It was first called the “Laboratory for the Development of Substitute Materials,” then the “Manhattan Engineer District,” after the location of offices in New York City near the Army Corps of Engineers offices.

The project was very secret – the small committee running it included Vice President Henry Wallace, Secretary of War Henry Stimson, Army Chief of Staff George Marshall, chemist Dr. James B. Conant, engineer Dr. Vannevar Bush, Maj. Gen. Leslie Groves and a couple more. It was so secret that for a while, information was not even shared with British Prime Minister Churchill.

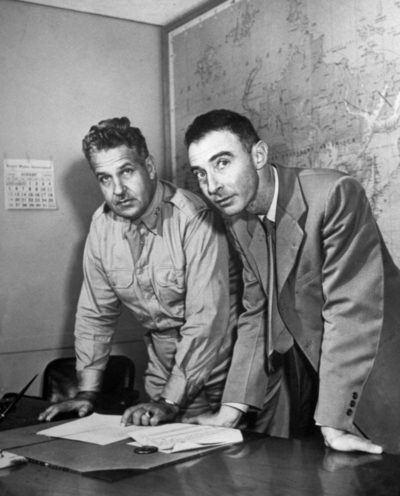

The project stemmed from the information that the Germans had a nuclear weapons program, so the United States gathered scientists and technicians, led by Maj. Gen. Groves (who had just completed the building of the Pentagon) to Hanford, WA: Oak Ridge, TN; Chicago, IL; and Los Alamos, N.M., to ensure that the United States developed a weapon first. The engineering of such a weapon took place at Los Alamos, guided by theoretical physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer.

Maj. Gen. Leslie Groves and J. Robert Oppenheimer

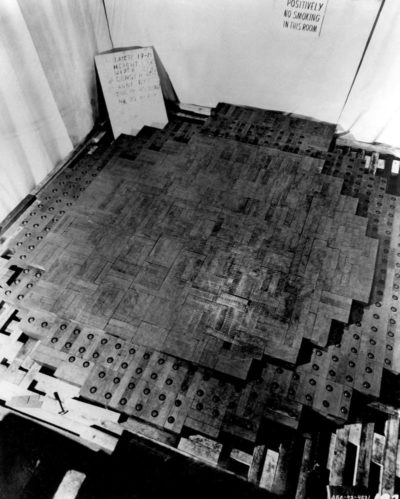

Scientists’ theories became experiments, and one of the most promising was the famous 1942 attempt at fusion under the bleachers at Stagg Field at University of Chicago. The first self-sustaining nuclear chain reaction took place in an experimental reactor made of graphite blocks called Pile-1, and proved the theory of exothermic nuclear fission would work.

Graphite bars in Pile-1 at the University of Chicago (Atomic Archive photo)

One of those graphite bars from Pile-1 is at George C. Marshall Foundation, courtesy of the John A. Adams ’71 Center of Military History and Strategic Analysis.

Library and Archives Director Melissa Davis holding one of the graphite bars from Pile-1.

Uranium-235 is the only naturally occurring fissile isotope, but it makes up a small percentage of the uranium mined, so the uranium-235 was separated out in the factory at Oak Ridge, TN, and shipped to scientists in Los Alamos, N.M., by rail, in nickel containers inside briefcases, accompanied by Army officers dressed as salesman.

There was only enough weapons-grade uranium-235 for one bomb, and the scientists and engineers were confident that the gun-type weapon, where the reaction was begun by the “shot” of a mass of uranium-235 into more uranium-235, would work. This bomb, called “Little Boy” was on its way to California for use overseas without being tested.

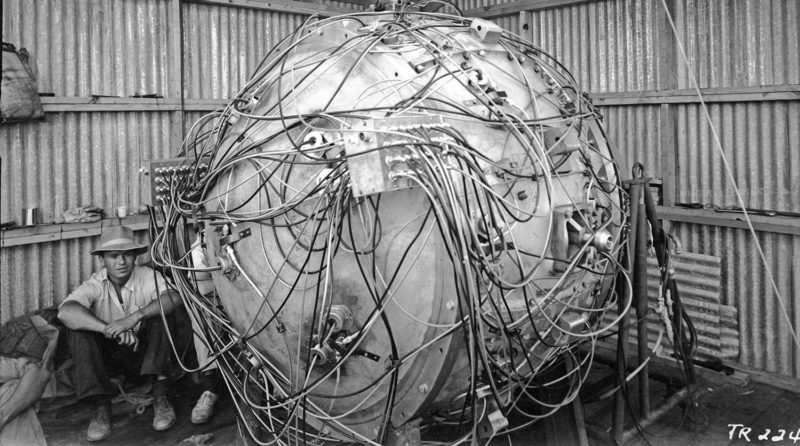

The first nuclear device tested, nicknamed “Gadget,” had a solid 35-pound plutonium core, and used an implosion to initiate the nuclear fission reaction, which was a novel theory. It was determined that the implosion bomb needed to be tested, and that information about nuclear explosions in general should be gathered. The attempt to explode Gadget in a test named “Trinity” by Oppenheimer after a John Donne poem, was scheduled.

The Gadget (Atomic Heritage Organization photo)

Tower for Gadget (Atomic Heritage Organization photo)

A half hour before sunrise on July 16, 1945, in Bingham, N.M, Gadget was dropped from a 100-foot steel tower.

Gadget at 12 seconds post-explosion. Atomic Archive photo.

“The whole country was lighted by a searing light with the intensity many times that of the midday sun. It was golden, purple, violet, gray and blue. Thirty seconds after the explosion … the strong, sustained awesome roar which warned of doomsday and made us feel that we puny things were blasphemous to dare tamper with the forces heretofore reserved to The Almighty.” Brig. Gen. Thomas F. Farrell, in Groves’ July 18 report to Secretary Stimson.

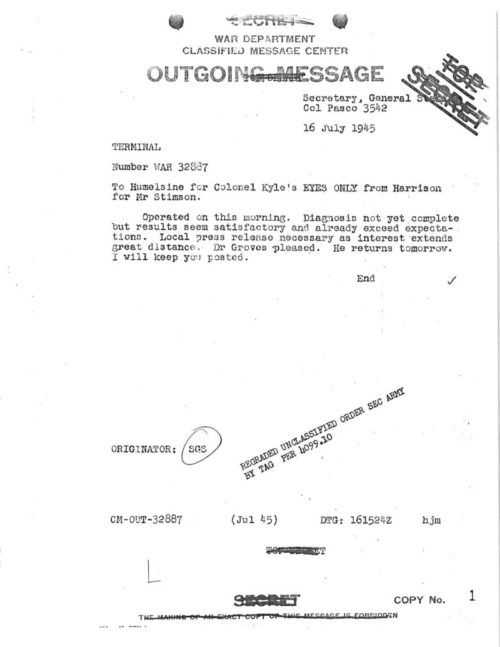

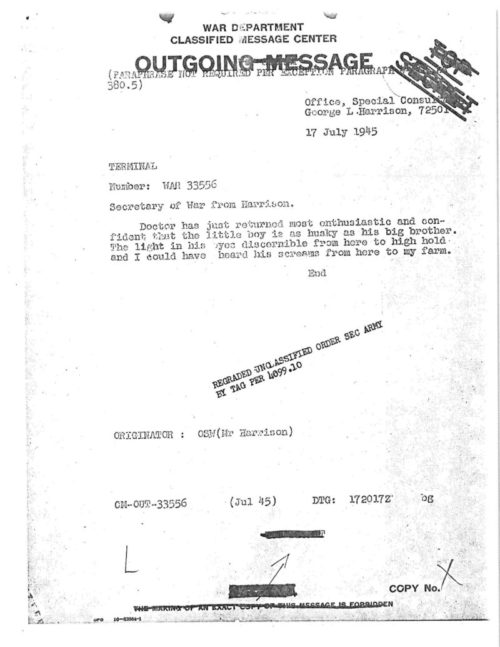

Two cleverly worded messages were sent to Secretary Stimson on July 16 and 17:

In his July 18, 1945, report to Secretary Stimson, Groves reported that “a lighting effect within a radius of 20 miles equal to several suns in midday. A massive cloud was formed which surged and billowed upward with tremendous power, reaching the substratosphere at an elevation of 41,000 feet.” He also reported that the “steel from the tower was evaporated.”

The power of the explosion left another tower built of 40 tons of steel one half mile from the explosion ripped from its foundation and torn apart. Groves commented that “I no longer consider the Pentagon a safe shelter from such a bomb.”

J. Robert Oppenheimer and Maj. Gen. Leslie Groves at the Trinity site September 1945. Groves is shown wearing shoe coverings to prevent carrying radioactive material. (Atomic Archive photo)

The sand in the blast area melted and mixed with the radioactivity of the bomb, forming light green glass called trinitite. In 1958, Capt. Joseph Spivey was stationed in the area, attached to a Nike missile training site. Soldiers who worked for him visited the Trinity bomb site, and brought him back some trinitite, which he donated to George C. Marshall Foundation:

Our trinitite measures about one inch by one inch.

Although the test of the first nuclear explosion was a success, Groves closed his report to Secretary Stimson, “we are all full conscious that our real goal is still before us.”

On Aug. 6, 1945, the uranium bomb “Little Boy” was dropped on Hiroshima, Japan. The secret was out, and the nuclear age was born.

Notes:

Photos and material for this blog from George C. Marshall Foundation unless otherwise noted.

Melissa has been at GCMF since 2019, and previously was an academic librarian specializing in history. She and her husband, John, have three grown children, and live in Rockbridge County with three large rescue dogs. Keep up with her @MelissasLibrary.