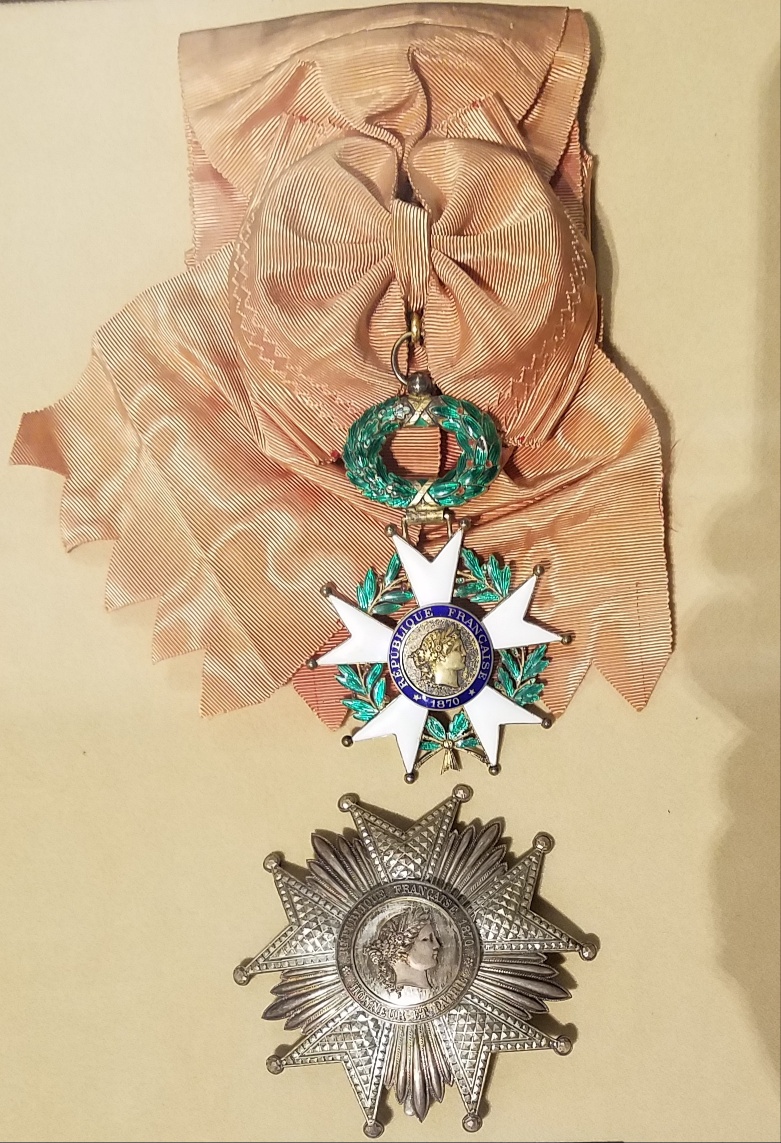

In 1919, Lt. Col. George C. Marshall, Jr. was awarded the Ordre National de la Légion d’honneur Officier (National Order of the Legion of Honor, degree of officer), for his service in France during World War I. On this day seventy-three years ago, after World War II had ended in Europe, he was promoted to the order’s highest degree of Grand-croix (Grand Cross), at the French Embassy in Washington, D.C.

The Ordre National de la Légion d’honneur order of merit was established by Napoleon Bonaparte on May 19, 1802 and has five degrees:

• Chevalier (Knight) : minimum 20 years of public service or 25 years of professional activity with “eminent merits”

• Chevalier (Knight) : minimum 20 years of public service or 25 years of professional activity with “eminent merits”

• Officier (Officer) : minimum 8 years in the rank of Chevalier

• Commandeur (Commander) : minimum 5 years in the rank of Officier

• Grand-officier (Grand Officer) : minimum 3 years in the rank of Commandeur

• Grand-croix (Grand Cross) : minimum 3 years in the rank of Grand-officier

Napoleon set up a merit-based system of award for soldiers and civilians that was not based on nobility or aristocratic ties. Both men and women, French-born or not, could earn the Ordre National de la Légion d’honneur.

Defending the awarding of medals, Napoleon once declared:

“You call these baubles, well, it is with baubles that men are led… Do you think that you would be able to make men fight by reasoning? Never. That is good only for the scholar in his study. The soldier needs glory, distinctions, rewards.”

General George C. Marshall, in his lifelong study of military history, may have read this quote by Napoleon, and also stressed the importance of recognizing valor and honor, though in a much different tone than Napoleon. He made certain men were awarded medals for their endeavors because he knew it boosted morale. In February 1944, he defended this view when President Roosevelt asked for a “more definite policy in regard to all medals, citations and decorations. There is always a danger we will cheapen the value of such things if we hand out too many of them.”

Marshall responded by writing a memorandum to President Roosevelt that explained the importance of prompt battlefield recognition: “The Victory medal with its bronze and silver stars was authorized too late to have any effect on the efficiency of the Army. I received a ribbon for service in Germany twenty-three years after I returned to the United States.” He asked Roosevelt to “Permit these young men who are suffering the hardships and casualties to enjoy their ribbons, which mean so much to them, in uniform. They cannot wear them once they return to civilian attire.”

A collection of Marshall’s World War I and World War II medals, including those mentioned above, are on display at the Marshall Museum, open Tuesday through Saturday, 11am-4pm.

—-

[1] Antoine Claire Thibaudeau (1827). Mémoires sur le Consulat. 1799 à 1804. Paris: Chez Ponthieu et Cie. pp. 83–84.

[2] Roosevelt Memorandum for the Secretary of War and the Secretary of the Navy, January 11, 1944, GCMRL/G. C. Marshall Papers [Pentagon Office, Selected].