Several innocent anecdotes Marshall used to tell about his childhood demonstrate his future leadership capabilities. A favorite concerns Marshall’s first “shipping” crisis in about 1888 or so, about the time the U.S. was beginning its great naval expansion.

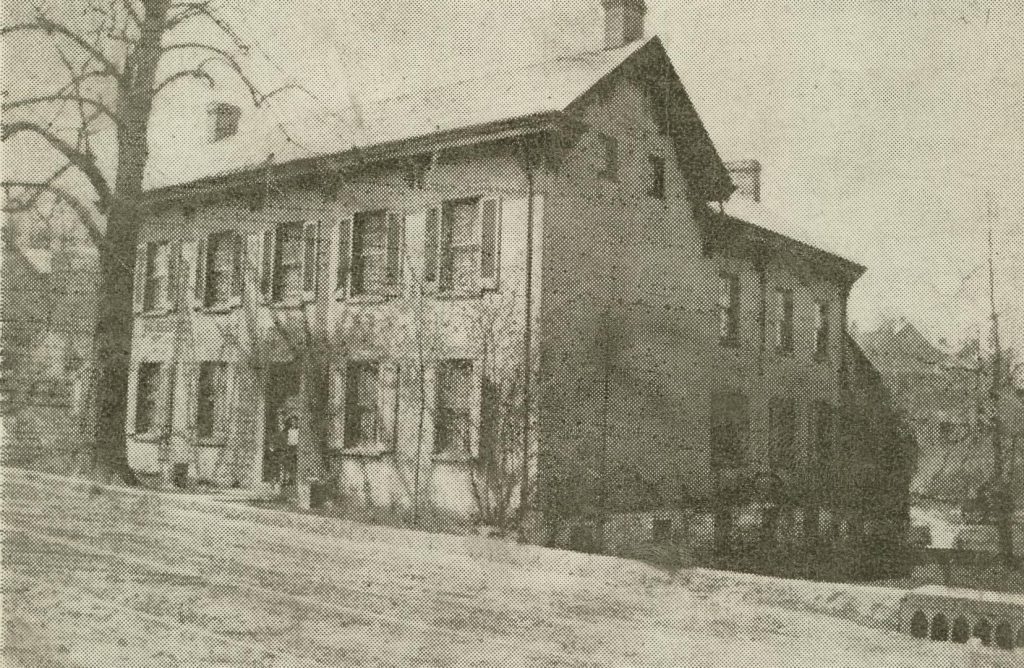

Marshall family home at 130 West Main St, Uniontown, PA, GCMF photo.

Young George and Andrew Thompson had convinced a local carpenter to build them a crude flat-bottomed boat out of scrap lumber. It had a corked hole in the bottom for drainage when it rained. The boys poled their ship around Coal Lick Creek. Incipient service-sector capitalists, they decided to operate a ferry line across the creek for girls after school. Marshall told biographer Forrest C. Pogue the story:

We ran a ferry and had tickets for the ferry. And while the ferry was only the width of the stream yet to us it was a very important crossing. And the girls from school would buy tickets from us with pins and pennies and would come down after school to cross over and back on the ferry. We ran the ferry with great formality.

A section of Coal Lick Run which ran alongside old Marshall property, Uniontown, PA, 1962, GCMF photo.

“My chum would be the engine man and pole it. I don’t remember his costume, particularly, but I know I was the conductor as a rule and I had my mother’s punch from the 500 counting business (that was the card game of the day). I wore my hat backwards, and I took up the tickets.

“One of the incidents of my young life that occurred here and made a definite impression upon me was the girls had gone over to the far bank, and now came the return trip. They had these elaborately prepared tickets that we had made by hand. (We used a typewriter, a rather primitive machine for children of that day). On the return trip the girls got obstreperous and refused to give me the tickets. I was terribly humiliated-with my cap on backwards and my 500 punch machine in my hands to punch the tickets-and what made it worse was my chum Andy began laughing at me. And here I was with the girls in the flatboat all jeering at me and with my engineer and boon companion laughing at me, and I was stuck. Just then my eyes fastened on a cork in the floor of the boat which we utilized in draining it.

“With the inspiration of the moment, I pulled the cork and under the pressure of the weight of the passengers, this stream of water shot up in the air. All the girls screamed and I sank the boat in the middle of the stream. And they all had to wade ashore and promised me what there fathers were going to do to me. I never forgot that because I had to do something and I had to think quickly, and what I did set me up again as the temporary master of the situation. Our boat sank in the middle of the stream and we had to get it ashore later on.”

Marshall had lost control of the situation and he had to act quickly to regain it and to punish the rule breakers. He recognized that verbal or physical abuse of the girls would lead to later, greater trouble from higher (parental) authority, and also that, given the social; and cultural milieu of the time, such a response by him would result in unacceptable public, ‘political,’ and media reactions. His response, then, had to be swift and within narrow constraints.

They had been punished within the parameters of the game, and if they protested to higher authority, they would incriminate themselves. Although at some cost to himself, Marshall had mastered the crisis. The transgressors were probably more careful in dealing with him henceforth.

A section of Coal Lick Run which ran alongside old Marshall property, Uniontown, PA, 1962, GCMF photo.