As told by Gen. Leslie Groves

Gen. Leslie Groves spoke about some of his experiences as the administrator of the World War II atomic science program to Dr. Forrest Pogue in May 1970. His memories shed light on what had been the very secret Manhattan Project. The Marshall Foundation Library also holds Groves’ scrapbook from the project, including his observation of Trinity, the first atomic explosion.

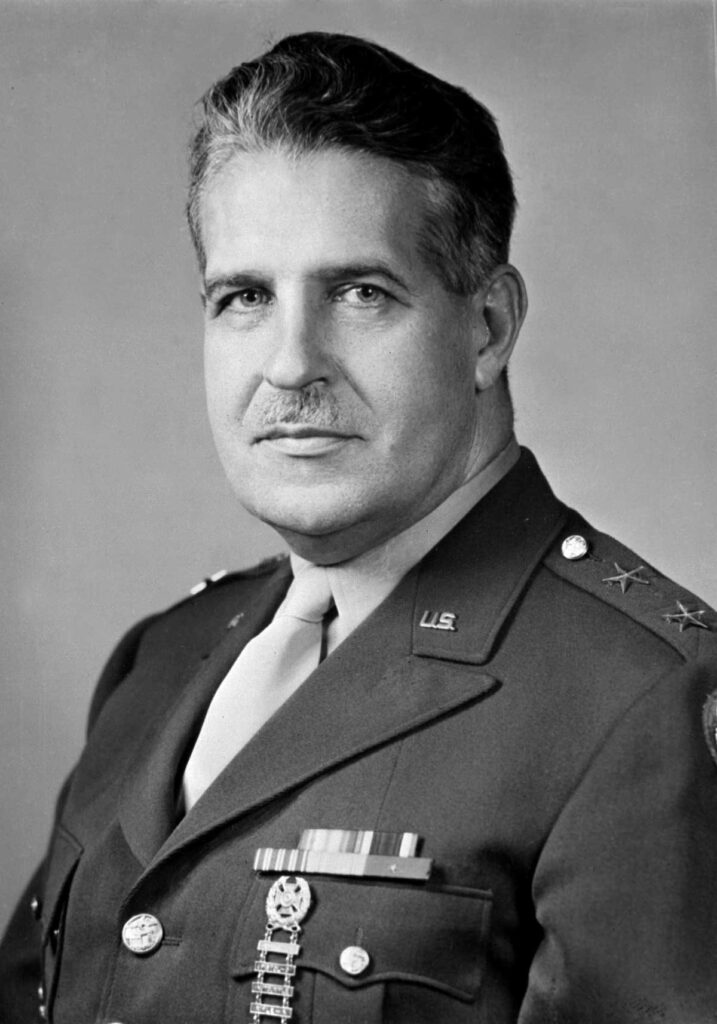

Maj. Gen. Leslie Groves during World War II.

Groves indicated that the research producing nuclear fission was always meant for a bomb to be used during World War II, “From the time that the bomb was first thought of, and Roosevelt was told about it, there was the idea of using it; that there was a chance to use this bomb during the war and that it would be effective.”

The small committee overseeing the project was at first an Army representative, a Navy representative, and a civilian, which was decided at the first meeting. “I was brought into the picture in September of ‘42 … the first meeting involving it which included Secretary Stimson, General Marshall, [Gen.] Somervell, [Gen.] Styer, [Vannevar] Bush, [James] Conant and Admiral Burnell, and Harvey Bundy. I told Stimson that if he wanted to get anything done you could never have a committee of over three people, and I said if you have nine why then I can just assure you that the project will be a failure.”

Those who had a need to know about the project to obtain funding and personnel were not scientists, and Groves told a story about Marshall’s first exposure to the Manhattan Project. “I heard the story about General Marshall saying that after his first meeting on this subject he went home and looked up what he’d written down, all the words he didn’t understand, and looked them up either in the dictionary or encyclopedia and he found that either they didn’t apply or he couldn’t understand what it was all about, and then he decided he had a war to run and he couldn’t become a scientist.”

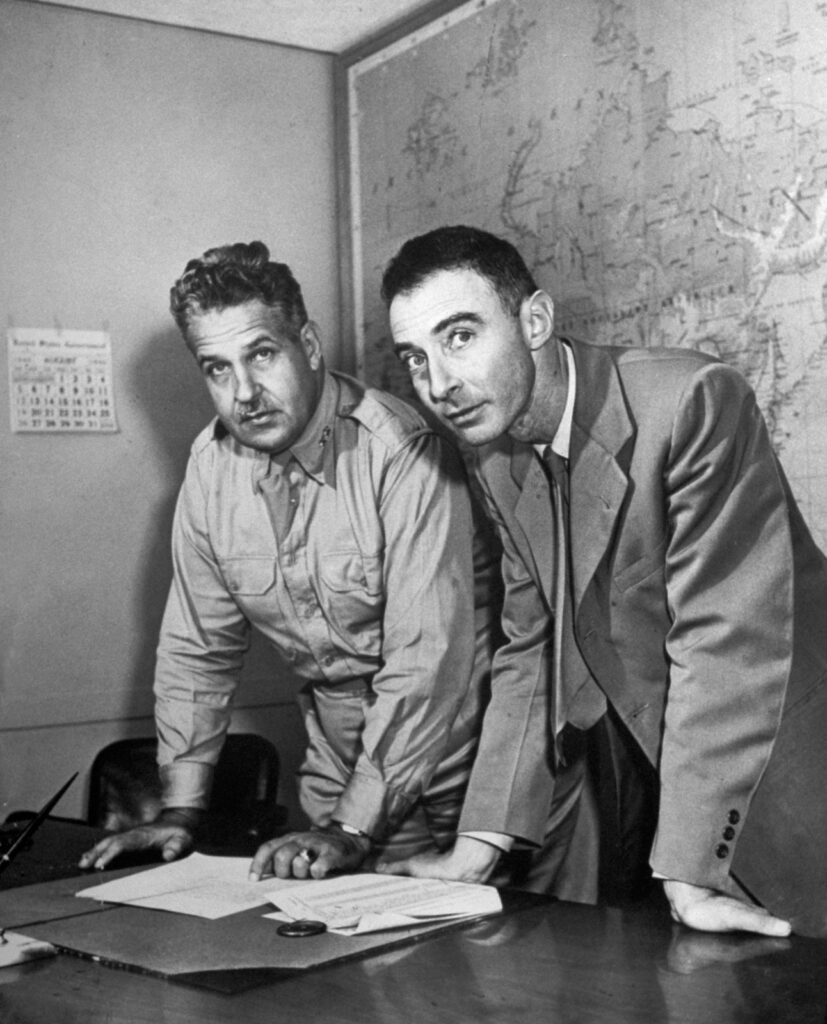

Gen. Groves and J. Robert Oppenheimer, director of the Manhattan Project’s Los Alamos Laboratory.

The Manhattan Project was based largely on theory, and in the beginning, no one was certain which of several options would create fission, or how much it would cost. Groves recalled “that I took a report in to Marshall – I carried it around hand by hand and then turned it over to [Vannevar] Bush to give to the White House. Because it was a report to the President, as I recall, and that’s the one that said that was going to cost on the order of 400 million and that we were going to approach it from several angles and probably one or two of these three proposed methods would prove to be impossible scientifically.”

Groves spoke further on the three methods, “We were talking then of the three – the gas diffusion, the electromagnetic and the plutonium. So that is what the three were. And then that [the report] came back with an okay from FDR. It also had a very strong statement at the end, it was mine completely: we would have to have first priority in men and equipment and materials and if any time this first priority was taken away from us then the project should be abandoned immediately.”

Not everyone who needed to know about the Manhattan Project was in favor of it, either – Adm. William Leahy was not in agreement, as Groves explained, “The Admiral … when I went in to see him … the first time I met him, I took in this report. And he said, ‘I’m awfully sorry to see you tied up with this thing. I speak as an old ordnance expert, and no weapon was ever developed in the war that ever had any effect on the war.’”

Authorities in the United States were not sure how far along the German efforts for a fission bomb had progressed, and whether the Germans would have success first. There was some gallows humor between generals. “I said, well the next time you see him [Marshall], tell him that I’m thinking it might not be a bad idea if we sent some agents into Germany and assassinated a few German scientists. Styer came back and he said, well I asked General Marshall. And I said, what did he say? I was sure he wouldn’t approve it. The remark was quite revealing. He said tell Groves to do his own dirty work.”

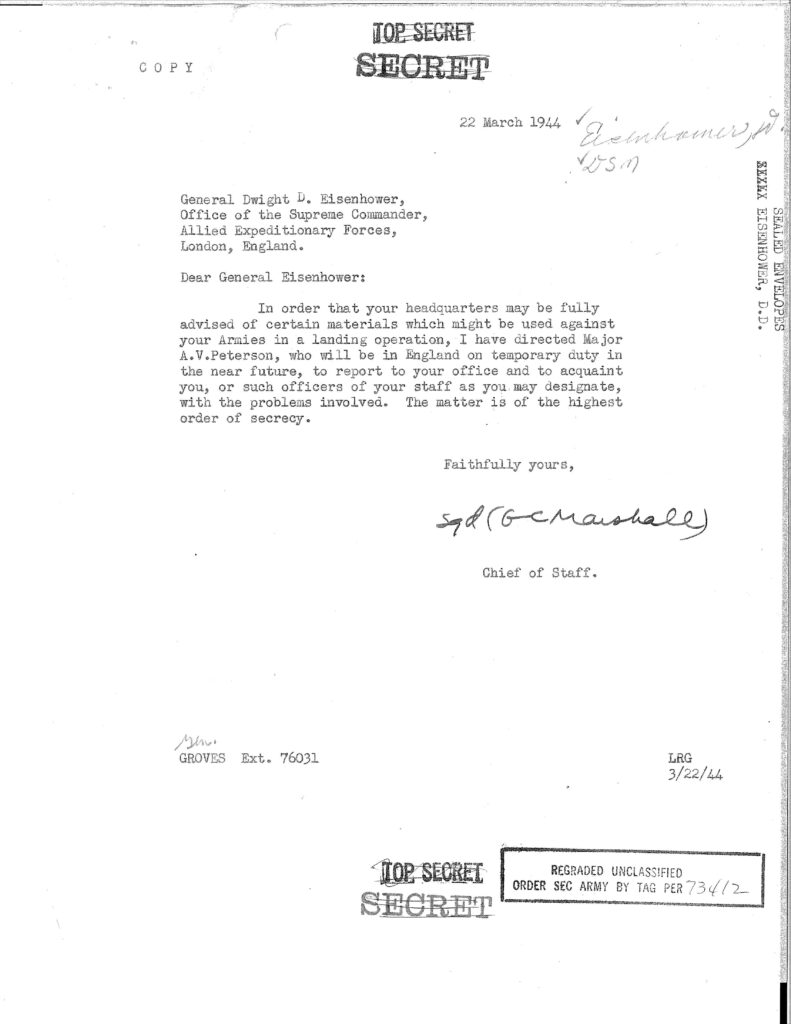

There was also worry about the safety of the allied military participating in the invasion of Europe, and the possibility that radioactive material would be used against them. “He [Marshall] asked me, ‘We’re taking quite a chance, aren’t we?’ And I said, ‘Yes General, we are taking a chance; but I said if we don’t take the chance, you’d better call off the invasion.’ I said, the thing that bothered [me] was I felt the Germans … wouldn’t have used the bomb against us. They would have just taken radioactive waste and … take a road, up all the advancing roads, and just spray it out there.”

Certain materials which might be used against your Armies … the matter is of the highest order of secrecy.

The U.S. military was not certain of the effectiveness of this new weapon, and there were questions whether one or two would be sufficient. Groves wanted to ensure that the Manhattan Project was well-enough funded to continue making atomic bombs if necessary, so he spoke with Marshall about additional money for the program. “I said, ‘I want to ask you a question General as to when you think the war will be over in Japan if the Atomic Bomb is not used? The reason I want to know this is that in case we find we turn up with a very small bomb, small in our terms but still much larger than a blockbuster, we might have to bomb for at least a month or two and particularly on this proposed breakthrough in Kayusu that you’ve told me about.’ And then I said, ‘If that’s the case then I want to expand the facility at Oak Ridge and it’s going to cost a 100 million dollars about, so I don’t want to do it if the war is going to end before July 1, 1946.’ ‘Well,’ he said, ‘it’s going to end before that time.’

Groves wrote up a report on the successful Trinity test, to be shared with Marshall and others attending the Potsdam Conference in Germany.

Twelve seconds into the first atomic explosion.

At 5:30, 16 July 1945, in a remote section of the Alamagordo Air Base, New Mexico, the full-scale test was made of the implosion-type atomic fission bomb. For the first time in history, there was a nuclear explosion. And what an explosion! The test was successful beyond the most optimistic expectations. For a brief period there was a lighting effect, within a radius of 20 miles equal to several suns in midday; a huge ball of fire was formed which lasted for several seconds. This ball mushroomed and rose to a height of over ten thousand feet before it dimmed.

A massive cloud was formed which surged and billowed upward with tremendous power, reaching the substratosphere at an elevation of 41,000 feet, 36,000 feet above the ground, in about five minutes, breaking without interruption through a temperature inversion at 17,000 feet which most of the scientists thought would stop it. Huge concentrations of highly radioactive materials resulted from the fission and were contained in this cloud.

Oppenheimer and Groves at the remainder of the tower which held the first atomic bomb. Atomic Heritage Foundation photo.

After the war, Groves left the commission governing the military involvement with nuclear weapons. He retired in from the Army in 1948.

Before becoming director of library and archives at the George C. Marshall Foundation, Melissa was an academic librarian specializing in history. She and her husband, John, have three grown children, and live in Rockbridge County with two large rescue dogs. Melissa is known as the happiest librarian in the world! Keep up with her @MelissasLibrary.