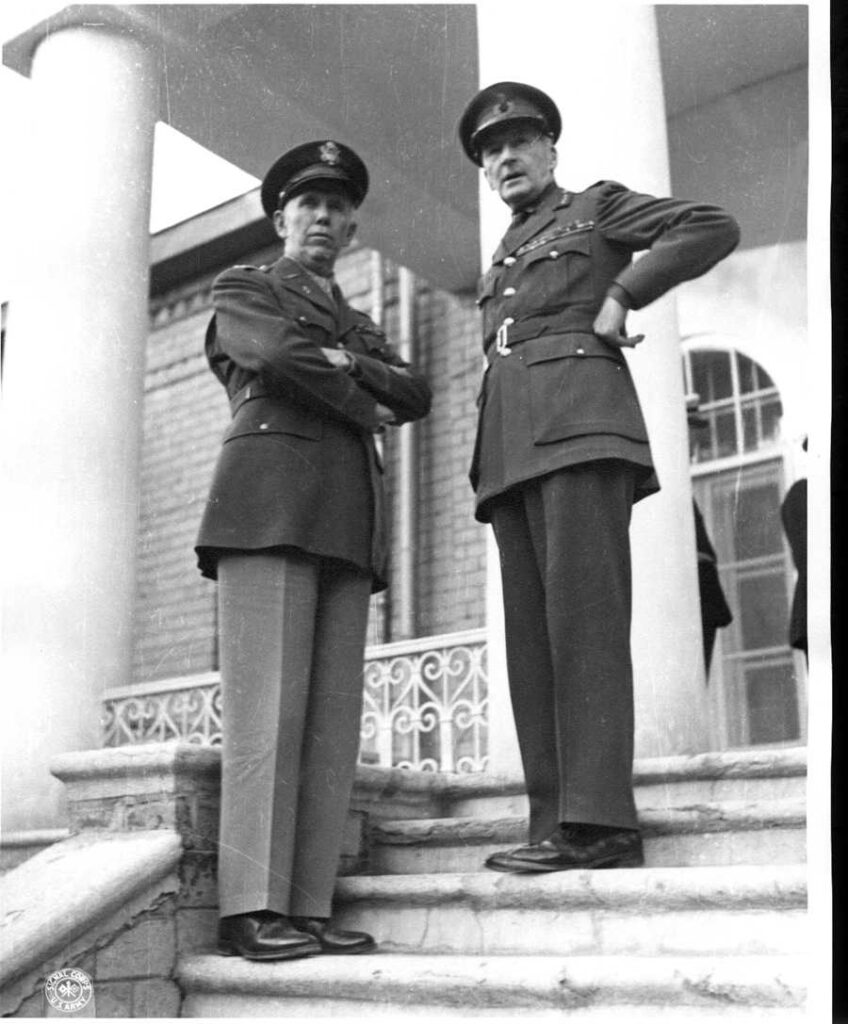

Gen. George Marshall and Field Marshall Sir John Dill in Tehran, November 1943.

Perhaps one of the best things to come from the Combined Chiefs was the close working relationship between Marshall and Dill. As Churchill’s representative, Dill would receive a message from the Prime Minister, and carry it over to Marshall’s office and ask him how they were going to answer it. The relationship of complete trust between the two men meant that Dill frequently explained to the British Chiefs the detailed American point-of-view and to Marshall the British point-of-view, which calmed ruffled feathers and allowed planning to move forward.

Combined Chiefs meeting in Quebec, September 1944.

As the war drew to a close, there was uncertainty in how the Combined Chiefs should move forward, if at all, to secure Europe. France and other countries were clamoring for a seat at the table, and in April 1949, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization eliminated the need for the Combined Chiefs. The cooperation between the militaries of the United States and the United Kingdom has continued, however.

Melissa has been at GCMF since fall 2019, and previously was an academic librarian specializing in history. She and her husband, John, have three grown children, and live in Rockbridge County with two large rescue dogs. Keep up with her @MelissasLibrary.